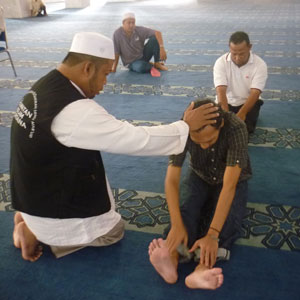

A Ruqyah healer in Indonesia

In 2010, a tense, clandestine meeting took place in a coffeeshop behind a mosque in Whitechapel. On one side of the table sat a handful of practitioners of Islamic spiritual healing (which is known as ruqyah). On the other side sat psychiatrists from the East London NHS Foundation Trust. There was a certain amount of suspicion on both sides – psychiatry has a long history of pathologizing religious belief, while British Muslims are less likely than non-Muslims to seek mental health support from the NHS, and more likely to report dissatisfaction with mental health services (see page 12 of this report). So ruqyah healers and NHS psychiatrists have been in competition for the care of souls. But could they work together?

Bringing the two sides together were two men – Dr Nigel Copsey, a former priest and Team Leader for Spiritual and Cultural Care within the East London and City Mental Health Trust, and Imam Qamruzzman, a Bangladeshi Muslim Imam. Copsey has spent the last 20 years improving spiritual care in East London mental health services, engaging with the rich variety of spiritual groups within East London, including Pentecostal, Catholic, Muslim, and African healers.

At a recent presentation at Queen Mary, University of London’s psychiatry department, Dr Copsey said: ‘The spiritual has always been marginalized by psychiatry. Psychiatrists operate from a frame which excludes the spiritual most of the time, while our community includes it. The default for Bangladeshis is to go to a traditional healer first, and faith groups also often have a frame that exclude NHS mental health services. I would love a true dialogue between mental health services and religious and spiritual groups, to help the person as best we can.’

Of course, a dialogue involves challenges. NHS mental health services operate from a secular framework, which ruqyah healers may attribute emotional disturbances to possession by a djinn, or demon. Both frameworks can be harmful for a person – psychiatry can insist on a narrow biomedical explanation for a person’s suffering which denies their experience has any non-physical meaning; while religious healers can insist on demonic possession as the cause of everything from depression to homosexual desires. The unskilled application of either of these frameworks can exacerbate a person’s suffering.

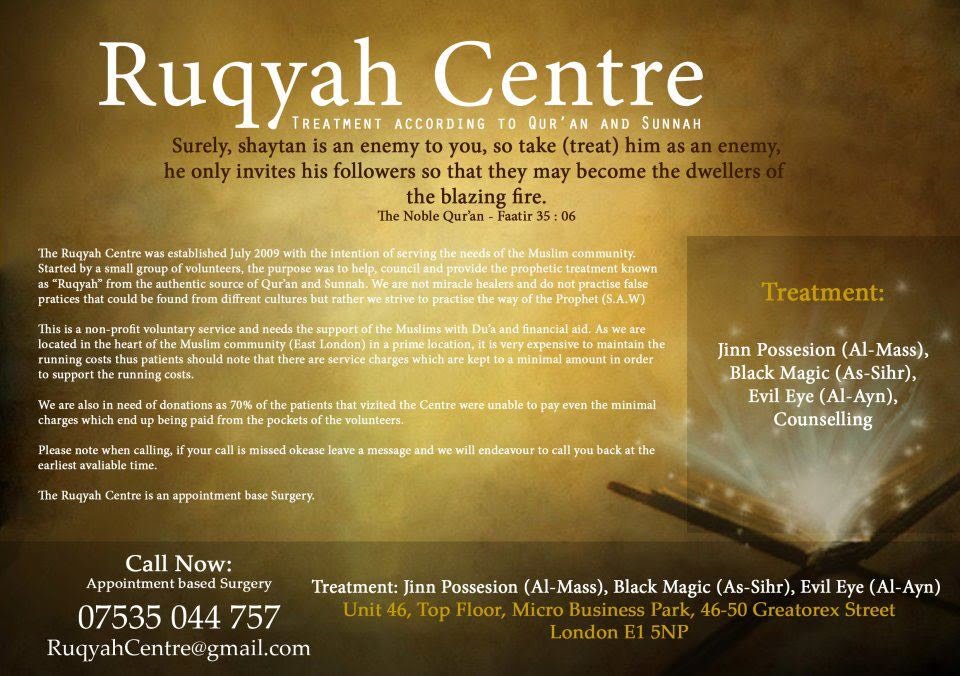

An advert for Ruqyah healing in London

Dr Angela Byrne of the East London NHS Foundation Trust says: ‘Therapists often feel anxious and unskilled when patients talk about their spirituality. We get asked a lot about ruqyah and had a prejudice towards it – we saw them as charlatans. It’s been an incredible journey working with them, and quite mind-blowing for someone like me with a secular framework.’ She was struck by some similarities between ruqyah counselling and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy – an emphasis on a person’s values, beliefs, attitudes, meaning, on hope, equanimity, endurance.

Imam Qamruzzman says: ‘We had to distinguish between genuine ruqyah healers, who are gifted and experienced at counselling, and charlatans charging high prices for amulets. Genuine healers offer counselling which helps people to receive illnesses with patience, prayers and community support – the Prophet went through suffering too.’

Professor Simon Dein, honorary professor at QMUL’s psychiatry department, is one of the UK’s leading researchers into religious healing. He also spoke at the presentation. He said: ‘Thirty years ago, religion was a taboo subject in medical schools. It was called a ‘non-tenure factor’ – you were at risk of losing your job if you researched it. It only became fairly respectable in the last 20 years. Now there’s much better understanding that religious faith is not bad for your mental health, on the contrary. For example, there’s a significant inverse relationship between heart disease and levels of religiosity. There’s a lot of research into the health benefits of meditation, including better cardiovascular functioning.’

What about the healing effects of prayer? Professor Dein says that meta-analyses have found little differences in physical outcomes for people being prayed for versus people who are not. However, in his own research into spiritual healing in Pentecostal communities, he’s concluded that ‘spiritual healing can have a great effect in psychological well-being’. He adds: ‘there’s an emphasis on the healing of memories, which is analogous to psychotherapy’. Many types of religious healing incorporate trance or hypnotic states, which can unlock the placebo response. Dein says: ‘Trance is essential to spiritual healing, but it hasn’t been much studied by psychiatry, it’s more a focus of anthropology.’

Can religious groups work together with mental health services? This project, and others like it, suggest it is possible. After all, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy came from the spiritual tradition of Stoicism, which deeply influenced both Christianity, Judaism and Islam, while Mindfulness-CBT is influenced by Buddhism and Hinduism. Professor Dein noted that some forms of CBT have emerged which tailor their approach to particular religious sensibilities, such as Christian psychotherapy and Muslim CBT, and there is some evidence that these have slightly better outcomes for their target groups than secular CBT. More importantly, a better dialogue can help encourage British Muslims to access psycotherapy without seeing it as a threat to their religious faith.

Here is a report by the Tavistock Institute on working with traditional African healers in East London.

This post is part of a series we’ll be posting this week for Mental Health Awareness Week. In 2015 the Centre for the History of the Emotions was awarded a grant of £1.6m by the Wellcome Trust for a five-year inter-disciplinary research project entitled ‘Living With Feeling: Emotional Health in History, Philosophy, and Experience’. The project, one of the first to receive a Wellcome Trust Humanities and Social Science Collaborative Award, will connect the history and philosophy of medicine and emotions with contemporary science, medical practice, phenomenology, and public policy, exploring the many varied and overlapping meanings of emotional health, past and present. You can find out more on the project website.