Jane Mackelworth is a PhD candidate at the Centre for the History of the Emotions at Queen Mary University of London, working on ‘Writing Sapphic Love and Desire in Britain, 1900-1950.’ She also is a co-convenor for the IHR History of Sexuality seminar series. She is currently co-editing a special edition of the Women’s History Review on ‘Love, Desire and Melancholy; Inspired by the Writing of Constance Maynard.’ In this blog post she writes about a project which won the Richard Garriott Prize for Best Public Engagement Activity at Queen Mary in 2014. You can follow Jane on Twitter: @Jane__Victoria.

During the summer of 2014 a group of elders living in and around Bromley by Bow, in east London, shared stories about the precious objects in their lives to create a unique and moving exhibition: Love in Objects.

I didn’t know what to expect when we first started, I was a bit nervous….I needed a bit of help to start but I was so pleased with what I made. Filling our boxes with everything we loved the best…we all had different themes…I learnt so much.

Project member

The complex relation between people and objects continues to be an important theme in the history of the emotions. No longer are objects seen as passive. Instead they are seen as active agents that can produce emotions, create powerful bonds between people and shape connections between people and place.

It was with this in mind that we created the Love in Objects project; a partnership between the Centre for the History of the Emotions and local charity, the Bromley by Bow Centre, which has a thirty-year history of working in the local community. Its experience, its unique entrepreneurial approach and its belief in the capacity of everyone to achieve amazing things are what make the centre one of the leading regeneration charities in Britain today.

Over three months, thirteen elders, aged up to 85, came together at the Bromley by Bow Centre each week to share their objects and stories of love. Each member brought along one or more objects from their home which spoke to them of love and then crafted a themed box to house their object. Project members worked with professional stone carver and sculptor, Paula Haughney, who has many years experience in working in community projects, and volunteers John Lynch, who specializes in local history, and Jane Mackelworth, who specializes in the history of love and is based in the Centre for the History of the Emotions which funded the project. The project was overseen and managed by Lucy Wells, artist and Inclusive Arts Project Manager at the Bromley by Bow Centre.

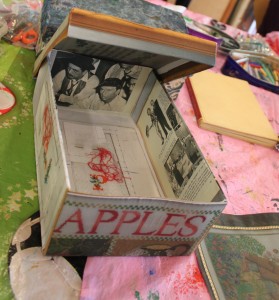

Project members decorated their boxes using marbling, an artistic technique blending coloured inks to create patterns, and then chose personal images, photographs and words to represent the object in their box, and associated memories in their lives.

Project members decorated their boxes using marbling, an artistic technique blending coloured inks to create patterns, and then chose personal images, photographs and words to represent the object in their box, and associated memories in their lives.

For example, images of Frank Sinatra were chosen by one member as a reminder of times he had spent dancing with his late wife, and an image of ‘two redcoats’ at Butlins was chosen by one member, reminding him of his time as a catering assistant at a Butlins holiday park in his youth. Another member decorated her box almost entirely in green with prints of trees, and butterflies to remind her of happy times with her children at the park at weekends many years ago; ‘Happiness. Nice weather. Sunshine…I miss my children.’ Another box is decorated with the word ‘LOVE’ and decorated in tiny Chinese lettering to represent a member’s 52-year marriage to her husband who she met in Chinatown.

Letters and notes accompanied the objects and images in each box, and members also gave personal interviews to share the meaning behind the objects they had chosen. Some key themes emerged in the objects, and representations, which people chose for their boxes.

Gifts were an important theme. Anthropologists, and increasingly historians, have recognized the way that gifts create ties between people. Gifts not only symbolize a relationship but can actually transform it. Mauss was one of the first to theorize gift giving suggesting that in giving a gift one is giving a part of the self; ‘Even when [the gift] has been abandoned by the giver, it still possess something of him’.[1] Therefore, ‘to make a gift of something is to make a present of some part of oneself.’[2] And so exchanging objects, which are a part of the self, causes selves to be joined or welded together, both with one another and with the objects concerned:

Souls are mixed with things; things with souls. Lives are mingled together and that is how, among persons and things so intermingled, each emerges from their own sphere and mixes together.[3]

This explains the value of gifts. Lewis Hyde argues for the transformational power of gifts suggesting that a gift brings with it not only the gift itself but the promise (or the fact) of transformation, friendship, and love.’ [4]

One woman selected gifts of jewellery as her objects of love explaining that they had been given to her by her three daughters over the years at birthdays and as Mother’s Day presents. Another box contained a cake decoration from a birthday cake given to the project member on her 50th birthday, twenty years ago. The decoration, made of red and white flowers and a brass embossed ‘50’ is usually displayed in her cabinet at home along with china plates. She chose it for the box because it ‘makes me feel nice’ and ‘reminds me of my birthday.’ But it also, she explained, signifies for her ‘the love of my husband and the love of my children.

Another woman also chose cake decorations as one of her objects of love. These were from her grandson’s wedding cake and she had kept them after the wedding which was ‘lovely.’ For her, the object acted as a memento of the wedding. Other members also chose specific objects which acted as a reminder of a time they had enjoyed. For example, one man chose a small ornament of Salisbury Cathedral which he had bought as a souvenir when visiting the cathedral with his brother ‘so I could remember the day.’ When he looks at the object now ‘it reminds me of going there.’

For some, the box was used to represent childhood memories, in part inspired by a talk given by John Lynch about local east London history. One woman chose a photo of hop pickers because as a schoolchild she used to go hop picking each year ‘for the whole season… September I think it was.’ She remembers the lorry collecting them to drive them down to Kent and describes lighting the fire to cook outside. Her box also contains notes of childhood memories including sleeping in the air raid shelter at night during the Second World War.

Handmade objects were also another popular choice for an objects of love. In his nineteenth century essay on gifts, Ralph Waldo Emerson, prized most highly those gifts that were handmade or hand produced:

The only gift is a portion of thyself…therefore the poet brings his poem; the shepherd, his lamb…the miner, a gem; the sailor, coral and shells; the painter his picture; the girl a handkerchief of her own sewing…But it is a cold, lifeless business when you go to the shops to buy me something.[5]

The value of handmade gifts, and handmade objects in general, was described by members who chose such objects for their boxes. One woman’s box contained pairs of little slippers that she knits herself. She knits these for her grandchildren but also for other friends and family. She spoke too of making many clothes over the years for her family, speaking of one occasion when she transformed one of her own dresses ‘outside was faded…inside perfectly nice’ into clothes for her children to wear to a party;’ I made my little son beautiful brown trousers and waistcoat.’ It is not only the finished product that it is important for her, it is the time spent doing it. It is a link back to her mother who ‘taught me when I was a child, 8 years old, cutting, sewing.’ Sewing has helped her in difficult times because it ‘makes your brain clear…I love it.’

Another member chose objects for her box which she had made during another project at the Bromley by Bow Centre. These were decorations for the jubilee celebrations, one of many that she made for others to enjoy. She describes the process using ‘thousands of pins and sequins’, explaining that ‘once you start doing it you can’t stop.’ For her, ‘A lot of love went into these things…I put love into it when I was making it.’

Once all the boxes had been made, interviews recorded, and objects and ephemera put into the boxes, they were displayed at the Bromley by Bow Centre for three months. Visitors to the exhibition reported that they found the exhibition, ‘moving’, ‘inspiring’ and ‘beautiful to look at.’ For those who took part in the project, many of whom are isolated in their day to day life, it was a chance to reflect on the importance of love in their own life:

I don’t really have anyone much to be able to talk about my husband any more. It brings back all those good times, and the sad ones mind, looking at these pictures.

Project member

I think that this group and the boxes of love we made, well it was personal and I liked that; I felt that I could connect to myself. But…at the same time it is a topic that we can all relate to isn’t it? A universal theme is good!

Project member

And the project also gave members a chance to learn new skills and to enjoy seeing their work exhibited at the Bromley by Bow Centre:

…it is great to see our work up – looks fantastic and…I’m not the only one who thinks so!

Project member

The Love in Objects project won the Queen Mary University of London Richard Garriott award for the University’s best public engagement project. The project’s success is attributable not only to the dedication and hard work of the thirteen project members but also to the partnership nature of the project. The partnership with an existing community project meant that the project was able to work with those members of the community who are often the hardest to reach in public engagement work.

The Bromley by Bow Centre’s trusted relationship with isolated community members, often with additional care needs and long term physical health problems, its longstanding partnership with professional artists with many years experience of community work, and its setting in beautiful and inspiring surroundings, helped ensure the project’s success. However, ultimately the success of the project was down to the members who shared intimate, touching and inspiring stories about the enduring role of love in their lives. Through the objects they shared these stories and memories were brought to life in beautiful, imaginative and unexpected ways.

[1] Marcel Mauss, The Gift, trans. by W.D. Halls, foreword by Mary Douglas, London: Routledge, [1925 in French] [1954 in English translation], 1990, p.15.

[2] Mauss, The Gift, 1990, p.16.

[3] Mauss, The Gift, 1990, p.26.

[4] Lewis Hyde, The Gift; Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property, London: Vintage, 1999, p.68.

[5] Ralph Waldo Emerson, ‘The Gift’, 1844.