Last week I was at a panel on mental health in India, at a conference in Goa organized by UCL. The speaker – Ratnaboli Ray, who runs a mental health NGO called Anjali in West Bengal – asked for anyone in the audience who’d ever had mental illness or been on psychiatric drugs to raise their hands. For a few seconds, no one did. And then about 15 of us did, in a room of around 100.

It felt strange to me, raising my hand, in a way I’m not sure it would anymore in the UK – it felt like I was risking my status, pushing against a wall of shame and secrecy. In fact, I only raised my hand because the lady next to me did first.

This is the paradox: that a culture with such a huge focus on health, well-being and spiritual wisdom should see mental illness as so taboo. If Prince Siddhartha hadn’t had a breakdown, India would have never given the world Buddhism, yet this is a country where mental illness is simply not discussed.

Why? My tentative initial answer is that India (like the UK) is a country obsessed with status and hierarchy. Mental illness is still seen as a terrible blot on one’s status, and therefore a risk to one’s career advancement, one’s marriage prospects, one’s place on the social scale, and above all to your family’s social prospects.

It’s also a threat to your rights. If you’re diagnosed with a mental illness, it can affect your ability to open a bank account, to get a driving license, to maintain custody of your children. Until 1976, it was accepted as grounds for divorce.

To protect the family status, the mentally ill are often abandoned in over-crowded psychiatric care facilities, where they can be ‘treated worse than animals’, according to a report by Human Rights Watch.

Mental illness is also hiding in plain sight in India. According to two recent surveys, between 130 million and 150 million Indians are suffering from a mental illness, including depression, anxiety and substance abuse. I’ve met successful young Indians on my travels who are clearly stressed, over-worked, and in need of help. But mental illness is seen as a terrible curse, not something that pretty much happens to everyone in varying degrees of intensity.

As the Buddha put it, life is suffering – having a mind means you sometimes experience mental distress, and there are techniques we can learn to mitigate that, both psychological and pharmaceutical. Indeed, Buddhism is one of the major influences on Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, which the NHS has put over one billion pounds into providing.

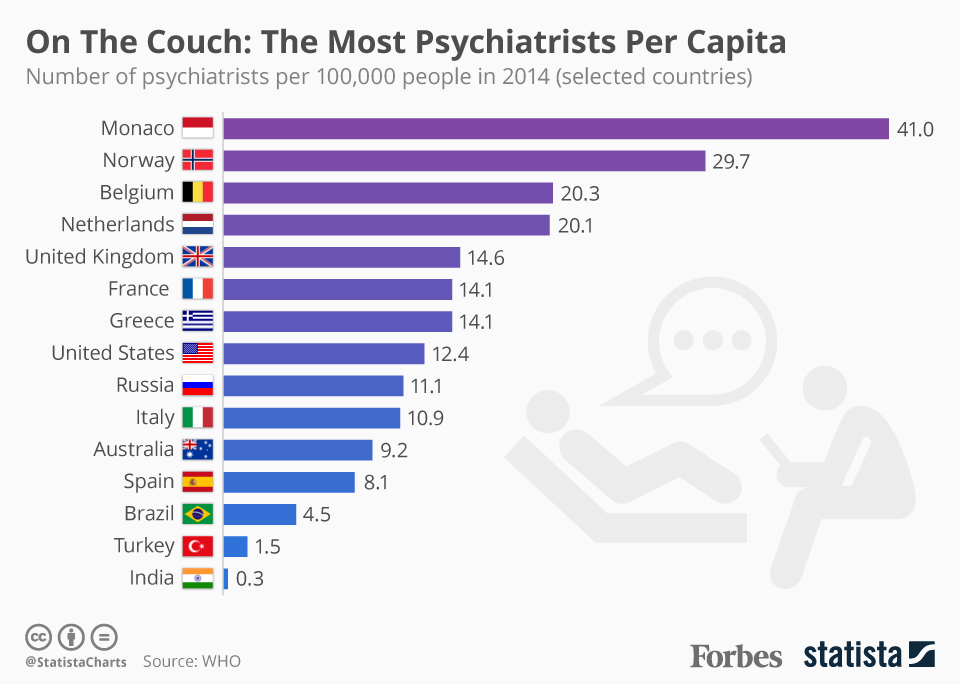

Yet in India, 90% of those with mental illness receive no treatment at all. India has 0.3 psychiatrists per 100,000, one of the lowest figures in the world. And they’re almost entirely in big cities. (Here’s a graph about that:)

Even among the urban affluent, very few seek therapy because of the stigma attached. I sat next to one lady on a plane and said I wrote about mental health. She told me of her ex-husband, who refused to admit he had depression. I didn’t like to ask if they had divorced or he was one of the 250,000 Indians who kill themselves each year.

Soumitra Pathare, an academic who drafted a new Mental Health Act, says: ‘There is institutionalized discrimination against the mentally ill. If they were a caste or women, we would be doing something for them, but we do nothing.’

Things are finally beginning to change. The new Mental Health Act is due to be made law this parliament, and will legally guarantee Indians’ right to treatment, and also to refuse treatment if they don’t want it (many inmates are in asylums and given Electro-Shock Therapy without consent). There are new initiatives to train community health workers to give brief psychological therapies.

There are several new apps and websites that offer counseling and therapy online. In Chennai, India’s third biggest city, I saw adverts for private counsellors and a wall painted with a big sign: Depression Is Treatable. There’s even a sex therapist in Bangalore (something so unusual it was written up in the media).

There are signs of a new openness around mental illness and wellbeing – last year, there was even a Bollywood film, Dear Zindagi, about a young woman seeking therapy for depression from a kindly therapist. Imagine if one of India’s cricket superheroes opened up about mental illness – something several western sports stars have begun to do.

At the UCL conference, I spoke to Vikram Patel, a Wellcome-funded psychiatrist from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who has pioneered training rural community care workers in the delivery of brief psychological therapies, who was voted one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people in the world (he points out the leader of Boko Haram is also on the list).

Why are there so few psychiatrists in India?

There’s a bottleneck problem in training – only accredited teachers can train new psychiatrists and there are very few accredited teachers. There’s also a stigma around being a psychiatrist, compared to say a neuroscientist. And there’s a huge distribution problem too – most psychiatrists work privately in big cities. In rural India, there could be a region with 10 million inhabitants and no psychiatrists.

Your approach is to train community ‘health visitors’ to give brief therapy?

Yes, we’ve trained health workers to give specific treatments for specific conditions. We found it worked very well when they were trained just for that, in controlled conditions. We now need to see how it works out in the field, in frontline primary care, where health workers treat not just mental but physical illness. The treatment of both in fact uses similar skills – lifestyle support, behavioural change support, the promotion of self-care.

And they give similar sorts of psychological therapies to western psychotherapy? Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, interpersonal counseling etc?

Yes, similar therapies, but briefer and simpler. The most profound discovery for me is that the theory of psychological mechanisms is universal. Cultural factors play a role in the metaphors you might use. Say you train people to use meditation and yoga in the treatment of anxiety. You could train them to breathe in, and then breathe out saying ‘om’, or a prayer to Jesus if they’re Christian. Those cultural factors make a difference because you’re tapping into hope, which is a very powerful healer.

Is depression and anxiety treated here?

Hardly at all. I thought the ‘worried well’ was a Western phenomenon but it exists here too. The majority could recover with some form of self-care, but some need more clinical interventions. But depression and anxiety are not even seen as illnesses. It’s just your social situation. It gets somatized, as fatigue or insomnia for example. And doctors would also not recognize they’re actually treating depression, they would treat it with painkillers or sleeping pills. People criticize me for medicalizing people’s experience, but these people are already in clinics, they’re just not getting the right treatment.

So nothing like the NHS’ psychotherapy service exists here?

Nothing remotely like it. We recently published a trial of psychotherapy in the Lancet- that was the first ever trial of psychotherapy in India. We don’t want to repeat the mistakes of the NHS’ therapy service, which was too professionalized. We want more self-care and community care – my dream is to be able to train someone off the street to treat someone else for depression.

Do you think computerized-CBT apps could be a way of getting therapy to more people?

Yes, I’m bullish on technology, it will transform healthcare in general. But there are limits on access to the internet, particularly for the poor and women. But we’re beginning to see things like Facebook pages for people with schizophrenia.

Are there charities and NGOs lobbying for improved mental healthcare?

There are, but they’re small, very local, and not yet working effectively together in the way we’ve seen, for example, in the treatment of HIV.

Could online media – blogs etc – play a role in opening up the conversation and getting rid of stigma?

Definitely. In fact, we’re launching a website in April which will encourage people to share their experiences online through various social media. You can watch Vikram’s TED talk online.