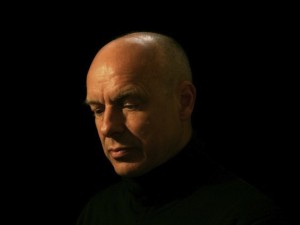

I’m sitting in the West London studio of Brian Eno, one of the all-time great pioneers of sound recording, and my dictaphone has broken. Right at the beginning of our interview. ‘It’s…er…saying it’s full’, I say. ‘How do I delete files?’ ‘Let me have a look’, says Eno. ‘Hmmm. I think you need to delete them on a computer’. ‘OK, don’t worry’, I say, glancing at the clock in the knowledge I only have an hour for our interview. ‘I’ll just scribble while you talk.’ Then my pen runs out.

I’m sitting in the West London studio of Brian Eno, one of the all-time great pioneers of sound recording, and my dictaphone has broken. Right at the beginning of our interview. ‘It’s…er…saying it’s full’, I say. ‘How do I delete files?’ ‘Let me have a look’, says Eno. ‘Hmmm. I think you need to delete them on a computer’. ‘OK, don’t worry’, I say, glancing at the clock in the knowledge I only have an hour for our interview. ‘I’ll just scribble while you talk.’ Then my pen runs out.

Eno starts to get the giggles and I have to sigh and shrug. My moment of rock glam has quickly descended into farce. Never mind – we are here, after all, to talk about learning to let go and surrender to the flow. Eno has been thinking about the concept of surrender in art for decades, and in the last few years he’s started to articulate his ideas. As someone researching (and searching for) ecstasy, I’m fascinated by his thinking on the subject. So, scribbling furiously with a pen he has kindly leant me, I ask him to explain what he means by surrender.

Eno: I started noting that I liked certain kinds of experience, different from rock & roll experiences – more contemplative, calm and reflective. When I started making ambient music [he invented the genre ‘ambient’ in the mid-1970s after leaving Roxy Music], all the critics could see was what’s missing – a beat, lyrics, chord changes, everything they considered music. And it’s true, I had stripped out a lot of what constitutes music. I didn’t want it to be stimulating, I wanted the opposite. But I didn’t yet have the word surrender. I just knew I wanted something that induced calm, which put me out of the loop in terms of pop in the late-1970s.

Here’s an Eno ambient song called Going Unconscious. The words are ‘Going Unconscious / Trembling / With eyes open / I see you / Surrender’.

Over the years, I carried on refining the idea and refining the music, and wondering what class of experience this belongs to. I noticed people seemed to experience it through my art. People would write in the visitors books for my light works, things like ‘I wish this was what church was like’ or ‘I’ve never felt so calm’.

But the thing that really got me thinking about surrender was when I saw an art critic bustle in to the gallery [he gets up and imitates the critic bustling in], and staring at the art impatiently, looking like he was about to leave, and then the lights changed very slightly, and he stood there, then moved closer to a chair, then sat down on the chair, and eventually he was totally absorbed in the art work. And I thought, this person is surrendering. He’s letting something happen and stopping being in control.

So that made me think about not being in control. We usually think that humans’ success comes from being in control, from science, craft, technology. Learning to control and master our environment is an important part of what we are. But if you think of the evolutionary history of humans, until very recently, we weren’t much in control of anything. Humans were at the mercy of forces that were completely beyond our control – the elements, wild animals, plagues, floods and so forth. Life was unpredictable, basically. In that sort of environment, control was useless as a response. So, for a lot of human history, there’s an acknowledgement that you have to go with the flow, not fight it. The best strategy is to navigate and position yourself within the flux of circumstances.

Here’s a clip of Eno talking about surrender in art and religion:

And we’ve learnt not just to accept being out of control, but to enjoy it.

Yes, and to be good at it. I think surrender should be an active verb. We think of it as passive. I’m interested in the words active and passive – what if you think of it as action and passion. In other words, surrender is an active choice.

Right. The musicologist James Kennaway makes a similar point about Beatlemania – people were very worried about teenage girls screaming away and losing control, but, as he suggests, really those girls were making a choice to surrender, to go with it and have fun losing control.

I find the metaphor of surfing useful. Surfers take control of the wave, then they’re carried by it, then they take control, then they’re carried. That’s what you’re doing in life all the time.

Here’s a clip of MGMT’s song, Brian Eno, from their album ‘Congratulations’, which conveniently has a cartoon surfer on the album-cover.

[This surfing metaphor reminds me of Greek philosophers’ metaphor of the kybernet or steersman, which is the origin of ‘cybernetics’. Heraclitus and the Stoics thought of the cosmos as constantly flowing and changing – ‘Everything flows’, as Heraclitus put it -, which can be distressing if you’re too attached or averse to externals. But you can learn to skillfully steer your soul and to trust in the Logos, so that you navigate the cosmic flow and have a ‘good flow of life’, in Zeno’s phrase.]

So you’ve talked about surrender as an umbrella term that encompasses four core spheres of human activity: sex, drugs or intoxicants, religion and art. All of which involve surrender.

Yes. Religion is interesting because it comes with a superstructure of belief, which I wish I could jettison.

[We didn’t have time to talk about Eno’s Catholic roots on this occasion, but, in brief, he has an interesting relationship with faith, in that he grew up in a Catholic family, went to a Catholic school and got his first experience of music from singing in the choir. But clearly he found the emphasis on sin and damnation a turn-off, and he now describes himself as an ‘evangelical atheist’.]

I belonged to a gospel choir in Brooklyn. I was the only white person in the choir and the only atheist. But the rest of the choir made me feel very welcome, and they didn’t try too hard to convert me. I think I was having the same experience as them when we were singing, but without the same structure of belief. I hope that’s what the artist does – create rich experiences of surrender, without the superstructure of beliefs.

You’ve clearly thought a lot and worked a lot around artistic inspiration, and ways of getting the ego out of the way to surrender to something deeper. Your use of the random Oblique Strategies cards is one way of getting the ego out of the way, for example, likewise cut-up lyrics or randomisation machines.

Yes. It’s like the surfing analogy again. What I think you’re trying to do is not forever be out of control, but to push into new territories by temporarily surrendering. The surfer catches a huge wave, and then takes control. You can use surrendering to be moved somewhere else. Humans have sought this experience throughout history. Every culture that we know has erected big fences around these experiences.

Yes, they become sacred, and taboo.

Some societies revere one sort of surrender and outlaw another. For example, the Victorians revered the arts, and thought of music as the closest thing to the divine, but they could never talk about sex. Other societies, like Hinduism, are better at marrying together art, sex and religion. Then in some parts of South America, religion is still married together with drugs. Every society makes its choices. But the concept of blasphemy – you don’t find that outside of religion.

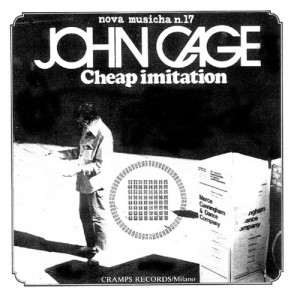

I want to explore this idea of surrendering, letting go of your ego to create. It seems to me that’s a spiritual or religious idea. So take John Cage using the I-Ching to create – the idea behind it is that when you get your conscious ego out of the way, the Tao will give rise to something meaningful and beautiful. Or Terry Riley using group improvisation – again there’s the idea something beautiful and spiritual will emerge from the spontaneity. And you’ve spoken about the idea of surrendering to the universe. You once said about gospel music:

The big message of gospel is that you don’t have to keep fighting the universe; you can stop and the universe is quite good to you. There is a loss of ego.

It seems to me that your idea of surrendering to the benign universe is not Freudian or Darwinian, where the cosmos is hostile or indifferent, and the unconscious is ‘red in tooth and claw’. It’s more Platonic or pantheist or Taoist or Judeo-Christian – it’s the idea that if you surrender to the universe, the universe will be good to you. Something meaningful and beautiful will emerge when you surrender control. That’s an expression of cosmic optimism.

I’m not a cosmic optimist. I’m an optimist, just not a cosmic optimist. f you take the ego out of the way, you start seeing the world differently, and valuing the difference. You acquire alertness, you know you’re not in control anymore and that makes you more alert.

You’re shaken out of the sleep of stultifying habit.

Yes. I don’t think you can invoke a benign cosmos. It just makes you a more effective person. It’s like if the surfer catches a big wave, they’re paying a lot of attention.

[This is interesting, although I think the state Eno is talking about is more akin to scanning your environment for threats, which seems to me a different experience to the oceanic feeling one can get in communal singing and dancing – the latter is more a wonderful feeling of love, trust and opening up, I would suggest.]

I don’t think it has to be generalized up [to God] to be anything to do with synchronicity. Synchronicity is a charming idea, and entirely unmystical.

Well…it was quite a mystical idea for Jung.

In technology and art, you see synchronicity all the time. Given certain conditions, things will inevitably happen.

The 18th century debate over whether music is mechanistic or spiritual lives on in electronic music today (photo shows a Kraftwerk concert).

That’s interesting. It reminds me of a debate in the 18th and 19th centuries about why music has the effect on us that it does. One theory was mechanistic – music works on our nervous machines, therefore one could theoretically work out the formula or programme to achieve a particular effect on our mechanisms. The other theory was more transcendent or animist – music is a daemonic bridge between humans and the divine, or what Kant called the noumenal. Which theory do you agree with?

I think there’s a third description of what’s going on, which is that it’s cultural. When you listen to a piece of music, you don’t just hear it, you hear it with reference to your whole history of listening. You hear the differences and the similarities to what you’ve heard before. If aliens listened to two string quartets, they’d probably sound exactly the same to them – like this patch of carpet and that patch of carpet. But we might hear something new and think that’s exciting.

Right – and if it’s too different, it will offend us.

It will be outside the conversation, like if speak you i to this like, you wouldn’t understand it.And likewise, if I’m saying stuff to you that you’ve heard a million times before, it will be a bit boring. Maybe I am [laughs]. We’re very attuned to differences. When I give lectures about art, I try to explain it to my students by talking about haircuts. A haircut is an art work.

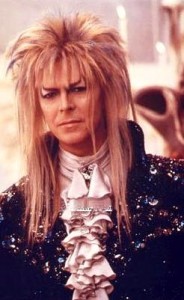

Sure – think of all the different haircuts David Bowie has had.

We make stylistic decisions, and those decisions are made in reference to our knowledge of previous haircuts, and cultural experience of what haircuts can signify. But to an alien, they probably wouldn’t see the differences between your hairstyle and…well…not mine [smoothing his pate] but someone else’s.

So the third way between the spiritual and the mechanist explanations of music’s emotional power is the cultural.

Yes. Some things may be universal, like when music gets louder it’s usually exciting. Likewise, the colour red usually evokes anger or alarm. But most things are probably culturally learned.

OK. I’d like to discuss the idea of surrender and musical performance. You must have had the experience of playing music live, in the studio or in a concert, and something magical happens. People talk about ‘magic takes’, when something stunning and somewhat mysterious happens in a take. Like, for example, when Aretha Franklin recorded ‘I Never Loved A Man’ in the Stax studio, in her very first recording session there. And something amazing happened, everyone felt it. You talk about a similar experience of recording ‘Moment of Surrender’ with U2, a song which came together in a very short period of time, and which felt (as you put it) like it was ‘channeled’ rather than made.

Yes. Sports people have a similar experience. They talk about being ‘in the zone’, moments when they can’t do anything wrong. You see it with improvisation. Musicians will do outrageous things, and you think, where have they gone, and how will they get out of that one, and somehow they do.

[The most famous example of this sort of unconscious genius in sport, by the by, is Lilliam Thuram scoring two goals in the 1998 World Cup semi-final. He doesn’t remember the game and calls it his ‘Miles Davis moment‘. The coach, Andre Jacquet, says Thuram was in ‘some mystical state’.]

But that’s nothing to do with the ‘Spirit’ descending?

I’m anti-mystical. Mysticism isn’t an explanation. It’s a way of getting rid of a problem. You don’t know what’s happening, so you call it God. I’m interested in the mechanism. What’s it mean when you talk about ‘the zone’. It’s a combination of confidence and alertness. The confidence to really go there [outside of your comfort zone], and the alertness to re-position yourself so you don’t wipe out.

I see. That’s interesting about confidence – I guess it’s also to do with confidence in technique. When Plato famously discusses the rhapsody of artistic creation, in his dialogue Ion, he says that ecstasy is inferior to technique, because poets don’t know what they’re doing when they’re in ecstatic rapture. Technique is better than rhapsody, he says, because it can be learnt and taught. But that’s always struck me as wrong – you need to master the technique before you can have the confidence to surrender, to let go, to ‘snatch a grace beyond the reach of art’ as Pope put it.

Yes. Mastering the technique can include mastering the technology. Think of Lee Perry in his studio. He gets in the zone in the most unlikely way, by doing this [mimes Lee Perry fiddling with the Studio knobs and dials]. Technique is understanding what this thing can do, and what that would mean in terms of the history of your culture.

As a producer yourself, you’ve produced some of the most uplifting and ecstatic songs of the last fifty years – David Bowie’s Heroes, Talking Heads’ Once in a Lifetime, U2’s Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For. It seems to me that, like gospel, these songs share a certain quality or belief: a belief in the possibility of a better world and a better way of relating to one another. David Byrne has written about the ecstatic experience of playing Once In A Lifetime live. He wrote in his book How Music Works:

the more integral everyone was, the more everyone gave up some individuality and surrendered to the music. It was a living, breathing model of a more ideal society, an ephemeral utopia that everyone, even the audience, felt was being manifested in front of them.

There’s a similar hope and yearning for a better world in one of your favourite songs, State of Independence by Vangelis and Donna Summer. Well, it seems to me that this idea comes from the sacred. It’s the yearning for the Kingdom, for an end to exile and suffering. That’s what Bono sings in Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For: ‘I believe in the Kingdom Come, when all the colours bleed into one’. I guess I’m saying that some of the most uplifting songs you’ve worked on do still have a sacred belief structure to them – the yearning for Another World, for the Kingdom – despite your desire to jettison this belief.

I think you’ve got it the wrong way round. You see surrender as part of the subset of religion, when I think religion is a subset of the broader experience of surrender. In the past, the only places where one was enabled to attach hope and optimism and a desire to surrender, have been religious places. That was the only area where one was allowed and encouraged to have that experience. It was what we evolved to cope with that need. But it doesn’t have to be religion that gives us that experience. It doesn’t have to be the case that religion lasts forever. Religion has in fact mutated a lot.

I’ve been reading Jared Diamond’s The World Until Yesterday: What Can We Learn From Primitive Societies, where he discusses his years among Pacific Islanders and their religious beliefs. Basically, Abrahamic religion belongs to the Middle Ages, and we’re moving beyond that now. We’re moving beyond wanting religion to do things it used to do. It used to have an explanatory role, but science has taken that place. It used to be the main source of beauty and awe, but art has taken that role. It used to be the main source of sanctions, but law has taken that role. What remains is what primitive people use it for – consolation and community-building. It is still very important in community-building. You see in South America that religion is becoming more and more local.

Then, alas, our hour is over. Attendees of Eno’s regular Tuesday evening acapella singing session are arriving, and Eno takes out the song books, filled with songs like Amazing Grace and Hallelujah. He explains: ‘Acapella singing involves surrender. Sometimes one of my famous lead-singer friends comes along, and I have to explain that they can’t be a lead-singer here. We have one coming this evening – I’ve produced four of his albums so hopefully he won’t mind me telling him what to do’. I wonder who that is…Bono? David Byrne?

Sadly, I have to depart so I don’t find out. Eno kindly offers to meet another time, once I have worked out how to use my recording machine. Next time hopefully we will get to explore his ideas on art and health (he thinks communal singing is very good for our health and well-being, and he’s also started doing art works in hospitals), and I want to challenge him about his idea that you can engineer powerful moments of surrender without also invoking beliefs. I’m not so sure that emotions can be separated from beliefs – you’re always surrendering to something or someone, aren’t you? And I’d suggest his music is still haunted by the ghost of the old religious belief-system. The spirit is there, just as it’s there in that other great synth-pioneer, Vangelis. Wittingly or unwittingly, they are Evangelions – their music seems to me to connect us to the divine. Or maybe that’s just my experience!

in my youth, i liked d bowie, but, praps due to my somewhat nihilistic upbringing, surrender to his music seemed to put me in a foreign space that i couldn’t place, so it almost made me feel a little unhinged. posting his art fairly and squarely in the ‘divine’ classification may have helped me assimilate it more ‘healthily’ for what it was, rather than trying to seek intelligible, helpful meaning in it. i guess he wasn’t a didact so much; more a sharer. his songs resonate most to me when i am a fully ‘functioning’ and relatively fulfilled member of society – a delicious spice, if you like.

Thanks for this piece!

Ace! Been fascinated with this interest of Eno’s and you’ve fleshed it out a bit more in my head. Cheers!

I agree with you entirely. Brian Eno’s music, especially with Harold Budd, opens a door to the spiritual world. It is amazing that he cannot see that! He has this gift, uses this gift, but does not know what this gift, in reality, actually is even though it is there right in front of him!

Well…obviously it’s not for me to say where his gift comes from or what it’s for – the artist does their thing, we get to enjoy it and interpret it according to our own experience.

Pingback: The varieties of spiritual experience | The History of Emotions Blog

Pingback: Love, Pain, Ecstasy, and Murder: Christmas at the History of Emotions Blog | The History of Emotions Blog