Louise Klinke Øhrstrøm is a Danish author and translator. She has translated Julian of Norwich’s Revelations of Divine Love from Middle English into Danish (Boedal, 2010) and studied Julian’s texts at University of East Anglia (2011-2013).

Many readers may know the 14th-century-mystic and writer Julian of Norwich’s famous words from Revelations of Divine Love: “All shall be well”. Julian also phrases this notion another way: “and so schalle all schame turn in to wyrschyppe” (ST 758). Throughout her writings, she shows particular interest in what the emotion – or state – of shame does to man.

Although the word ‘shame’ only appears a few times in Revelations of Divine Love, a close reading of the figurative language of both the short and the long text suggests that shame is a key motif in Julian of Norwich’s literary work and in her theology. Exploring the ways in which Julian explicitly uses the words ‘shame’, ‘ashamed’ and ‘shameful’ in similar but also, at times, acutely different fashions, reveals that shame is presented as a complex and hybrid concept in Revelations of Divine Love. On the one hand, shame is described as a necessary part of accepting one’s guilt of falling into sin, which is “shameful” (LT 573). The sight of our sins is supposed to make us “ashamd of our selfe” (ST 619), recognising the “grete shame…[that we have] defoulyd the fair ymage of god” (LT 561). On the other hand, Julian underlines that there is no reason to be ashamed of our sins because God is able to turn any sin into worship, just like he did with biblical characters such as David, Maria Magdalena, Peter and Paulus who “are knowen in the Church in erth with her synnes, & it is to hem no schame, but is turnyd hem to worship” (LT 561). Julian repeats this point in several ways in Revelations of Divine Love such as “syn is na schame bot wiscippe to mann” (ST 756) and “ffor I saw full sekirly, that ever as our contrarioust werkyth to us here in erth peyne, shame and sorow ryth so on the contrariewise grace werkyth to us in hevyn, solace, worship & bliss” (LT 574).

According to Julian, we can look at ourselves in two ways, a higher and lower ‘beholding’. The higher makes us dismiss shame, while the lower encourages shame: “ffor the heyer beholding kepith us in Gostly solace & trew enjoying in God. That other that is the lower beholding kepith us in drede & makith us ashamyd of our selfe” (ST 623). Julian also states that the way in which God will transform sin into worship will leave all shame with the devil in the end: “for all that god sufferith him to doe turnith us to joye, & him to shame & wo” (LT 534). Thus Revelations of Divine Love Showing of Love presents a number of understandings of shame, which Julian touches explicitly on by using the word ‘shame’.

However, it is through the figurative language in Showing of Love that Julian’s complex theorising of shame really unfolds and becomes a key motif in the texts. By using figures of speech such as metaphors, similes, allegories, parables, symbols, metonymies, examples and personifications, Julian performs shame in a literary way which engages the reader much more significantly than in the passages where ‘shame’ is explicitly mentioned.

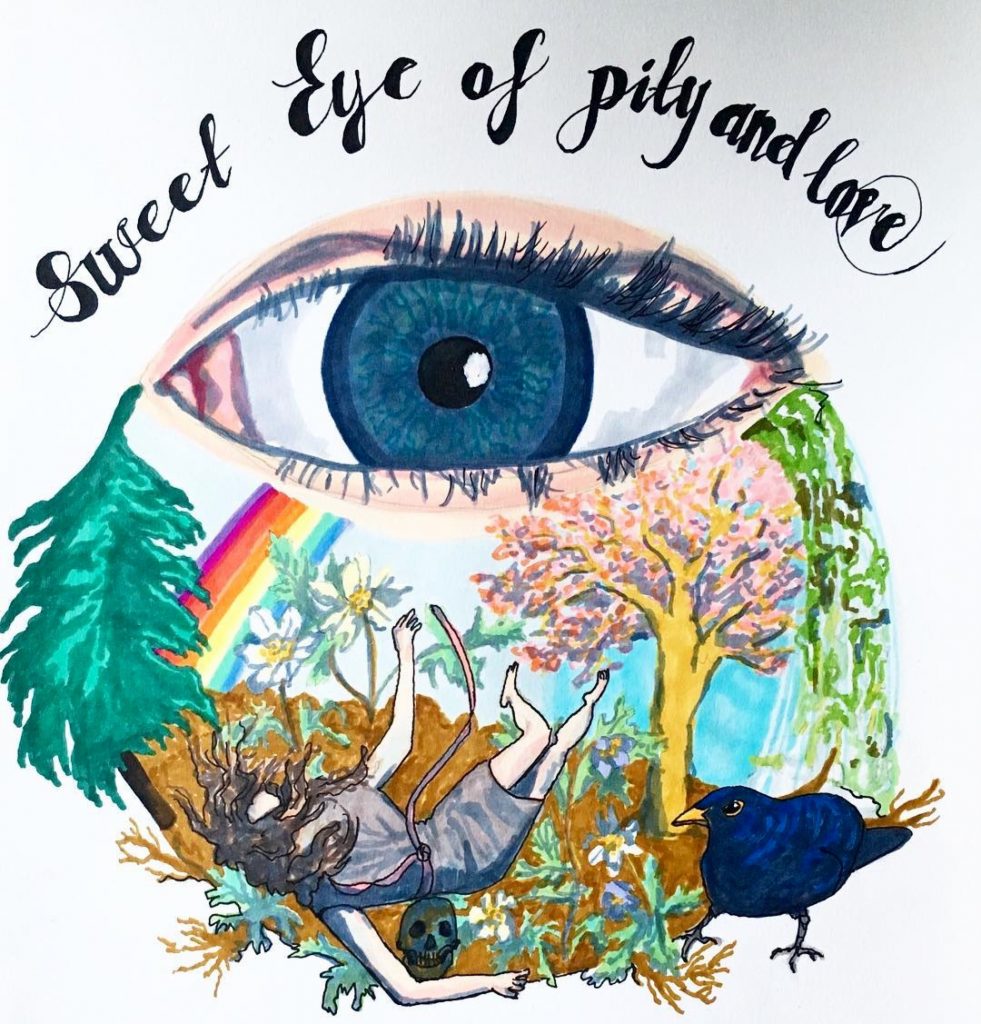

The key metaphor when it comes to shame is “gastelye blyndehede” (ST 774), which Julian examines in many ways throughout Revelations of Divine Love. Julian mainly uses this metaphor for a condition where man is too ashamed to see God and thus cannot recognise his own worth as a loved creature. She also uses the metaphor to stress that shame can blind human beings in a way that hinders self-acceptance and blurs a clear understanding of life and other people. Mist is used as a simile that expresses this losing of sight too. According to Julian, “it makith as it were a thick myst aforne the eye of the soule” when we occupy ourselves too much with other people’s sins which results in that “we may not for the tyme se the fairehede of God” (LT 617).

Knowing that Revelations of Divine Love is based on a number of visions, it is not surprising that the contradiction of ‘being able to see’ and ‘being blind’ is important to Julian, and using these physical senses in a figurative way is clearly inspired by the New Testament where Jesus describes the Pharisees as “blind leaders of the blind” (Matthew 15:14) and “blind guides” (Matthew 23:15). However, the interesting point about Julian’s metaphor of “gastelye blyndehede” is that she uses it in a slightly different way than it is used in the New Testament. When Jesus criticises the Pharisees for being spiritually blind, he is criticising their focus on superficial rituals and material matters. Accusing them of having been blinded by pride, Jesus says: “Thou blind Pharisee, cleanse first that which is within the cup and platter, that the outside of them may be clean also.” (Matthew 23:25-27). While Julian also stresses that spiritual blindness implies delusions and is the main barrier between man and God, her focus is not on how pride blinds man, but on how shame blinds man.

Stating that “man is blindid in this life” (LT 580), and that “the blindnes that we have is of Adam” (LT 582), Julian refers to the shame that Adam and Eve felt in Eden after having eaten of the forbidden fruit. According to Julian, this shame still torments human beings; “we falyn ageyn into blindhede”, and we “arn made derke & so blinde that onethys we can taken ony comfort” (LT 585). She also uses “Adams old Kirtle” (LT 584) as a symbol of that shame and contrasts it to “the larghede of his [God’s] clotthyng” (LT 580) and the metaphor that God “is our clotheing that for love wrappith us, halseth us, & all beclosyth us for tender love – that hee may never leave us” (LT 519). Shame is, in other words, something which represents us, just like clothes do, but also something that we, potentially, can take off and ask God to replace with something better.

Both images, shame as spiritual blindness and shame as an old tunic, we find in The Parable of the Lord and the Servant in chapter 51 of the long text, which Julian presents as an essential part of Revelations of Divine Love by comparing it to an ABC when it comes to understanding God: “in this mervelous Example I have techyng with me as it were the begynnyng of an ABC where by I may have sum Vnderstondyng of our Lodis menyng” (LT 583). The parable shares similarities with the parable of the prodigal son from the Gospel of Luke chapter 15. A servant stands before his lord and is sent on a certain mission. Eager to please his lord, the servant not only walks but runs to fulfil the mission. Consequently, the servant falls in a slough and cannot get up. He “gronith & monith & walith, & writhith but he ne may rysen ne helpen hymself be no manner wey” (LT 577). The servant is in great despair. His tunic is dirty and torn apart. His body is heavy. He cannot turn his gaze to his lord.

In the following chapters, Julian interprets the servant as being Adam and as being Christ. Reading the servant as Adam, Julian implies that the servant’s agony and turning away is similar to Adam’s hiding in shame in the Garden of Eden. By emphasising that Adam is in all men, she also suggests that the human condition is this blindness and turning away from God in shame. When interpreting the servant as being Christ, she emphasises that Christ always had his gaze on the lord and adds another section to the parable where Christ is risen up from the slough, and where his dirty tunic is replaced with a white and shiny one. By stating that “we have in us our Lord Jesus uprysen, we have in us pe wretchidnes & pe mischefe of Adams ffallyng deyand” (LT 585), Julian concludes that we also have the potential to rise from our shame and have our dirty tunic replaced by a white one. In the long text, she uses several other metaphors to explain the key steps towards this transformation: We are to accept that we need “helyng” (LT 619) from our spiritual blindness, to receive compassion from our “Moder Criste” (LT 595) and to realise that “we be his Corone” (LT 584) and that “he made mans soule to ben his owen cyte” (LT 580).

Thus you could argue that Julian actually understands salvation as a process of discerning shame, recognising the fall (and the “constructive” shame) while rejecting the feeling of unworthiness (the “destructive” shame) and rising in dignity. Although Julian wrote her texts more than 600 years ago, this approach to shame seems rather modern and relevant in the context of recent shame studies that discuss the social functions of shame while paying attention to the way in which shame can also be “blinding”

***

ST (Short Text): The Amherst manuscript, BL Additional 37790, British Library, London

LT (Long Text): The MS Sloane 2499 manuscript, British Library, London

Edition: Julian of Norwich, Showing of love: Extant Texts and Translation, ed. by Sr. Anna Maria Reynolds and Julia Bolton Holloway (Firenze: Sismel, 2001)