This is the second of two posts about the Music and Emotions Concert held at Barts Pathology Museum and supported by the QMUL Centre for Public Engagement. You can read the first post on this blog.

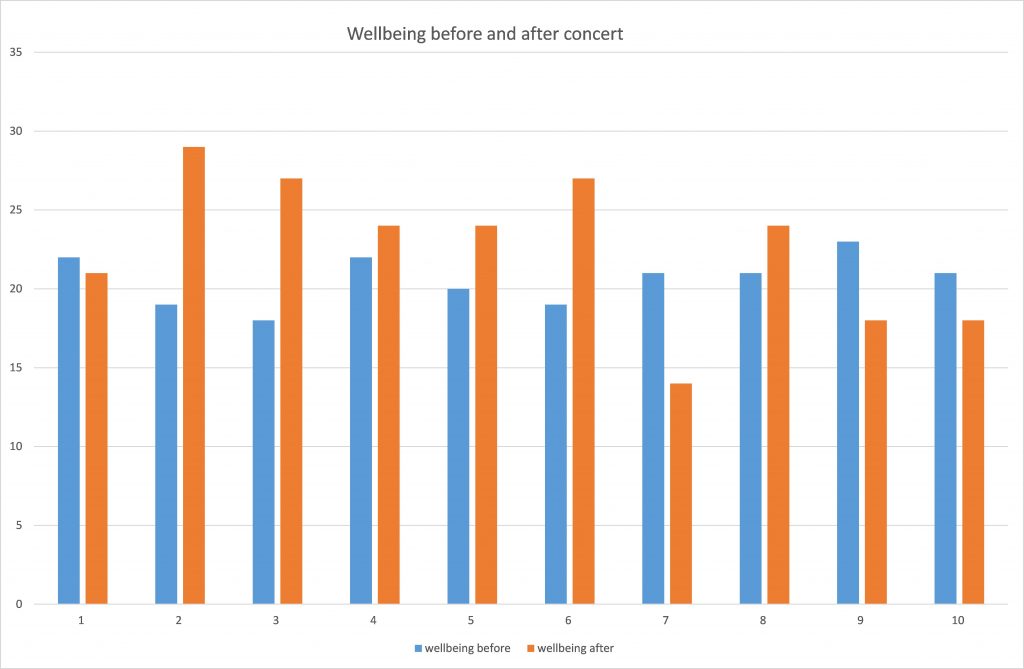

So what did the results of our wellbeing umbrellas and questionnaires show? Unfortunately we had some problems with the wellbeing umbrellas and although forty one were completed, we only have ten paired sets (where the audience member filled out an umbrella at the beginning and the end and handed them in together). Of these ten pairs, seven showed an increase in wellbeing (calculated by adding up the total ratings before the concert, the total ratings afterwards, finding the difference between the two scores and dividing this by the score before the session and multiplying it by one hundred). For two participants, this was by as much as 50%. Figure 1 shows these ten participants’ wellbeing before (in blue) and after the concert (in orange).

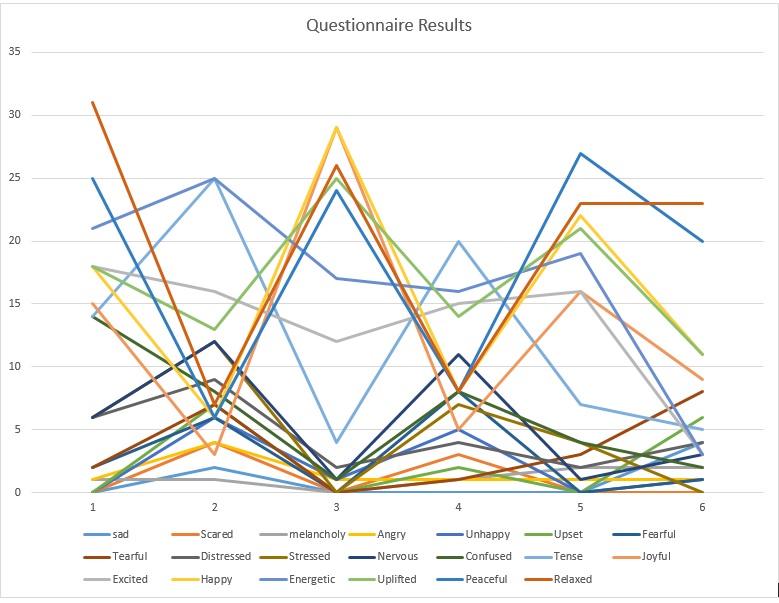

If we consider this data by state rather than by individual, we see that on average, participants reported feeling 34% more inspired, 26% more active, 5% more enthusiastic, 28% more excited and 5% happier after the concert than before. Only alertness showed a decrease – of 14%. This would seem to suggest that the concert did in general have a positive impact on wellbeing and this is reinforced by responses to the questionnaire, where ‘happy’, ‘relaxed’, ‘peaceful’, ‘uplifted’ uniformly top the graph (figure 2).

The questionnaire discloses some unexpected results though too, shown in figure 2. Each coloured line represents a different emotion or emotional state. Those that are capitalised were given as options on the questionnaire. Lower case adjectives were supplied by respondents. I discounted anything with a response rate lower than 6 as it made the graph too complex. On the vertical axis are numbers of responses, on the horizontal axis the number corresponds to the piece played. The order was:

- Claude Debussy Sonata for flute, viola and harp

- Yann Tiersen On the wire (for solo viola)

- S. Bach Sonata in G minor BWV 1020 for flute and harp

Interval

- Ravi Shankar L’aube enchantée for flute and harp

- Maurice Ravel Sonatine (transcribed from the original piano work) for flute, viola and harp

- Astor Piazzolla Oblivion (improvised by the ensemble)

There are some notable peaks and troughs. We can see that levels of relaxation begin quite high, at 31. They then rapidly decrease in the Tiersen piece to 7 and almost entirely recover during the Bach to 26. The dip in relaxation (and peacefulness, from 25 to 6) is matched by an increase in feeling ‘tense’ (up from 14 to 25) and ‘energetic’ (also 25). This probably reflects the fact that Tiersen’s piece was dramatic and accompanied by foot stomping and expressive facial expressions from David. Tense also gets a high response in piece four and this I cannot explain. One respondee raised an interesting issue: they had ticked tense, excited, energetic, stressed and unhappy in response to piece 2 but commented that they were ‘recognising an emotional tone in the music – e.g. melancholy or anger or exuberance – without actually feeling the corresponding emotion myself.’ So how many audience members were ticking emotions they associated with the music rather than ones they were feeling?

We can also see a relatively high number of audience members reported feeling confused and tense during the first piece of the music and this might have been related to the questionnaire itself and to the format of the event. Some commented that they felt confused because they didn’t understand the form and stressed ‘because I was not sure if we were still on piece one as I didn’t know the music at all’. Another commented that ‘I was very aware of having to decide on what emotions I was feeling. This meant I was very focused on the music & not as distracted by the specimens as I thought I might be.’

At the beginning of part two, the audience were treated to a short talk about music and the history of the emotions from Dr Marie Louise Herzfeld Schild. Participants reflected on how that knowledge affected emotional response in their comments. For example: ‘Knowing that the Ravi Shankar piece was themed on death meant that I thought about the specimens in the museum & imagined them interacting with the music’ and ‘I felt much more relaxed and able to engage emotionally with the music once I knew something about it cultural + historical context, in the second half.’ That knowledge of the music had enriched the experience was a recurring theme: ‘Having an awareness of the music helped to appreciate the musical pieces as well the environment in which they were played’; ‘the talk made me feel more aware + […] this resulted in feeling more alert and engaged. Felt that ‘knowing more’ resulted in subconscious labels and slightly lazier responses but this left me enjoying music more. Maybe’. This final comment raises an interesting question about the extent to which the audience had to ‘work’ in part one compared to part two and its impact on their enjoyment. While most of the quotations I’ve given suggest knowledge enhanced experience, this respondee suggests they may have been ‘lazier’ in the second half and are equivocal about whether information about the music improved the experience or not.

While 23 people didn’t respond to the question ‘How did your surroundings impact your feelings about/response to the music?’ at the end of the first half, and 29 didn’t respond at the end of the second, in general the museum did impact on audience responses to the music. While for one person: ‘There is a big contrast between the surrounding exhibited paintings and sample[s] and the peaceful-sounding music’ for another ‘I thought the venue would be more evocative and emotional that [sic] it actually ended up being – If anything it felt surprisingly mundane against the beauty and ethereality of the music.’ For many, the museum was a calm and relaxing space which helped them focus. Others were more unnerved though: ‘Eerie and haunting – effective. Made Piece 2 more impactful.’ Some also responded to the cultural capital afforded by the venue, noting, for example, ‘No real influence – just made feel really cultured’. An idea of the specimens as sentient participants was also invoked: ‘I also felt there was a second layer of audience, with the specimens participating and watching the event.’

There are a handful of other responses I’d like to draw out – consider for example, the respondee who explicitly demonstrates the impact of culture on our experience of a piece of music. In response to piece 4 they wrote: ‘As an Indian, it was a strange experience. I’ve never heard […] performed like this. It was like listening to someone speaking in Hindi with an English accent.’ One member of the audience experienced the music synasthetically and as well as ticking emotional states, wrote down the colours they associated with the pieces – something I had not anticipated. I also hadn’t expected the musicians’ facial expressions to be so important but this was mentioned several times in the comments and in discussion in the interval in terms of shaping emotional response.

I’d like to end on one of the most poetic responses which encapsulates what the event was trying to achieve – which this person has articulated perfectly: ‘I am left with a profound sense of the history of human feeling. The specimens are caught in a moment of time, and so were our emotional responses to this evening’s music. A wonderful way to experience a beautiful performance.’