Today marks the 200th anniversary of the sensational trial of Queen Caroline for adultery. In this guest post for the History of Emotions blog, Dr Matthew Roberts of Sheffield Hallam University looks at the wave of sentimentalism the scandal created, and how British radicals such as Richard Carlile crafted a politics of feeling in response.

Two hundred years ago today, one of the most talked about trials in British history began in the House of Lords. Under the terms of the aptly named Bill of Pains and Penalties, Queen Caroline – the estranged wife of the new king, George IV – was put on trial for adultery. This was demanded by the king who wanted to prevent Caroline from becoming queen with the hope that a guilty verdict would be grounds for divorce.

The Trial of Queen Caroline, 1820, by Sir George Hayter. Source: National Portrait Gallery, licensed under Creative Commons.

Just as royal scandals are today, the Queen Caroline affair was followed closely by virtually the whole country, with public opinion firmly behind the queen. The new king was widely reviled. By contrast, Caroline was loved by the people, whose just cause, in William Hazlitt’s words, ‘struck its roots into the heart of the nation’.[i] As Hazlitt’s words imply, the affair was the occasion for a wave of sentimentalism. The wave was big, even by Georgian standards.

When Caroline returned to Britain in June 1820 a constitutional crisis ensued which pitted the king and his ministers against parliament and the people. Feelings ran high both inside and outside of parliament. The affair was discussed in a highly melodramatic register, in which the wronged and not too virtuous queen was presented as the victim of a loveless marriage. The young dissolute, libertine and already (illegally) married Prince of Wales had consented to the marriage back in 1795 only as a quid pro quo for parliament paying off his massive debts.[ii]

Relations between the two royals deteriorated almost immediately, with Caroline forced into exile in 1814. By all accounts, the queen had led a lively life, mainly in Italy where, it was rumoured, she had taken an Italian lover, Bartolomeo Pergami.

Leading the campaign outdoors in favour of the queen were the radicals who skilfully presented Caroline’s suffering as a synecdoche for the plight of the working classes. Feeling was the plane upon which queen and people met. As the people of Nottingham declared to her: ‘The addressers felt for the wrongs of the Queen as they felt for the various oppressions under which they themselves laboured.’[iii]

Plebeian women sympathised with Caroline as a victimised wife; many suffered with the queen.[iv] Respectable ‘men of feeling’ felt the chivalric urge to protect their queen.[v] Those who did not sympathise with the queen were callous. The crowds who took to the streets, especially in London, admired the queen’s courage in returning to Britain despite huge bribes and threats, and were prone to angry outbursts and rioting when provoked by the authorities as they frequently were in the febrile months which followed.

Bronze medal commemorating Queen Caroline’s arrival in Britain, by J. Westwood, 1820. Source: Author’s personal collection.

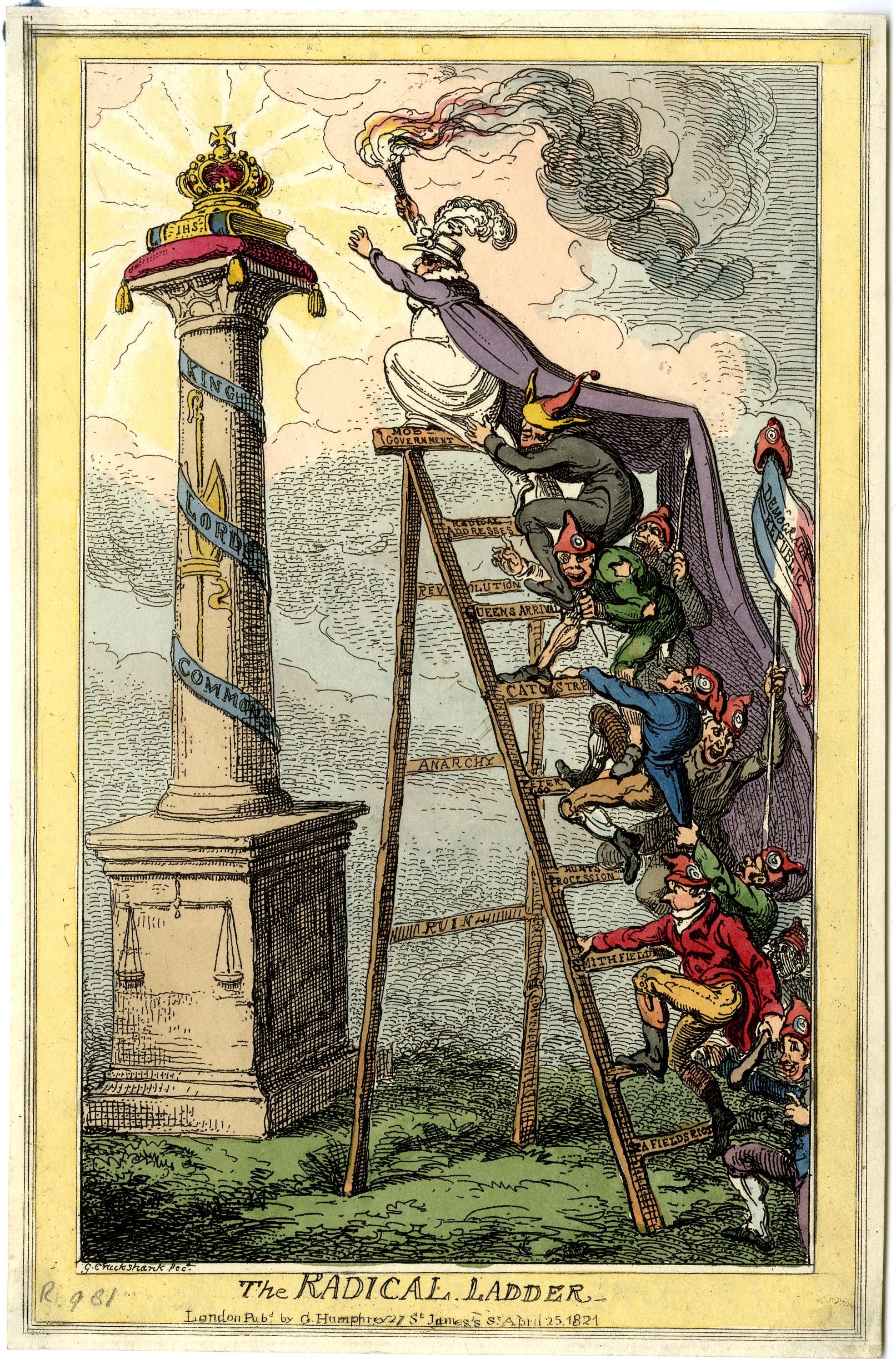

The authorities and their loyalist supporters were anxious and fearful, for behind the apparent radical displays of loyal disloyalty which attached itself to the coattails of the queen lurked the Jacobin threat of bloodthirsty revolutionaries, fears that had been stoked by Peterloo and the recently foiled Cato Street conspiracy. It was hatred for the king rather than love for the queen which motivated the radicals, cynics claimed. As a result, the queen was playing with fire in allying with the radicals. Fire and smoke were recurring motifs in anti-radical and pro-king caricatures, visual representations of the inflamed passions of the multitude stoked by radical leaders.

The Radical Ladder, by George Cruikshank, 1821. Source: British Museum, licensed under Creative Commons.

Satirists had a field day as caricatures, pamphlets, broadsides and squibs circulated widely. Some of this print and visual culture was bawdy and semi-pornographic, designed to shock as well as amuse, in its lampooning of the debauched king or the queen’s lewd continental lifestyle, complete with xenophobic hostility to Caroline’s foreign lovers.

Among those radical supporters of the queen was the unlikely figure of Richard Carlile. As a republican he had, initially, dismissed the queen’s case as humbug, but he soon changed his tune to the extent that he, too, found it impossible to resist being sentimental: ‘an involuntary tear has oft trickled down my cheeks on reading of your cause’, he told the queen from his prison cell in Dorchester gaol where Carlile was serving a long prison sentence for blasphemy.[vi] Carlile’s wife, Jane, took over their radical publishing business and bookshop in Fleet Street, and she published a number of squibs and pamphlets in support of ‘the ill-fated, ill-married and ill-treated Caroline’.[vii]

In the aftermath of the affair, there is no doubt that Carlile set about trying to create and practice a rational politics of ‘pure reason’ unsullied by the kind of sentimentalism that he and other radicals had poured out in defence of the queen. But this appropriation of rationality, as with much else in political language, was rhetoric crafted for a specific purpose. Carlile’s aversion to sentimentalism in the 1820s was part of the war he was waging with rival radical leaders whose reliance on the effusive, but all-too transient mass platform (large open-air meetings), and the adulation of the credulous masses for romantic radical leaders like Henry Hunt, was juxtaposed to his own rival ascetic, austere rational republicanism. To put it another way, the politics of feeling was central to the rivalry among British radical leaders.

In any case, Carlile’s path to ‘pure reason’ was paved with affective tensions as he struggled to practice what he preached, while it turned out that the destination of ‘pure reason’ he was aiming for was a state of happiness. But this aside, his sentimental response to the queen was neither opportunistic, diversionary or without lasting consequence, as claimed by his biographers who have struggled to explain Carlile’s impassioned response to Caroline.[viii]

The callous treatment of the queen was symptomatic of arbitrary government and the ways in which ‘honest industry is robbed to gratify the bad passions of the idle and vicious’, as Carlile put it. This was the real reason why ‘every vein in’ his body ‘had swelled with indignation at…the filthy tales manufactured’ by the queen’s enemies who were without shame.[ix] All this was grist to the mill of Carlile’s republicanism.

Above all, the queen’s case was an important watershed moment in Carlile’s emerging feminism. By the end of the 1820s, Carlile had become infamous for his controversial views on sex, love and marriage. One of the main rights that he advocated was divorce and free love, by which he meant men and women should marry for love, and be free to divorce if that love ceased. It was no coincidence that Carlile dwelt on the absence of this in the royal marriage: ‘It is much to be lamented that a mutual separation is not legal’, he had written at the beginning of the affair.[x] Women had just as much right to be loved as men.

Carlile claimed that women had the same affective capacity for love as men. Thus, sex should be a mutually pleasurable experience for both parties; his advocacy of birth control was designed to remove the dreaded fear of unwanted pregnancy. Carlile’s feminism was grounded in a universalist notion that all humans had the same potential capacity for feeling, a view which also underpinned his opposition to slavery, as it did for his mentor Thomas Paine.[xi]

Carlile was not the only one for whom the queen’s case was a watershed. More broadly, we can see Queen Caroline affair as a key moment when the notion that the public sphere ought to be an arena characterised by restraint and decency was consolidated. Though humour, sarcasm, irony and theatricality did not disappear from the public political sphere it was never again as obscene and unrestrained as it had been 1820.[xii] Some of this undoubtedly stemmed from a reaction to the emotional over-heating of the queen’s case, a factor in the decision of the Tory government’s decision to drop the Bill of Pains and Penalties in November 1820.

Caroline’s moment of triumph was all-too-brief: she soon lost favour by taking a pension from the government, and when she tried to gain entry to the king’s coronation in July 1821, she found the doors of Westminster Abbey barred. Less than a month later she was dead (from an obstruction of the bowel), a poignant and melodramatic end which led to an outpouring of public grief, and further riots as the authorities tried to quietly ship her body back to her native Brunswick.

Thereafter, as regency radicalism lost much of its sentimentalism, Carlile was at the radical forefront in creating a set of feeling rules that accented restraint, respectability and soberness. But Carlile’s case is a reminder that historians need to be on their guard when historical actors juxtapose their self-proclaimed rationality against emotion. Affairs of the mind or heart are rarely so stark.

[i] Quoted in Nicholas Rogers, Crowds, Culture, and Politics in Georgian Britain. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998, p. 248.

[ii] Thomas W. Laqueur (1982), ‘The Queen Caroline Affair: Politics as Art in the Reign of George IV’, Journal of Modern History, 54, pp. 417-66; Anna Clark (1990), ‘Queen Caroline and the Sexual Politics of Popular Culture in London, 1820’, Representations, 31, pp. 47-68.

[iii] Black Dwarf (1820), 2 August.

[iv] As Rob Boddice notes, the original definition of the word sympathy meant to suffer with. Boddice, Rob (2016), The Science of Sympathy: Morality, Evolution, and Victorian Civilisation. Urbana, University of Illinois Press, p. 3.

[v] Louise Carter (2008), ‘British Masculinities on Trial in the Queen Caroline Affair of 1820’, Gender & History, 20, p. 261.

[vi] Republican (1820), 8 December.

[vii] A Warning Voice to the People of England (n.d. [1820]. London: Jane Carlile.

[viii] Iain McCalman (1993), Radical Underworld: Prophets, Revolutionaries, and Pornographers in London, 1795-1840. Oxford, Oxford University Press, p. 162; Joel Wiener (1983), Radicalism and Freethought in Nineteenth-Century Britain: The Life of Richard Carlile. Westport, CT, Greenwood Press, p. 57; James Epstein (1993), Radical Expression: Political Language, Ritual, and Symbol in England, 1790–1850. Oxford, Oxford University Press, pp. 131-32.

[ix] Republican (1820), 8 December.

[x] Republican (1820), 25 February.

[xi] Nicole Eustace (2008), Passion is the Gale: Emotion, Power, and the Coming of the American Revolution. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, p. 440.

[xii] Vic Gatrell (2006), City of Laughter: Sex and Satire in Eighteenth-Century London. London, Atlantic Books, chs 17-18.