Dr Hetta Howes is a Lecturer in English at City University. After studying for her BA and  MPhil at the University of Cambridge, she joined Queen Mary in 2012 to begin her doctoral thesis on the role of water as a literary metaphor in late-medieval devotional prose, currently being turned into a monograph: Transforming Waters in Medieval Devotional Literature. She is one of the BBC/AHRC New Generation Thinkers for 2017/18 and is committed to communicating her research to a wider audience.

MPhil at the University of Cambridge, she joined Queen Mary in 2012 to begin her doctoral thesis on the role of water as a literary metaphor in late-medieval devotional prose, currently being turned into a monograph: Transforming Waters in Medieval Devotional Literature. She is one of the BBC/AHRC New Generation Thinkers for 2017/18 and is committed to communicating her research to a wider audience.

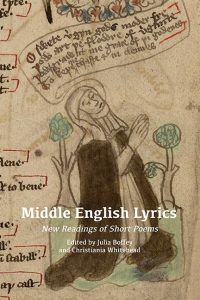

Lyrics crop up everywhere in medieval manuscripts, whether they are compiled as part of a verse collection or scribbled on spare leaves, crammed into the space between prose works and prayers. The forthcoming essay collection Middle English Lyrics: New Readings of Short Poems (edited by Julia Boffey and Christiania Whitehead) showcases the variety of forms and functions of medieval lyrics, from biblical paraphrases to lyric interventions in Chaucer. My own contribution to this volume spotlights a short lyric written by the Franciscan friar William Herebert in the fourteenth century. In it, I’m particularly interested in exploring the emotional side of lyrics. To put it another way, I’m interested in how medieval lyrics might teach their readers how to feel.

Unknown Artist, ‘Minstrels with a Rebec and a Lute’,

13th Century, Manasseh Codex, El Escorial, Madrid

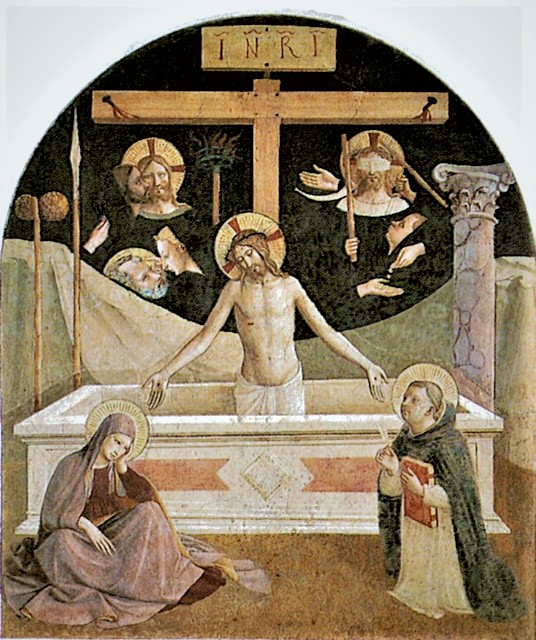

The later Middle Ages saw a craze for a new kind of text: the Passion meditation. (I have previously written for this blog about the connection between Passion meditations, women and water). These guided meditations not only describe events from Christ’s life, Passion and death but ask the reader to imagine themselves as either a witness or active participant in those events. So the reader is encouraged to imagine watching Christ being flogged, or struggling with the heavy load of the cross as the crowds taunt and jeer him. But they may also be urged to become a part of the action; to go and wipe Christ’s brow, or to wash and kiss his feet. Moreover, they’re encouraged to feel a myriad of emotions – awe, dread, pity, shame, sorrow. In this way, a more personal, intimate and emotional relationship with Christ is fostered. Whilst these Passion meditations are usually found in prose works of spiritual guidance (often, if not exclusively, targeted at women) the techniques of the genre can also be seen at work in medieval art – evocative images of a bleeding, suffering Christ – and in other forms of writing, such as medieval lyrics.

Fra Angelico and Assistants, ‘Meditation on the Passion, The Man of Sorrows with

Instruments of the Passion with the Blessed Virgin Mary and Saint Thomas Aquinas’, Italian, c.1441-1442, Florence, Convent of San Marco

In a fifteenth-century carol the narrator, who remains unmoved by scenes from Christ’s Passion, hears a woman weeping. He quickly discovers that she is, in fact, the Virgin Mary. Seeing her tears of grief he tells her that he cannot cry, for he is so ‘harde hartid’ (hard-hearted). She continues to weep, saying that nature must ‘move’ him, and by the end of the lyric the narrator is weeping himself, his heart softened by his interaction with Christ’s grieving mother. ‘Who cannot wepe come lerne at me’ is Mary’s repeated refrain. With it, she teaches not only the fictional narrator but also whoever might be reading or listening to the carol to soften their hearts, to allow Christ’s suffering to permeate. In this way, the lyric acts as a kind of ‘affective script’ (a phrase coined by Sarah McNamer, and which you can read more about here: https://emotionsblog.history.qmul.ac.uk/2015/12/sarah-mcnamer-on-affective-scripts-in-sacred-and-secular-literature/).

William Herebert’s biblical paraphrase of Isaiah, Quis est iste qui uenit de Edom? (Who is it that comes from Edom?), predates both this late-medieval carol and the craze for Passion meditations in the later Middle Ages. However, Herebert’s small but careful additions to his biblical source suggest that he is aiming not only to transform the Bible passages into verse but to use them to create a similarly affective script. His lyric is not only tailored to produce a particular emotional response in the reader but ultimately to help them convert that initial emotional response into a more productive, devotional state. The emotion? Shame. The devotion? Contrition and penitence.

The lyric is framed in the manuscript as a dialogue between a group of angels and the solitary figure of Christ, a doughty knight who enters the scene fresh from battle with blood-red garments, just like those worn by the treaders of a winepress. On the surface, the lyric seems to be engaged with the Old Testament idea of Christ-the-warrior, rather than the New Testament Christ, who suffers at the hands of his tormentors. However, whilst Herebert does stay close to his source (Isaiah 63:1-7), he also makes a number of embellishments which allude to the Passion, and introduce the idea of shame. He inserts a number of bloody details, noting the ‘grisliche’ (grisly) nature of Christ’s clothing. He emphasises Christ’s solitude after the ‘battle’ he has fought, reminding us that many witnessed it but no one went to help – and in doing so he recalls Christ’s metaphorical battle during the Passion, for the redemption of mankind, which he fought alone.

Alongside these bloody additions, Herebert also amplifies the emotion of shame, which is only hinted at in the original biblical verses. The dialogue format of the lyric, between Christ and the angels, forces the reader or listener into the role of bystander. Medieval Christianity taught that by suffering the Passion, Christ redeemed the sins of all Christians – the sins of those living afterwards, not just of those living before. Many medieval texts, therefore, imagine the everyday sins of medieval Christians rewounding, or even recrucifying Christ, long after the historical event itself. The reader’s role in Herebert’s lyric is to stand by and watch the action unfold – there is no opportunity to imagine running to Christ’s aid, to involve themselves in a way that might alleviate their own shame in bringing about the Passion through their sins. They must stand, watch, and feel the full force of their emotion.

However, it’s not all doom and gloom. The final lines of the lyric encourage the reader to move on from their emotional shame and to convert it into something more productive:

‘On Godes milsfulnesse mercifulness

Ich wole by-thenche me, I will bethink me

And herien Him in alle thing and praise; everything

that He yeldeth me.’ grants

Reader/listeners are prompted to feel shame. Crucially, however, they are also prompted by the final lines to pursue a proper outlet for this emotion, one that is scripted for them by the penitential Jews: mindfulness of Christ, his victories and his sufferings, followed by contrition and penitence. The emotion must come first: it is the catalyst. But the emotion shouldn’t be wallowed in; the reader shouldn’t become ‘adreynt in shennesse’ (drowned in shame) but should use their emotion to propel constructive devotional practice.

Paying attention to lyrics such as Herebert’s Quis est iste qui uenit de Edom can help to reveal just how aware of emotion, and its devotional potential, medieval authors actually were. Herebert recognises the importance of shame, as a catalyst for devotion, whilst remaining alive to the fact that wallowing in that emotion might metaphorically drown a reader. He artfully elicits emotion in his reader, whilst also encouraging them to put that emotion to good use by encouraging a reflection on sin in both personal prayer and confession. In his rendering of this popular biblical verse, Herebert, therefore, doesn’t just teach his reader what to feel, but also how to feel.

Middle English Lyrics: New Readings of Short Poems, ed. Whitehead and Boffey (Cambridge: forthcoming September 2018)

My essay, and the lyric itself, can be found in ‘‘Adreynt in shennesse’: Blood, shame and contrition in Quis est iste qui uenit de Edom?’ is forthcoming in Middle English Lyrics: New Readings of Short Poems, ed. Christiania Whitehead and Julia Boffey (Cambridge: Boydell and Brewer; forthcoming September 2018). The lyric can also be found in The Works of William Herebert, ed. S. R. Reimer (Toronto, 1987), p. 132, no. 16