Helen Stark is a project manager on the ‘Living with Feeling’ grant in the Centre for the History of the Emotions, QMUL. She has a book chapter on the man of feeling forthcoming in the edited collection Jean-Jacques Rousseau and British Romanticism.

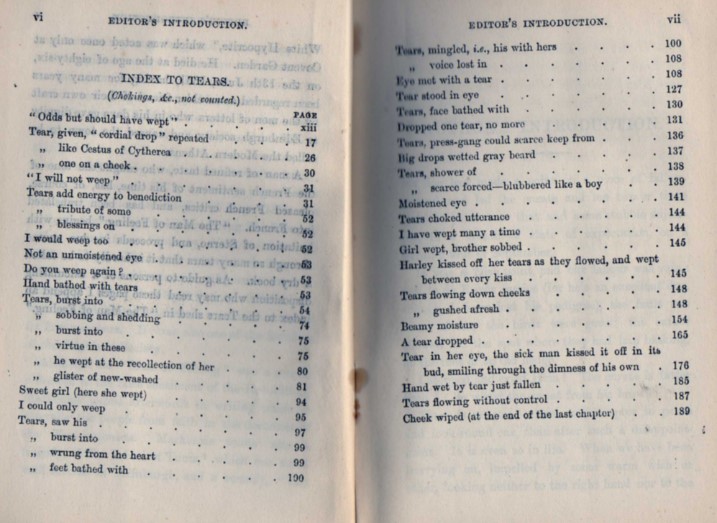

Avid readers of this blog might be familiar with Henry Mackenzie’s 1771 novel The Man of Feeling – as Thomas Dixon wrote in September last year, while in the eighteenth century Robert Burns could describe it ‘as a book I prize next to the Bible’, by the Victorian period it was being published with an ‘index of weeping’, mocking its tear-sodden narrative. So who was the man of feeling, and what provoked this change in his reception by British society?

The man of feeling is a character who emerges in literature of the mid-eighteenth century characterised by his sensibility: his sensitivity, heightened emotional state, charitable nature and proclivity for tears. As Walter Scott wrote in 1805:

It is no doubt true, that a man of sensibility will be deeply affected by what appears trifling to the rest of mankind; a scene of distress or of pleasure will make a deeper impression upon him than upon another; and it is precisely in this respect that he differs from the rest of mankind. [Walter Scott, ‘Godwin’s Fleetwood‘, The Miscellaneous Prose Works of Sir Walter Scott, 1835]

What marks the man of feeling, is his vulnerability to being marked. Scott explicitly identifies him as a different kind of man – one whose masculinity is implicitly not normal. Let’s see what this kind of behaviour looks like. On his way home from visiting London, Harley, Mackenzie’s titular protagonist, encounters a returning war veteran who turns out to have be Harley’s one-time neighbour, Edwards. Edwards relates his woeful life story to Harley and Harley responds with the characteristic (and later, much-mocked) tears: ‘The old man now paused a moment to take breath. He eyed Harley’s face; it was bathed with tears’. Edwards’ story includes an account of a gang turning up at his house and forcing his son to join the army (a practice called pressganging) and Harley’s response is, as we might expect, extreme: ‘At these words Harley started with a convulsive sort of motion, and grasping Edwards’s sword, drew it half out of the scabbard, with a look of the most frantic wildness.’ He reacts with an excessive, uncontrolled, unconscious physical response – seemingly he has overly empathised with Edwards’ tale. Later Harley and Edwards locate Edwards’ grandchildren whose parents are dead and visit the tomb of Edwards’ son, the children’s father:

“Here is it, grandfather,” said the boy. Edwards gazed upon it without uttering a word; the girl, who had only sighed before now, now wept outright: her brother sobbed, but he stifled his sobbing. […] The girl cried afresh; Harley kissed off her tears as they flowed, and wept between every kiss.

It is important to note that the two other male characters in this scene either withhold their emotion (Edwards) or manage to master it (his grandson). It is Harley and Edwards’ granddaughter who cry, implicitly casting Harley’s tears as feminine and out of kilter with the responses of other male characters.

In general, the man of feeling’s emotional responses isolate him from society. Consider for example, Goethe’s Werther, protagonist of The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774, rev 1787). Werther is in love with Lotte, who is engaged (and then married to) Albert. Returning from visiting the pastor together, Lotte ‘scolded me for my too passionate sympathies in everything and that it would be the end of me, that I should spare myself’. Lotte’s insight into Werther’s character warns of the problems the man of feeling faces; his sympathetic identification with others erodes the boundaries between them and she foreshadows his suicide with her warning ‘that it would be the end of me’. Her attempts to moderate his excess are fruitless: ‘She has reproached me for my excesses – oh, in such a lovable fashion! Excesses! That occasionally I may let a glass of wine become a bottle’ (p. 76). Werther wilfully misinterprets her comments; Lotte desires him to curtail more than his wine consumption and later begs him to:

be more moderate. Your intelligence, your knowledge, your talents, what manifold enjoyments they offer you! Be a man! Turn this sad attachment away from a woman who can do no more than feel sorry for you.

It is clear that Lotte considers Werther’s masculinity non-normative. His attachment to her demonstrates both an excess of inappropriate emotion and an inability to regulate his emotions and ultimately it unmans him. That she is policing his conduct demonstrates how William Reddy’s concept of an ‘emotional regime’ is manifested here. In The Navigation of Feeling (2001) Reddy argues that societies have a set of expectations about what constitutes normal emotional behaviour and how emotions should be expressed and that these are central to that society’s political regime. He defines it thus: ‘The set of normative emotions and the official rituals, practices, and emotives that express and inculcate them; a necessary underpinning of any stable political regime.’ There’s a conflict then between the kind of emotional response the man of feeling exhibits and the emotional regime of the society he is in.

Emotional regimes are not static and we see this change in what is considered normative emotion most clearly when we consider the reception of these novels. In The Great Cat Massacre (1984) Robert Darnton records the response of the Marquise de Polginac to reading Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Julie or the New Heloise:

I dare not tell you the effect it made on me. No, I was past weeping. A sharp pain convulsed me. My heart was crushed. […] My seizure became so strong that if I had not put the book away I would have been as ill as all those who attended the virtuous woman in her last moments.

Similarly, in 1771 the anonymous reviewer of The Man of Feeling in the Monthly Review claimed that ‘the Reader, who weeps not over some of the scenes it describes, has no sensibility of mind.’ There’s an implied criticism here of the reader who does not cry. Yet by the 1820s, Lady Louisa Stuart had found that the response to the novel had changed. Reading the novel with her friends: ‘Oh Dear! They laughed’. The man of feeling no longer elicited tears but instead laughter. Both his behaviour and the reader’s tearful response to it, represented a model of emotional response that was no longer recognised or understood in 1820s Britain. The decline in popularity of the man of feeling is normally attributed to the French Revolution and anxiety about the dangers of sensibility and associated revolutionary fervour spreading to Britain. But while this narrative accounts for a change from tears to fear, there doesn’t seem to be space in it for laughter.

This post is part of our ‘Normativity November’ series which explores the concept of the normal as we prepare for our exciting Being Human event ‘The Museum of the Normal’ tonight, 6pm-9pm.