Sara Hiorns is a doctoral researcher at Queen Mary University of London. She was awarded an AHRC studentship in 2013 for the project, ‘The diplomatic service family at home and abroad since 1945’ which is joint supervised by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and Queen Mary. She has worked for HM Diplomatic Service since 2004, and is working on a novel that attempts to deal with the aftermath of the Kindertransports, via children’s memories of migration. You can follow Sara on Twitter: @TheHiorns. In this post Sara reflects on her own British heritage and the experience of unexpectedly crying in the archive while undertaking historical research.She is currently writing a book on Diana Bromley.

This blog post is about the day I cried in an archive.

As I get older, I’ve found myself being moved to tears more often, but like some of Mass Observation’s lachrymose cinema-goers of 1950 who appear in Thomas Dixon’s Weeping Britannia, I too feel self-conscious, embarrassed and foolish when this happens. If you were to ask me why I feel this way, I would make the telling joke, “It’s because I’m British.” People often remark on my pronounced Britishness. They say it comes out in my well-made cups of tea and my sense of humour.

When I left the British Library (where the unfortunate incident took place) that day I bumped into Rhodri Hayward from the Centre for the History of the Emotions. I felt washed out and that my mascara had suffered (and also hugely moved but never mind about that) so I invoked my humour immediately “You’ll be interested in this,” I said, “I just wept freely in an archive.” “Write us a blog post,” Rhodri said.

C. R. W. Nevinson’s 1940 painting captured the Blitz spirit. It was entitled, ‘Cockney Stoic; or Camden Town Kids Don’t Cry’.

Although I’d said I’d think about it, I had no intention of writing a blog post. Dixon comments in Weeping Britannia that throughout his lifetime “stiff upper lips have been slackening” (p. 4) and though I wouldn’t imagine there’s a huge difference in our ages I’d say that process has largely passed me by. My older parents had both lived through the war (my Dad in the Western Desert, my Mum in the London blitz) and had not so much conveyed as hammered home to me that crying was, in their favourite expression, “weak-kneed”.

Later, at home, the content of the material that had made me cry kept coming to mind, along with my unusual reaction to it and I began to see that there were similarities between the people I’d been reading about and myself. We shared national characteristics (and the spectre of a world war), we shared a career and we shared a reluctance or inability to express ourselves adequately. Curious, I thought I would write a blog post after all, and this is it.

Sitting in the British Library Newsroom in front of a microfilm copy of The Daily Express for 5 December 1958 I wrote in my notebook:

Diana – at home

Tom – at Cabinet Office

Boys – at school. 13 days left alive

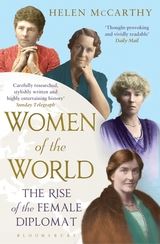

Since 2013, when I took a sabbatical from my Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) job to begin a PhD on the children of British diplomats in the postwar period, I’d been aware of the story of Diana Bromley. My supervisor, QMUL’s Helen McCarthy, gave me a sneak preview of the final  chapter of her book Women of the World: The Rise of the Female Diplomat which begins with a description of the Bromley case. Bromley, a wife and daughter of British diplomats was, according to the Senior Medical Officer at Holloway Prison, suffering from ‘melancholia’ when she killed her two sons, Martin aged 13 and Stephen, 10, and tried to kill herself on 18 December 1958. The murders gave rise to a greater interest in (hitherto neglected) pastoral care for Foreign Office families and led to the formation of the Foreign Service Wives’ Association in 1960.

chapter of her book Women of the World: The Rise of the Female Diplomat which begins with a description of the Bromley case. Bromley, a wife and daughter of British diplomats was, according to the Senior Medical Officer at Holloway Prison, suffering from ‘melancholia’ when she killed her two sons, Martin aged 13 and Stephen, 10, and tried to kill herself on 18 December 1958. The murders gave rise to a greater interest in (hitherto neglected) pastoral care for Foreign Office families and led to the formation of the Foreign Service Wives’ Association in 1960.

I found it difficult to find direct relevance in the Bromley case. I felt it was a tragic catalyst for positive change, but in no way a typical example of diplomatic family life. It was difficult even to advance the theory that the Foreign Office was in some way to blame for what happened. A 10-minute court hearing on 18 February 1959 found that Diana Bromley was unfit to plead due to insanity and that she had been treated in mental hospitals three times in the past: her mental illness was an established fact.

Then, in August this year James Southern, my FCO/QMUL colleague who’s working on social diversity in the Foreign Office, sent me part of an interview he’d conducted with two elderly retired diplomats. Talking about the phenomenon of the Foreign Office wife, they stressed the need for resilience in unfamiliar and demanding climates, and within the negligent and equally demanding hierarchy. Their generation of wives had managed well, they felt, because they had lived through the war. But they mentioned one exception, a woman they described as “Eurasian”, and not “pure” British, who “hadn’t known how to integrate”. She, they said, had become very isolated and depressed and had killed her children and herself.

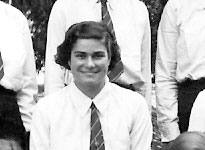

An image of Joan Hunter Dunn (later known as Sir John Betjeman’s muse) as headgirl of her school in the 1930s. (c) John Morrison, via The Today Programme website.

I was fascinated by what I read. The FCO seemed to have given rise to not one, but two child murderers: it seemed impossible. But I also knew that Diana Bromley was the daughter of an extremely distinguished British diplomat and well known specialist in the Far East, Sir John Pratt. There was no way, I felt sure, that Bromley could be described as “Eurasian” – that outmoded catch-all for people who weren’t quite-quite – what we’d now describe as “mixed race”. It was extremely unlikely that someone who had had a Foreign Office career in the early years of the twentieth century (Diana was born in 1918 while the Pratts were in China) would have made an inter-racial marriage. In my mind’s eye, I persisted with a very English image of Bromley: a Joan Hunter Dunn, raw-boned and gawky. I couldn’t believe that she might lack resilience. Maybe, I speculated, her status as an old hand made her scornful of the new wives, maybe they had been in awe of her pedigree – maybe it was a class thing?

It was also an interesting situation from a research point of view, illustrating as it did the limitations of the oral history interview, a method that has formed a large part of my research. Surely it threw into question the integrity of the recollections of those who’d lived long and full lives? I went around making discreet inquiries about a second set of child murders related to the Foreign Office but got nowhere. In the end, I asked James if he could go back and ask the woman’s name and they told him it was Diana Bromley.

As soon as I heard this, I became desperate to see a picture of her, the Eurasian thing was a red herring I’d decided. James’ correspondents were mixing her up with someone else. This is why I elected to look at The Daily Express in the British Library. I’d glanced at The Times coverage in the past and found it an informative but dry account of the murders. I hoped The Express would be more detailed and that it would include photos.

But I know now, after a great deal of reflection, that I chose The Express for a reason. In her brilliant article “Touching the void: Affective history and the impossible”(2010) Emily Robinson attempts to unravel the “intensity of the archival encounter” by examining the historian’s emotional responses to archive material (and the archive itself) and suggesting possible explanations for them. It’s Robinson’s contention that “Emotions govern both our choices of topic and the ways in which we approach research.” Even those historians – like many of those I’ve encountered in Whitehall, who set great store by their objectivity – approach their goal in an emotional way, investing objectivity with emotion, making it “a kind of historian’s super-ego” as Robinson nicely puts it.

I didn’t, I realise now, choose the Daily Express for reasons of objectivity. Quite the reverse. When I was growing up it was my Dad’s paper of choice and he had read it throughout his life. In 1958 he would have read it sitting in the home he shared with his first wife, smoking his way through the 60 cigarettes he dispatched every day. He was forty three that year. As I wound through December 1958 I was aiming for a sense of what it had been like to live in England at the time but soon realised that I already had a good idea. My Mum, who had turned twenty three in August, had been enjoying life, and, a great teller of stories, had peopled my childhood with the characters who appeared regularly in the pages in front of me.

Thus I knew that in 1958 Duncan Campbell was the fastest man on earth and that there was still huge affection for Winston Churchill. As blondes went, Diana Dors was the home grown favourite while Jayne Mansfield received more coverage than fellow American Marilyn Monroe. My Mum had been a great fan of comedy. As I was growing up, we listened to and endlessly quoted The Goon Show and Hancock’s Half Hour – all of whose players were riding high. Peter Sellers was appearing in Brouhaha at the Victoria Palace, Hancock had gone on holiday “to the continent” with his wife. Suez still occupied the international news and the shaken public consciousness. Schweppes mixers were popular (“Have a schwepping good Christmas!”) and Babycham seemingly essential. The price of turkeys was down, setting Britain on course for its best Christmas dinner since the war. At the top of the hit-parade was Lord Rockingham XI with “Hoots Mon” (There’s a Moose Loose Aboot this Hoose) and I suddenly remembered my Mum once saying “That bloody song was everywhere one Christmas.”

As I read I thought about Diana’s sons, Martin and Stephen, at prep school in Kent, getting ready for the Christmas holidays. I wondered if they’d liked the silly pop song, the sort of thing that boys like. They must have been preparing end of term shows, singing carols, getting excited. According to reports they’d last seen their mother in November when she visited them for half term. If her depressive illness was obvious to them in the way it had been to others, did they get a chance to articulate this in the inexpressive prep school environment? Did they, like many of my interviewees when they remember their boarding school days, worry and feel responsible for her? By this time, Diana’s father Sir John was 82, and was becoming anxious and forgetful. She was his only child and they had spent a lot of time alone together after her mother’s death in 1937. The letters he wrote to her in the late fifties show his mounting concern. He urged her to come and stay with him: the spare room was comfy, he said. He tried to tempt her to London from her Surrey home with theatre tickets and lectures. He complained that when he telephoned she didn’t answer.

Tom Bromley, Diana’s husband, was the subject of the Daily Express headline on 20 December 1958 “SECRETS MAN FINDS HIS SCHOOLBOY SONS LYING DEAD.” (At this point Diana herself hadn’t been implicated.) Also included on the front page was the Bromleys’ wedding photo and I saw it with what Emily Robinson, describes as the “intense jolt of recognition” that accompanies “the shock of archival discovery” (p. 514). Diana Bromley was not the English type I had imagined. She was very beautiful and there was no doubt that she was mixed race. She stands in direct contrast to her husband’s pasty, cheerful Englishness. Even the article comments slyly on her “Eastern type of dark beauty.”

That sudden sight of Diana Bromley on the front page of a national paper made me cry. Robinson writes that “uncovering a key piece of evidence… confirming or unsettling a narrative will be familiar to any historian” (p. 507). If it makes sense at all, I felt that the confirmation of something unexpected had unsettled me. And yet, as crazy as it may sound, I felt that I’d always known how she’d look, almost that I’d seen her somewhere before. I was fascinated, then, when Rhodri sent me “Touching the Void” to read that Robinson posits psychoanalytic theory and, in particular, Freud’s theory of the unheimlich, the uncanny, as one possible explanation for the intensity of the historian’s reaction to archival material. She writes: “For Freud the unsettling nature of phantoms and coincidental repetitions is not their strangeness but their repressed familiarity” (p. 514).

As soon as I saw Diana Bromley’s photo and related it back to the remarks about her not being “pure British” I felt I knew that the way she looked, her “Eastern type of dark beauty” had in some way contributed to what had happened. She had become isolated. Why? Possibly because people talked behind her back about her being a “halfcaste”. I pictured my Dad, who took and failed the Civil Service exam in his teens, expressing horror that the kind of men he admired, ensconced in Whitehall – that supposed great powerhouse of the intellect – got married to women who could commit such visceral acts. I imagined the newspaper readers taking in details about the Bromleys’ home and lifestyle and reacting with wicked envy, having their suspicions about the callous way the upper class treated their children confirmed.

The sight of Diana Bromley provoked from me a gradual, then unstoppable flow of tears. Because I’m not a practised weeper I don’t have a ready formed strategy. I thought briefly about leaving to cry more privately in the Ladies, something suggested by Algo60, an online presence quoted in Weeping Britannia, who wrote “If you need to blub, go into the bog and do it privately” (p. 4). Algol60’s language is interesting, dated yet schoolboyish, suggesting a frustrated prep-school type. Rejecting the sudden exit, hand over face (something that often happened at my girls’ school) as further “making a show of myself” I hunched up and let the tears fall into my lap, wiping my face with my knuckles. Of course I didn’t have any tissues because I don’t often cry and I didn’t have a cold that day. I even formulated a story in case anyone was un-English enough to come to my aid (no one was, thank God). “Oh no,” I would have said, “I’m not crying – it’s a problem with my eyes which is exacerbated when I look at a microfiche machine.”

When I’ve spoken to people about Diana Bromley, some have suggested I have more sympathy for her than for the sons that she killed, or the others who were left behind. While I don’t for a moment condone what she did, I don’t blame anyone else in the case either. I think that the culture that held them is largely to blame. In particular the entrenched emotional stoicism of British culture of the late 1950s, 8 years after that sample of British society, some of whom had identified a difficulty, an unwillingness to express their feelings in response to the Mass Observation questionnaire about crying at the movies.

Diana Bromley’s two sons were probably so well steeped in the prep-school traditions of obedience to hierarchy that they were too well-trained to refuse to take the barbiturates she gave them on the day they died. Her elderly father was concerned for her but unable to say so, referring in letters to her three psychiatric hospital admissions as “The upset you had a little while ago.” The culture of the diplomat is in some way linked too; we are always looking for a “form of words”, a set precedent, rather than speaking our minds. Very little exists to indicate the feelings of Tom Bromley following the loss of his family. Newspaper reports of the 10-minute hearing state that he often turned around to look at his wife, and one paper says – heartbreakingly – that he smiled at her. His Times obituary read: “Tom Bromley was a cultured, sensitive and intensely private man. … Inevitably, with his wife committed to custody, he withdrew from society but was able to go on to occupy more ambassadorial posts than are given to most diplomats.” At first I resented him for his continued career, his seeming lack of emotion. But what else was available for him to do in the circumstances? If he had chosen to give up work, to sit at home alone, he might have been driven to drastic action too.

Diana Bromley and her family were products of the culture of putting up and shutting up and hoping for the best. Of not having the space to articulate cultural or mental differences and of – probably – not crying. They were people who were unused to speaking plainly and unwilling to do so. They were unfamiliar with expressing emotions: and they were finally blown apart by a hateful excess of belated expression that left them all bereft.

NOTE: Since writing this further research has revealed that Sir John Pratt’s mother – Diana’s grandmother – was Anglo-Indian. Diana’s Great Aunt – her grandmother’s sister – was Anna Leonowens who wrote the book “The English Governess at the Court of Siam”, which inspired the musical, The King and I. Leonowens went to inordinate lengths to conceal her mixed race background. It’s possible that Diana’s looks “skipped a generation”.