Dr Thomas Dixon is the Director of the Centre for the History of the Emotions at Queen Mary University of London. Here, on the occasion of the publication of his new book, he reflects on his experience of researching and writing about the history of weeping in Britain…

Today is the official publication day for my book Weeping Britannia: Portrait of a Nation in Tears (Oxford University Press). It’s the culmination of a process of researching, thinking, and writing about crying that began in 2009.

Today is the official publication day for my book Weeping Britannia: Portrait of a Nation in Tears (Oxford University Press). It’s the culmination of a process of researching, thinking, and writing about crying that began in 2009.

Before I move on to a few years of anger, rage, and temper tantrums (my next research project), I thought I’d mark this occasion with a stock-taking sort of a blog post. After summarising some of the aims and ideas of the weeping book, and sharing a few of its examples, I’ve listed some of my favourite books about crying, and also gathered together a list of links to some of the other outputs that my thinking about tears has contributed to over the last few years.

So, what’s my book all about?

Weeping Britannia is an experimental book, trying to explore a nation’s history through its tears and its feelings, including its feelings about its tears, and its feelings about its feelings. I wanted the book to be both scholarly and accessible, and to connect the experiences of individuals to a larger historical narrative about emotions and ideas ranging from the late middle ages to the present. On reflection, that was a pretty ambitious set of aims, and readers will no doubt vary in the extent to which they think I’ve succeeded!

The history of emotions is where the history of ideas meets the history of the body. Weeping is an intellectual activity, and yet it is also a bodily function like vomiting, sweating, or farting. Even the lowly fart, incidentally, has been subjected to enlightening historical analysis, by Sir Keith Thomas, in an edited collection of essays on The Extraordinary and the Everyday. In my book, I locate accounts of tearful moments – moments in the lives of celebrated men and women, everyday folk, and a few fictional characters – among more reflective writings, whether in the form of literature, philosophy, science, or journalism, setting out theoretical and moral ideas about weeping in the period in question. In this way I hope to show how ideas and culture produce and shape emotions, and to bring to life a story of long-term religious, cultural, and intellectual change.

The really central idea here is that the interpretation and meaning that an individual gives to their own emotional experiences is a constitutive part of those experiences, not a secondary afterthought. So if we want to try to access the emotional experiences of the past we need to do so primarily not through 21st-century psychology, neuroscience, or affect theory, but through the available mental frameworks of earlier periods – whether those be found in medicine, moral philosophy, fiction, drama, movies, or television.

So, while I was trying to uncover some of the deeper roots of the emotions we feel today, I was also tracing the inextricably linked histories of how we represent, express, and interpret them. That included tracing the origins of the surprisingly persistent idea that there is such a thing as the British ‘stiff upper lip’ – a phantom physiological feature that continues to haunt British national identity. You can read a little more about my approach in the Introduction, which is available via the OUP website.

Of the many examples in my book, I have selected seven for this extended blog post, one from each of the centuries that Weeping Britannia covers, to give a flavour of how particular tearful individuals fit into the bigger picture, and of how an emotional archaeology such as this one has the potential to reveal the complex, often forgotten cultural and political meanings in something as simple as a tear…

The author of the earliest surviving autobiography in English, Margery Kempe was a businesswoman, wife, and mother living in King’s Lynn in the fifteenth century whose dramatic religious visions – including hearing beautiful heavenly music and conversing with Jesus and the Virgin Mary – inspired her to a life of devotion and pilgrimage. The hallmark of Margery’s boisterous style of devotion was loud and prolonged weeping – sometimes over the fallen world, sometimes over her own sins, sometimes over the passion of Christ, and sometimes triggered indirectly by the sight of a suffering animal or young man who reminded her of Jesus. Her weeping irritated many, even among the clergy. The Archbishop of York asked Margery, ‘Why do you weep so, woman?’, to which Margery replied firmly, ‘Sir, you shall wish some day that you had wept as sorely as I.’ Margery is described in a comprehensive recent study of tears as the all-time ‘weeping champion’ of recorded history. Her crying was certainly extreme, but it also reflected practices that were common features of medieval piety, including tearful affective meditation over the sufferings of Christ, and the shedding of tears for souls in purgatory.

Niccolo dell’Arca’s late fifteenth-century representation of the mourning Marys, in the church of Santa Maria in Bologna. (Jenny Audring/Flickr)

- Thomas Cranmer

One of the deeper roots of the twentieth-century ideology of the ‘stiff upper lip’ was the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century. Weeping had been central to several aspects of Catholic religion, including penitence, confession, the cult of the Virgin, and the mourning of the dead. In the Catholic worldview, tears could do things, including having real consequences for the souls of the wept-for departed. For Protestant reformers, both the domain and the power of tears were reduced. Weeping became primarily a solitary act of grief over sin rather than a collective act of mourning, and it had no power over the fate of the dead, or the will of God. Tears featured very rarely in Thomas Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer. By contrast, the Sarum Missal (the most widely used Catholic rite in England prior to the Reformation) had included an entire votive mass designed to draw forth ‘abundant rivers of tears’, and references to the tears of sinners assuaging the anger of God. The Protestant attitude was embodied in Thomas Cranmer’s behaviour as well as his liturgical reforms. It was said of Cranmer that he never allowed his demeanour to reveal his feelings in public but ‘privately, with his secret and special friends, he would shed forth many bitter tears, lamenting with the miseries and calamities of the world’. Archbishop Cranmer, it would seem, was a defender of the view that if you really have to cry, you should do it in private. Not all Protestants were so restrained as the Anglican Cranmer, however, and though they continued to disdain Catholic ‘wailing’ over the dead, they developed their own distinctive, charismatic forms of tearful religion, weeping in response to open air sermons, in despair at their sinfulness, or in the exquisite joy of Christ’s love.

- Ann Bodenham

In researching the history of tears I also wanted to investigate those who did not, could not, or would not weep, and what was thought of them. According to early modern sources, for instance, those who were unable or unwilling to weep included Stoics, Vikings, the Swiss, tigers, bears, wolves, werewolves, and witches. At the trial of the elderly cunning woman Ann Bodenham in Salisbury in 1653, two women were examined: a maid who claimed she had been bewitched by Bodenham, and who shed tears as the verdict was read out, and Bodenham herself who was found guilty of all sorts of extraordinary acts of devilry, including turning herself at different times into a dog, a lion, a bear, and a wolf. The account of the case described Bodenham as ‘a woman much addicted to Popery, and to Papistical fancies’. Yet she lacked the Catholic’s ability to shed tears. Bodenham would ‘make a noyse as if she wept’ but under close observation ‘she was never seen to let fall a tear’. However, even if Ann Bodenham had managed to produce a few tears at her trial, they would most likely have been met with the claim that these were not true tears revealing a contrite inner nature, but rather a mere pretence turned on and off at will. This is the witch’s dilemma, an insoluble conundrum for women who have been subjected to it in various forms ever since: tears are signs of female cunning, dry eyes of devilish inhumanity.

- Robert Burns

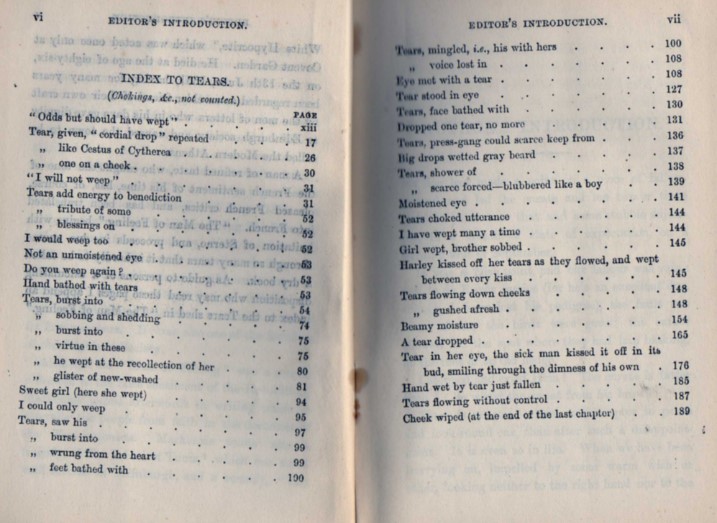

The eighteenth century saw the rise (and fall) of the ‘cult of sensibility’ – a broad movement which encompassed everything from sentimental novels and weeping plays to paintings of dead birds and sermons about fallen women. The Edinburgh lawyer and writer Henry Mackenzie’s novel The Man of Feeling, featuring a sensitive hero named Harley who weeps in sympathy with beggars, prostitutes, orphans, and lunatics, was published in 1771, at the peak of the wave of literary sensibility. It remains the most famously tear-soaked text not only of the sentimental genre, but in all of English literature. One of the book’s most ardent admirers was the young poet Robert Burns, who carried his copy around with him constantly, until it fell to pieces. Burns described The Man of Feeling as ‘a book I prize next to the Bible’. Later critics of all the lachrymose poetry, prose, pictures, and performances of this period claimed they were tainted by a shared ancestry with the ideals of the French Revolution – a dangerous philosophy teaching that sympathetic feeling was a natural, in-born virtue found in all men and women regardless of rank, and felt towards all living things, human and animal. A Victorian edition of Mackenzie’s Man of Feeling included a satirical ‘Index to Tears (Chokings, etc., not counted)’, which ran to forty-seven cases, inviting readers to laugh rather than cry over the book.

The introduction to this 1886 edition described the novel as a rehearsal of the ‘false sentiment’, borrowed from Jean-Jacques Rousseau, which had led directly to the French Revolution.

- Queen Victoria

The Victorian age has a dual inheritance in our collective imagination – an emblem of both sentimentality and repression. These two Victorian legacies correspond to two different images of the woman for whom the age is named. First there is the eighteen-year-old whose accession was proclaimed at one of the windows of St James’s palace in 1837. As soon as Victoria appeared, the crowd responded with cheers and applause, at which, it was reported, the new monarch ‘burst into tears, which continued, notwithstanding an evident attempt on the part of her Majesty to restrain her feelings, to flow in torrents down her now pallid cheeks, until her Majesty retired from the window.’ The early Victorian age was baptised in tears. Its most successful writer was the sentimental creator of Little Nell and Paul Dombey, Charles Dickens, and the young queen’s journal entries record tears forever welling up and overflowing from the eyes of her first Prime Minister, the beloved Lord Melbourne. By the end of her reign, however, Victoria had become a forbidding widow and Empress of India, a title conferred on her in 1876. The 1870s marked a turning point not only in Britain’s history but also in its dominant emotional style, as pathos gave way to restraint. It was into a world of militarism and imperialism that the ‘stiff upper lip’ would be born, a characteristic affectionately mocked by a Gershwin song of that title in the 1937 movie A Damsel in Distress.

- Anna Neagle

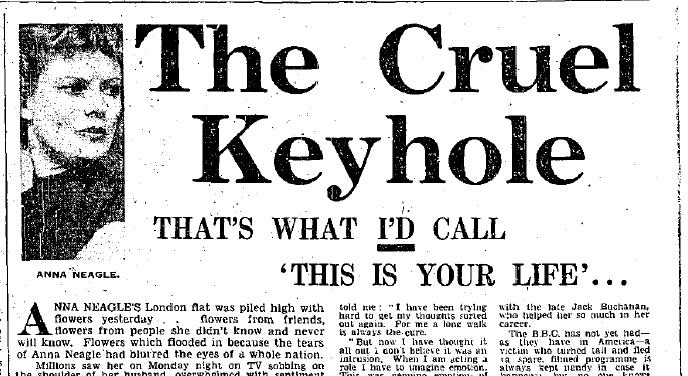

When I started the research for Weeping Britannia, I already knew that I would need to say something about the rise of reality television as a conduit for emotional tears in the twenty-first century. During the twentieth century, television programmes, along with movies, pop music, and sporting events, replaced other public spectacles, including hangings, sermons, trials, political gatherings, and state ceremonies, as the most important occasions for the shared experiencing of communal emotion. What I was surprised to discover, however, was how far back the trend for lachrymose ‘reality’ television can be traced. Even by the 1950s, American culture had a reputation for greater emotionality, and its influence was discernible in the slow and gradual work of dismantling the British ‘stiff upper lip’. In 1953, the Daily Express reported that the most popular show on American TV was a new ‘weepie’ called This is Your Life. The format was imported and broadcast by the BBC from 1955 onwards and it immediately gained a reputation as a tear-jerker. In 1958 the film star Anna Neagle was the ‘victim’. ‘Anna Neagle Weeps Before TV Millions’ was the Daily Express headline (the main cause of her tears had been a clip showing her friend and colleague Jack Buchanan, who had recently died, singing to her in one of their early films). Press coverage denounced the programme for its unforgivable intrusion into the star’s private emotions.

Neagle herself, however, was quoted as saying that she had reacted with a ‘genuine emotion’, adding ‘I know the public is not adversely affected by genuine emotion – it’s only false emotion which makes them shy away.’ The descendants of such programmes still fill our prime-time schedules, and provide plenty of opportunity for emotion, whether artificial or genuine.

- George Osborne

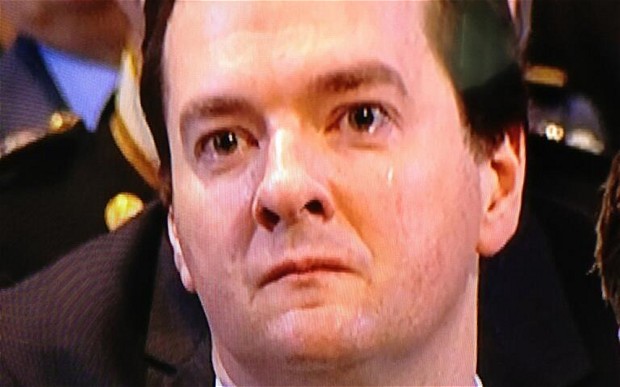

During the several years I was working on this book, it was hard to keep up with all the regular and various news stories about weeping athletes, weeping politicians, and weeping celebrities. One of the contemporary events that particularly resonated with my historical research was the much-discussed tear that made its way down the cheek of the Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, as he listened to the eulogy to Margaret Thatcher at her funeral in 2013.

At the time I was immersed in research into pre-Reformation mourning rituals, which included the tearing of clothes and hair, keening lamentations, and the kissing of the corpse. In comparison, Mr Osborne’s tear, shed for the former leader of his party, seemed a mild response. It is suggestive of a persistent strand of Protestant austerity in the matter of mourning that George Osborne’s funeral tear caused a national inquisition. Osborne was grilled on BBC Radio 4’s The Today Programme by John Humphrys who wanted to know whether Osborne was generally the ‘sort of person’ who wept, rather than being too ‘macho’ to show his feelings. The Chancellor replied, guiltily and defensively that he was caught on camera so there was no point denying it, but that the occasion was a ‘powerful’, ‘emotional’ and ‘moving’ one and that the combined effects of the sermon, the music, and the ritual of a state occasion did make him ‘well up a bit’, although he thought ‘weeping’ was a bit strong. The wider response to Thatcher’s death also revealed the long afterlife of centuries-old beliefs about tears and their absence in hard-hearted women, when opponents of Thatcher started a campaign to get the song ‘Ding Dong the Witch is Dead’, originally from the film The Wizard of Oz, to the number one spot in the music download charts, even though, in fact, Thatcher had been one of the twentieth century’s most lachrymose politicians. The witch’s dilemma is still alive and well.

My favourite books about crying:

I’ve included Amazon links for these books, although some of them are less affordable than others. These are just a few favourites and good starting points:

- James Elkins, Pictures and Tears: A History of People Who Have Cried in Front of Paintings (New York: Routledge, 2001).

- Marjory E. Lange, Telling Tears in the English Renaissance (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1996).

- Tom Lutz, Crying: The Natural and Cultural History of Tears (New York: Norton, 1999).

- Judith Kay Nelson, Seeing Through Tears: Crying and Attachment (New York: Routledge, 2005).

- Jerome Neu, A Tear is an Intellectual Thing: The Meanings of Emotion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

- Anne Vincent-Buffault, The History of Tears: Sensibility and Sentimentality in France (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1991).

- Ad Vingerhoets, Why Only Humans Weep: Unravelling the Mysteries of Tears (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Return to the top of this post.

Links to some other tearful outputs from the last few years…

- ‘History in British Tears: Some Reflections on the Anatomy of Modern Emotions’ – keynote at the annual conference of the Netherlands Historical Association (2011).

- My interview for Jo Brand’s TV documentary ‘For Crying Out Loud’ (2011).

- Appearance with Jo Brand on BBC Radio 4’s ‘Woman’s Hour’ discussing her documentary – starting about 28 minutes in (2011).

- ‘The Tears of Mr Justice Willes’ – an open-access research article in the Journal of Victorian Culture, where I first tried to write about the topic at some length (2012).

- ‘Enthusiasm Delineated: Weeping as a Religious Activity in Eighteenth-Century Britain’ – another open-access article, published in Litteraria Pragensia: Studies in Literature and Culture (2012), which was also the basis for my chapter entitled ‘Weeping in space’ in the 2015 volume, Spaces for Feeling, edited by Susan Broomhall.

- ‘Never Repress Your Tears’ – a short article for Wellcome History, exploring 19th-century medical opinions about weeping in France and Britain (2012).

- Three blog posts I wrote to accompany the BBC Two series ‘Ian Hislop’s Stiff Upper Lip: An Emotional History of Britain’ (2012), for which I was the academic consultant.

- ‘The Waterworks’ – a reflective essay on the meaning of tears for Aeon magazine (2013).

- BBC Radio 3 Sunday Feature (45 mins) produced by Natalie Steed: ‘Margaret Are You Grieving: A Cultural History of Weeping’ (2013).

- ‘Tracks of my tears: The mystery of crying’ (2013) – contributor to episode of ‘The Body Sphere’ on ABC Australian radio (audio and transcript).

- ‘When the crying stops’ – article about Titus Andronicus and the science of weeping in the Shakespearean age in Viewpoint – the magazine of the British Society for the History of Science (2013) – also re-posted on the History of Emotions Blog.

- A series of podcasts made with Clare Whistler, Natalie Steed, and others, exploring historical and contemporary meanings of water and tears, including a new setting of a George Herbert poem by Kerry Andrew (2013-14).

- Other posts relating to Clare Whistler’s work as Leverhulme Artist in Residence at the QMUL Centre for the History of the Emotions, 2013-14.

- My review of the Disney Pixar movie ‘Inside Out’ for The Conversation (2015).

- ‘Aylan Kurdi: A Dickensian moment’ – a short essay for the OUP blog reflecting on tears, emotions, and the debate about refugees (2015)

Return to the top of this post.

Follow Thomas on Twitter: @ThomasDixon2015