Sue Morgan is Professor of Women’s and Gender History at the University of Chichester, and an expert on the histories of religion and sexuality. In this post for the History of Emotions blog, in connection with Episode 11 of ‘Five Hundred Years of Friendshp’, Professor Morgan tells the story of the extraordinary life and three-way friendships of the feminist and preacher Maude Royden.

Sue Morgan is Professor of Women’s and Gender History at the University of Chichester, and an expert on the histories of religion and sexuality. In this post for the History of Emotions blog, in connection with Episode 11 of ‘Five Hundred Years of Friendshp’, Professor Morgan tells the story of the extraordinary life and three-way friendships of the feminist and preacher Maude Royden.

__________

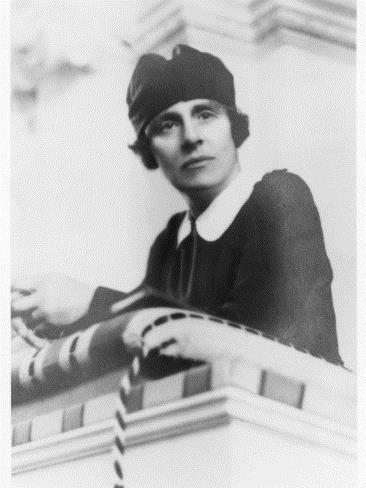

Maude Royden (1876-1956) was an Anglican feminist best known for her leadership of the campaign for women’s ordination in the early decades of the twentieth century. As an international celebrity in her own lifetime, Royden’s controversial religious leadership during the interwar years attracted dedicated admirers and enemies in equal measure. Barred from Church of England pulpits, she was appointed assistant pastor to the prestigious Congregational City Temple in Holborn in 1917 and in 1920 co-founded the Guildhouse Fellowship, a religious-cum-social meeting-place in a converted chapel in Eccleston Square, London. She attracted huge congregations for twenty years, retiring from preaching in 1936 to focus on her pacifist commitments. She featured in numerous women’s magazines, press articles and BBC radio broadcasts as the face of a modern, liberal Christianity and was described by Good Housekeeping in 1928 as ‘the best-known woman preacher in the world’. In 1930 she was made a Companion of Honour for services to the nation’s religious life.

Maude Royden (1876-1956) was an Anglican feminist best known for her leadership of the campaign for women’s ordination in the early decades of the twentieth century. As an international celebrity in her own lifetime, Royden’s controversial religious leadership during the interwar years attracted dedicated admirers and enemies in equal measure. Barred from Church of England pulpits, she was appointed assistant pastor to the prestigious Congregational City Temple in Holborn in 1917 and in 1920 co-founded the Guildhouse Fellowship, a religious-cum-social meeting-place in a converted chapel in Eccleston Square, London. She attracted huge congregations for twenty years, retiring from preaching in 1936 to focus on her pacifist commitments. She featured in numerous women’s magazines, press articles and BBC radio broadcasts as the face of a modern, liberal Christianity and was described by Good Housekeeping in 1928 as ‘the best-known woman preacher in the world’. In 1930 she was made a Companion of Honour for services to the nation’s religious life.

Royden preached and wrote prodigiously not only on religious subjects but on the leading moral and political issues of the day – from birth control to industrial relations, from modern science to the Palestinian conflict. Yet her central message throughout concerned the development and fulfilment of the individual’s spiritual and human potential; in this, the categories of love and friendship (she often used these terms interchangeably) proved fundamental. Friendship was not only a basic human need but a defining category of what it actually meant to be human. We can only discover ourselves fully through a life in community, she argued. Christianity was a social religion, thus fellowship and friendship was axiomatic to Christian practice: ‘there is a peculiar grace in the friendship we have for one another when it is associated with service to some ideal, some high interest, some great cause’.

As a woman of faith, ideal human qualities were invariably based on divine precedent. In The Friendship of God (1924) Royden described God’s love as a supreme, because unconditional (warts and all) gift of friendship, exemplary in its nature. She encouraged her readership to study Christ’s own friendships as a lesson in individual humility – we should never seek to befriend only those, she asserted, that we might consider our moral equals or superiors. True friendship should eschew social advantage or trivial sentimentality and instead be grounded in total sincerity. Christ’s friendship with his disciples, for example, was often painfully honest. Twice, she reminded her audience, Christ rebuked his beloved friend Peter, once for his misunderstanding of the Messiah’s nature – ‘Get thee behind me Satan!’ (Mark 8.33) – and once for his forthcoming treachery – ‘I tell you Peter, the cock will not crow this day, until you have denied three times that you know me’ (Luke 22.34). To love one’s friends, therefore, was to consider them capable of great things, know that they might fail, and yet to love them still.

Royden’s theology of friendship was also discussed in her bestselling work, Sex and Common-Sense where she considered the qualities of same-sex friendships both positively (their great devotion) and negatively (their alleged tendency to self-absorption). Although a strong supporter of greater social tolerance for homosexuals (she publicly defended Radclyffe Hall’s controversial lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness in 1929), she believed that love for a friend should never undermine heterosexual spousal love. Within marriage itself, of course, friendship was the cornerstone of a happy family life.

Royden experienced considerable opposition during her career as a preacher, and it was her own friendships, always intense and often unorthodox, that sustained her throughout difficult times. She was good at making friends, and successfully elicited great admiration and longstanding loyalty from co-workers such as Rev. Herbert Gray, a Scottish Presbyterian minister who co-founded the first Marriage Guidance Council in 1938 and Rev. Dick Sheppard who exercised a powerful social ministry at St Martin-in-the-Fields and whose BBC broadcast services were internationally famous. Their friendship was consolidated through joint involvement in Sheppard’s Peace Pledge Union, launched in 1935.

Three-way friendships seemed to be a distinctive feature of Royden’s life. Single until aged 68 years, she was supported emotionally by two lifelong three-way relationships. The first of these began in 1896 when Royden met Kathleen Courtney and Evelyn Gunter at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford. All three women shared common political objectives around suffrage and women’s ministry – Courtney was also heavily involved in pacifism and eventually the League of Nations. The Royden-Courtney correspondence spanned 60 years until Royden’s death in 1956. The intimacy of their friendship is emblazoned across the page. They used pet names for each other (Royden called Courtney ‘Kafleen’ and ‘mavourneen’, a Irish Gaelic term for ‘darling’), made frequent protestations of love, and exhibited suspicion and jealousy over other female friends. ‘Who is in my room? I forbid you to love her as much as me’ declared Royden, when in 1899 Courtney returned alone to Lady Margaret Hall for her final year. They also sparred intellectually on biblical criticism, theological controversies and social issues of the day, while simultaneously confessing their most intimate fears and anxieties to each other over the usefulness of their lives. In a later unpublished memoir Courtney defined their friendship as being ‘founded on…[an] affinity and community of mind..[and] intense admiration’.

Evelyn Gunter, a talented woman in her own right, chose instead to dedicate herself to Royden’s burgeoning career, acting as her events co-ordinator, housekeeper, surrogate mother to Helen, Royden’s adopted daughter and, in later life, as her carer. Gunter was also responsible for introducing her to Rev. William Hudson Shaw, an Anglican clergyman 18 years Royden’s senior who appointed her as his unofficial parish assistant after she left Oxford. In 1902, Royden went to live with Shaw and his wife Effie in the remote rural parish of South Luffenham, Rutlandshire; she would live with them, on and off, in a devoted triangle for 42 years until Effie’s death in 1944. This friendship was recounted in Royden’s memoirs, The Threefold Cord (1947), detailing her passionate yet celibate love for Shaw. Effie, who suffered with chronic mental ill health, both recognised and endorsed her husband’s intense, loving friendship with Royden. At her explicit request they married each other soon after Effie’s death in September 1944; Royden was 68 and Shaw was 85 years old. He died just eight weeks later.

A Threefold Cord is Royden’s moving testament to a friendship that we might struggle to understand fully in the twenty-first century, but which, in the absence of any apparent sexual dimension (Effie was ‘repelled by passion’ according to Royden) clearly worked for them all on many different levels. ‘Hudson and I knew that we must always think of life as including all three’, Royden observed, any sort of ‘furtive love affair’ was simply impossible. Their faith and their relentless work schedule strengthened their resolve. ‘We lived our lives to the full’, she explains, ‘we had our work—work that we loved—and were neither crippled not repressed by the discipline we accepted’. The two women also cared deeply for each other and would often gang up on ‘The Man’ or ‘the Prophet’ as they affectionately called him. Her later work commitments meant that Royden was often away travelling, but she always returned home to them in whichever parish Shaw was attached to. Thomas a Kempis’s phrase ‘without a friend thou canst not live well’ was a favourite of Royden’s – and her life bore witness to its significance.

__________

Return to: Five Hundred Years of Friendship at the History of Emotions Blog