Dr Thomas Dixon is Director of the Centre for the History of the Emotions at Queen Mary, University of London.

In my previous post on this blog I wrote about Oscar Wilde’s famous courtroom defence of the ‘love that dare not speak his name’. Whatever its exact meaning, Wilde’s speech aroused strong feelings in its hearers. It is recorded that it was greeted with some applause, mingled with hisses, from the public gallery, at which the judge was moved to exclaim:

If there is the slightest manifestation of feeling I shall have the Court cleared. There must be complete silence preserved.

This is a wonderfully Victorian judicial pronouncement, and I am interested by what it implies about feeling, as a threatening and unseen force, the manifestation of which could disrupt the proper, silent operation of justice. When the jury could not reach a conclusion in the first Wilde trial, there was a retrial. Again there were outbursts from the public gallery, to which the judge again reacted vigorously:

These interruptions are offensive to me beyond anything that can be described. To have to try a case of this kind, to keep the scales even and do one’s duty is hard enough; but to be pestered with the applause or expressions of feeling of senseless people who have no business to be here at all except for the gratification of morbid curiosity, is too much.

The gratification of morbid passions, like the manifestation of excited feelings, was not a proper activity for a Victorian courtroom. But these were not the only ways that feelings and passions made their way into the legal arena (I have written in the Journal of Victorian Culture, for instance, about the tears of judges and others in Victorian courtrooms).

In the same month that the Wilde scandal was unfolding in the Central Criminal Court, another, less remembered sex scandal was being played out a ten-minute walk away in the Divorce Court, within the recently opened Royal Courts of Justice on the Strand.

The matter at hand had similarities with the Wilde case – a prominent member of high society being accused of ‘abominable’ and ‘unnatural’ crimes. While Wilde’s principal accuser had been the Marquess of Queensberry, the accuser of Earl Russell – grandson of the erstwhile Prime Minister, and elder brother of the philosopher Bertrand Russell – was his own wife, Countess Russell – previously Mabel Edith Scott, who made her living by singing on the variety stage.

The matter at hand had similarities with the Wilde case – a prominent member of high society being accused of ‘abominable’ and ‘unnatural’ crimes. While Wilde’s principal accuser had been the Marquess of Queensberry, the accuser of Earl Russell – grandson of the erstwhile Prime Minister, and elder brother of the philosopher Bertrand Russell – was his own wife, Countess Russell – previously Mabel Edith Scott, who made her living by singing on the variety stage.

The Countess repeatedly and publicly alleged that her husband had engaged in ‘unnatural’ crimes with a certain Mr Roberts. When Earl Russell sued for divorce in 1895 it was on the grounds that these allegations amounted to an act of cruelty by his wife against him. Since 1858 there had been a jury in such cases and in this case they found in favour of the Earl. The allegations made by the Countess (and her mother), the jury thought, were clearly the worst kind of cruelty.

The Countess repeatedly and publicly alleged that her husband had engaged in ‘unnatural’ crimes with a certain Mr Roberts. When Earl Russell sued for divorce in 1895 it was on the grounds that these allegations amounted to an act of cruelty by his wife against him. Since 1858 there had been a jury in such cases and in this case they found in favour of the Earl. The allegations made by the Countess (and her mother), the jury thought, were clearly the worst kind of cruelty.

The Court of Appeal and the House of Lords disagreed, however, and to understand why we need briefly to look at the way that the legal concept of ‘cruelty’, as used in divorce cases, had developed during the previous hundred years.

The Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857 transferred matrimonial cases from ecclesiastical to civil jurisdiction.The newly created secular Divorce Court inherited the rules and principles that had governed the ecclesiastical court prior to that date. And by far the most frequently cited precedent, in cases involving the allegation of cruelty, was the judgement delivered by Lord Stowell in 1790 in the case of Evans v. Evans.

The key tenet was that cruelty must have a bodily aspect – it must give rise to injury to ‘life, limb, or health’ or to reasonable fear of such bodily injury. Lord Stowell explicitly excluded hurt feelings from the category of cruelty:

The key tenet was that cruelty must have a bodily aspect – it must give rise to injury to ‘life, limb, or health’ or to reasonable fear of such bodily injury. Lord Stowell explicitly excluded hurt feelings from the category of cruelty:

What merely wounds the mental feelings is in few cases to be admitted, where it is not accompanied with bodily injury, either actual or menaced. Mere austerity of temper, petulance of manners, rudeness of language, a want of civil attention and accommodation, even occasional sallies of passion, if they do not threaten bodily harm, do not amount to legal cruelty.

Stowell’s view was that those who had made an ‘injudicious connection’, no matter how unhappy their married lives, should ‘suffer in silence’ unless they were in imminent physical danger. As in the judicial responses to the public gallery in the Wilde trials, feelings were to be kept silent:

Everybody must feel a wish to sever those who wish to live separate from each other, who cannot live together with any degree of harmony, and consequently with any degree of happiness, but my situation does not allow me to indulge feelings, much less the first feelings of an individual; the law has said that married persons shall not be legally separated on the mere disinclination of one or both to cohabit together.

During the first decades of the secular Divorce Court’s existence, this principle that separations should be granted to protect the body rather than the feelings was frequently reiterated.However, there were occasional cases that suggested the exclusion of injury to the feelings was not absolute. These fell into two categories.

First, from time to time judges seemed to concern themselves with the impact of the respondent’s conduct on the feelings of the petitioner – especially when that conduct was an outrage to the feelings of a respectable person – for instance in cases where a husband spat in his wife’s face, or treated her in public like a common prostitute, or placed her own domestic servants in a position of authority over her. Countess Russell’s allegation that her husband had engaged in ‘unnatural practices’ was another such case where any respectable person’s feelings would be outraged.

The second kind of case where the petitioner’s emotional state was invoked involved medical evidence. In Stowell’s landmark judgement, he had referred to harm to ‘life, limb, or health’. The case of Kelly v. Kelly in 1869 – involving a tyrannical clergyman’s mistreatment of his wife – seemed to establish the principle that harm to mental health as well as harm to bodily health could qualify as cruelty. This meant not only that nervous disorders brought on by psychological cruelty could be considered grounds for divorce, but also that medical experts were of increasing importance, in determining whether the petitioner’s mental and physical health had truly been damaged.

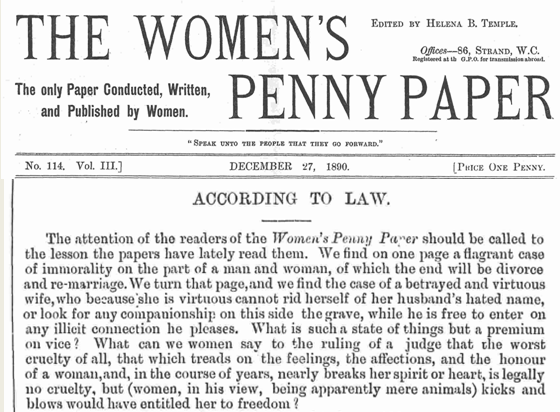

Despite this move away from a purely physical definition of cruelty, there was still resentment among Victorian feminists about the dominant legal interpretation of ‘cruelty’, as is evident in the editorial pictured below from The Women’s Penny Paper in 1890.

The decision of the Court of Appeal in the Russell case, reaffirmed by the House of Lords, seemed to change things only a little. It reinforced both the Stowell principle that mere injury to feelings was no ground for divorce, and also the suggestion that it was injury to health that must be proved – something that Earl Russell’s lawyers had not even attempted to establish.

The decision of the Court of Appeal in the Russell case, reaffirmed by the House of Lords, seemed to change things only a little. It reinforced both the Stowell principle that mere injury to feelings was no ground for divorce, and also the suggestion that it was injury to health that must be proved – something that Earl Russell’s lawyers had not even attempted to establish.

However, the category of ‘cruelty’ had in fact expanded considerably since 1790. The discussions in the House of Lords on the Russell case in 1897 made explicit what had already been hinted at by earlier judgements – that any behaviour that even led to a reasonable apprehension of injury to mental health could be considered legal cruelty. That was a broad definition that left plenty of room for judicial discretion in offering protection to the feelings as well as the body of the petitioner.

The survey of Victorian divorce cases I have undertaken so far has encouraged me to think about ways that official ideologies – official regimes of emotion – have come into contact with, and tried to classify and control, the feelings associated with everyday life in general and with marital relations in particular.

The whole process can be seen – as revealed in the comment of the judges in the Wilde trials with which I started – as an attempt to eliminate, whether by punishment, repression or medicine, troublesome and unwanted feelings.

In a typical divorce case there were three sets of unwanted feelings to deal with. First, there were the respondent’s passions – dangerous monsters, unleashed on the body or mind of the petitioner. A typical case would involve violence and authoritarian control, often exacerbated by drink, which had the effect of strengthening the passions and weakening the will.

Then there were the feelings of the petitioner, which may have become excited, strained or outraged by the cruelty of the respondent and which, like vulnerable and innocent children, needed to be protected by the Court.

Finally, in the emotional triangulation of the Divorce Court, there were the feelings of the judge and the jury. These were particularly problematic – like suggestible and muddle-headed theatre-goers who were too easily swayed by the performance.

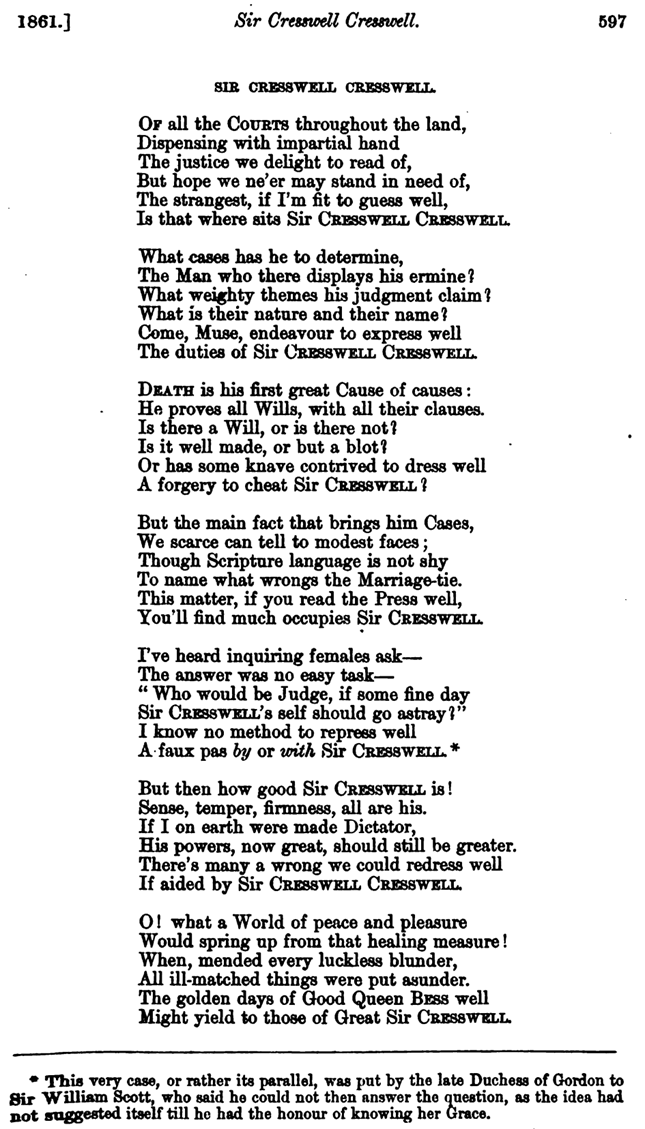

In the first case in which a jury was asked to decide on questions of cruelty, in May 1858, the judge, the magnificently named Sir Cresswell Cresswell, reflected that previously:

the judges, who have had the sole determination of such questions, used to take the papers home and read them there, and if the first perusal unavoidably excited feelings of indignation on one side or the other, they had ample time for a calm re-consideration.

Now that juries found themselves in a similar position, Cresswell continued, they must ‘not allow themselves to be carried away with feelings of partiality, which may have been excited.’ Instead the jury must be ‘calm and cautious’ in their deliberations. Sir Cresswell Cresswell’s pioneering work in the new secular divorce court was marked by a poem in Blackwood’s Magazine in 1861, including the lines ‘There’s many a wrong we could redress well, If aided by Sir Cresswell Cresswell.’

In the case in May 1858, the jury found in favour of the beaten wife and against her husband who was ‘a very ill-tempered person, who was in the habit of knocking her about when he was in a passion.’ The verdict in this historic case was met with applause from the public gallery to which Creswell responded by saying he ‘could not tolerate such a manifestation of feeling in a court of justice.’

In the case in May 1858, the jury found in favour of the beaten wife and against her husband who was ‘a very ill-tempered person, who was in the habit of knocking her about when he was in a passion.’ The verdict in this historic case was met with applause from the public gallery to which Creswell responded by saying he ‘could not tolerate such a manifestation of feeling in a court of justice.’

And in 1912, when a Royal Commission started the process which would ultimately lead to reforms to the divorce laws, again it was ‘feelings’ that were blamed. The former President of the Divorce Court, Sir John Bigham, spoke about the difficulty of persuading juries to act in accordance with the ‘injury’ definition reaffirmed in the Russell case. Bigham told the Royal Commission:

when once you get a question in the hands of a jury you do not know what is going to happen. They disregard all directions and give their verdict (probably quite rightly) according to their feelings.

Bigham later made similar remarks about juries in divorce cases brought by wives petitioning on the grounds of adultery: ‘Their feelings are always in favour of the lady – always.’

Whether in the domestic arena, in the public gallery, or even in the jury room, the task seemed to be to prevent the tangible, physical manifestation of these powerful but invisible psychic forces, the ‘feelings’.