This is a guest post by Dr Åsa Jansson, an associate member of the Centre for the History of the Emotions. Her research explores the history of “disordered” or “pathological” emotions since the 1800s, and the different ways in which modern medicine has tried to label and categorise our emotions as normal or deviant in different contexts. For more details about Åsa’s research, including publications, please see her Academia page.

This is a guest post by Dr Åsa Jansson, an associate member of the Centre for the History of the Emotions. Her research explores the history of “disordered” or “pathological” emotions since the 1800s, and the different ways in which modern medicine has tried to label and categorise our emotions as normal or deviant in different contexts. For more details about Åsa’s research, including publications, please see her Academia page.

“We seem to be scared of sadness as a society, we’re always running away from it. I think we need to stop running and instead face up to and even embrace sadness. It’s a big part of being human and I think it’s at the heart of compassion.” Steve Todd, organiser of London SadFest

Why do we love sad films? What is it about sitting in a dark cinema (or in front of the TV at home) crying your eyes out that’s so appealing? Isn’t sadness supposed to be a negative emotion, especially in contemporary society? In many ways, contemporary cultural messages seem to tell us to avoid sadness at all costs, that happiness is both the ultimate life goal and an individual choice.[i] Happiness has even become a political objective: in 2011 the government rolled out the Happiness Survey (formally entitled ‘personal well-being in the UK’) in an attempt to measure how happy the British public are.

However, as Rhodri Hayward noted when the first results of the survey were published in 2013, the government’s focus on ‘individual’ happiness at a time of growing inequality and job insecurity highlights a fundamental division in contemporary British politics between a rights-based approach to well-being and one that focuses on internal emotional states.

Another problem with the twenty-first century preoccupation with the pursuit of happiness is that sadness is, of course, unavoidable. There are times when we will feel sad, despite our best efforts to be happy. However, the way in which we’re drawn to artistic representations of sadness suggests that this emotion is not only unavoidable, but at times desirable. So, can sadness be a positive emotion? Can it be enjoyable? Useful?

These are some of the questions that inspired London SadFest, a film festival that explores and celebrates sadness on the big screen. The festival runs over three days, March 3-5, at the Genesis Cinema in Mile End, and brings together scholars, poets, artists, and, of course, sad films.

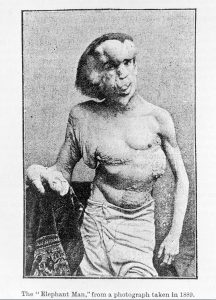

Each film screening is followed by a short talk and discussion around some of the themes invoked by the film. The festival kicks off on the Friday evening with a viewing of David Lynch’s classic film The Elephant Man, which is based on the true story of Victorian ‘freak’ Joseph Merrick (called John in the film). Merrick’s story deals with themes that resonate with most of us: loneliness, compassion, fear, and the desire to belong.

Joseph Merrick, also known as ‘the Elephant Man’ in 1898. British Medical Journal. Credit Wellcome Library, London

After the film I will briefly speak to the audience about sadness in relation to one of the film’s central themes, compassion. The Elephant Man asks us to feel empathy toward the film’s protagonist – to feel with him, not just for him. We are invited to recognise our own humanity in this visually monstrous figure, to see him not just as our equal but as our potential self. The idea of compassionate sadness suggests that sadness has important uses as a basis for social relations. I will explore the question of useful sadness within the context of the history of sadness and melancholy in modern Britain, inviting the audience to consider whether the twenty-first century pursuit of happiness and our growing aversion to sadness prevent us also from feeling compassionate sadness, the kind of sadness that inspires us see past that which divides us and reach out to our fellow human beings.

After the talk, the audience can proceed to drown their sorrows at the bar, which will also host a number of live performances on the sadness theme.

The theme of the second day is ‘love, friendship and vulnerability’, with screenings of Ken Loach’s Kes (1969) and Kar Wai’s In the Mood for Love (2000), as well as more performances. Kes is followed by a talk by Sarbijt Samra, who will be speaking to the audience about some of the issues highlighted by the film. Sarbijt’s talk will suggest that the authenticity of Kes comes from the fact that the film doesn’t compromise. Rather, it faces head on difficult questions about social class that are at least as relevant today as when the film was first released – if not more so.

The final day of London SadFest continues to explore sadness, through ‘tragic decisions and historical forces’. The first screening is of Pakula’s 1983 film Sophie’s Choice, after which literature and drama scholar Jennifer Wallace will invite the audience to think about what constitutes a ‘tragic film’. Traditionally, since the ancient Greeks, tragedy has been thought to be the province of the theatre. But can we speak about a tragic film? And how would we define it? Jennifer Wallace offers a whistle-stop tour through some essentials of tragedy – choice, recognition, pity and fear, fate, catharsis – guide our assessment of ‘sad’ films.

The festival closes with Lee Daniels’ Precious (2009), which will be introduced by Marcia Harris. Marcia will discuss some of the issues that made the film controversial when it was released, and which divided critical opinion. Marcia has a background in child psychology and community work and holds a core belief that agency and power, especially a child’s, grows strongest when nurtured from within, rather than bestowed upon us by acts of benevolence.

London SadFest will be a weekend full of emotion, but it also promises to be a thought-provoking event. The tensions, or contradictions, in how sadness is perceived and experienced are not specific to our time period. For instance, Erin Sullivan has highlighted the complex place of sadness in Shakespeare’s England, suggesting that:

“No passion was believed to harm the body more than sadness – according to contemporary mortality records it was responsible for more deaths than all the other passions combined – and yet none was linked so consistently with spiritual repentance and conversion”.[ii]

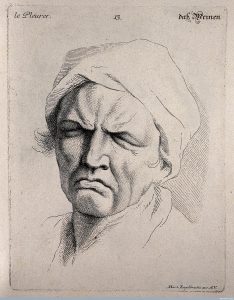

A woman’s face expressing sadness. Engraving by M. Engelbrecht (?), 1732, after C. Le Brun. 1732. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

This contrast between sadness as harmful and sadness as useful might resonate with current ideas about sadness as pathology versus sadness as cathartic (e.g. watching a sad film and “having a good cry”), but Sullivan’s remark also speaks to view of the emotions that holds these to be historical events. Emotions take different forms and have different cultural significance in different time periods, and some emotions disappear entirely, while new ones emerge. The sadness of Early Modern England is not the sadness of twenty-first century society – for instance, sadness is not considered a common or barely even possible cause of death today. To the question of whether sadness is useful or harmful, then, we must also add the question of whether it’s a universal emotion.

If you’re curious about the place of sadness in contemporary (and historical) society, or if you simply enjoy sad films, come along to London SadFest. Just don’t forget to bring tissues!

Tickets for London SadFest are on sale now. You can read more about the festival and book your tickets here on their website.

[i] E.g. http://www.marcandangel.com/2012/03/01/10-ways-happy-people-choose-happiness/; http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/12/09/scientific-proof-that-you_n_4384433.html

[ii] Erin Sullivan, Beyond Melancholy: Sadness and Selfhood in Renaissance England, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2016, p. 14.