Suzy Lawrence is a PhD candidate at King’s College London. Her research explores moments of individual emotional agency in early modern drama

Suzy Lawrence is a PhD candidate at King’s College London. Her research explores moments of individual emotional agency in early modern drama

In this post, she looks at how connections between fear and time are used to control people’s behaviour in Shakespeare’s Henry V and Boris Johnson’s first lockdown address.

On 23 March 2020, I sat on a sofa, surrounded by the detritus of enforced home schooling, and watched open mouthed as Boris Johnson ordered us all to stay at home. It felt momentous. It also caused me to feel a whole host of different emotions: confusion, anxiety, sadness. But perhaps predominantly, I was aware of feeling fear. Fear of home school, fear of illness, fear for those I loved. I am lucky enough generally not to experience much fear in my daily life which perhaps made this moment feel even more extreme. Luckily for me, however, this was an emotion I had recently been thinking about in great detail. In my research, I look at moments of deliberate emotional change in early modern drama. As I watched Boris give his address, and as I felt the fear rising within me, I also saw a connection form between this moment and the way that fear is treated in Shakespeare’s Henry V. I’m sure Boris himself would have been delighted by the connection.

So, what then was it about that speech that took me back over 400 years? Well, the answer lies in the connection between fear and time and the way this connection can be manipulated by those in power to induce emotion in others. Authors of early modern health guides, which always deal with regulating the emotions, openly acknowledge that fear is an emotion based in the future. Thomas Rogers (1576) therefore describes fear as being ‘an opinion of some Evyll coming towards us’, while Jean D’Espine (1592) describes fear as being ‘caused and ingendered by reason of some imminent danger’.[1] The clergyman Nicholas Coeffeteau (1621) perhaps makes the clearest connections between fear and time, however, when he observes that ‘to cause Feare, the evill that doth threaten us must not bee present but to come; for that when it is present, it is no more a Feare but a mere heavinesse’.[2] These writers are acknowledging the fact that fear is an emotion inspired by the thought of a future unwelcome event. In fact, its existence appears to be entirely dependent on the futurity of that event. When the event arrives in the present, the emotion isn’t even seen as fear anymore, changing instead to become a ‘mere heavinesse’, a word which the Oxford English Dictionary defines variously as displeasure, sadness and grief.

Front cover of A Table of Humane Passions by Nicholas Coeffeteau (London, 1621). Source: LUNA: Folger Digital Image Collection

As well as insisting that fear is an emotion always inspired by an event in the future, however, these writers are also clear that the event must be hard to avoid. D’Espine describes how the imminent danger causing the fear must be one ‘from which we knowe not how to be delivered, whensover it happeneth’.[3] Coeffeteau states that fear is ‘a griefe and distresse of the soule, troubled by the imagination of some approaching Evill, wherewith man is threatened, without any appearance to be able to avoid it easily’.[4] For me, this aspect of fear is crucial because it creates a link between the individual’s sense of personal agency, their ability to shape their future, and their sense of emotional agency, their ability to control their emotions. An event induces fear when an individual believes that they may not be able to avoid it and so it fills their future, seemingly offering no chance for escape. Because of this, it stands to reason that those in power, with the freedom to control how they use their time, may feel more able to dispel their fear than other socially or economically disenfranchised individuals.

Turning from these early modern authors to Shakespeare, it is clear that he is also conscious of these connections between fear, time and agency. In Henry V, Henry makes a speech at the battle of Agincourt to inspire his exhausted and frightened men to an unlikely victory against the dominant French army. The dramatic intention behind this speech is for Henry to change his soldiers’ emotions and thereby shape their actions: he needs to inspire them to fight. He therefore begins his speech by declaring that if any man ‘hath no stomach to this fight | Let him depart’ (4.3.35-36).[5] This is a clever move. In making this statement, Henry is seemingly giving his men some agency and so changing the battle from a moment of fearful inevitability to a moment when men can shape their own future. By giving them some control of their future, he immediately helps to dispel their fear.

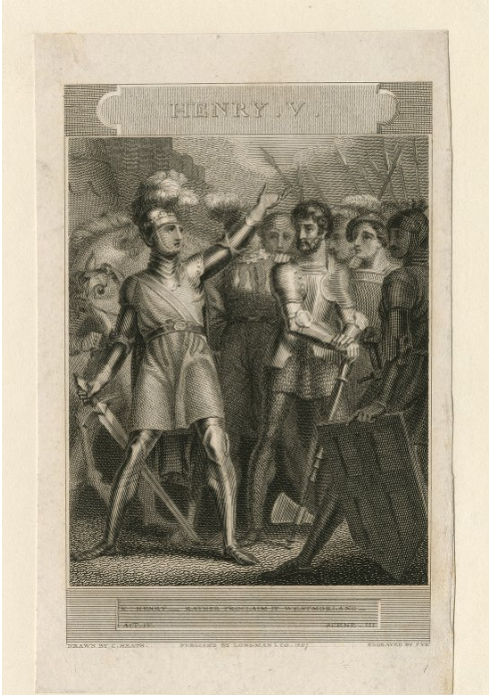

Henry V inspiring the troops at the Battle of Agincourt (Source: Charles Pye, 1807, LUNA: Folger Digital Image Collection)

For those soldiers that stay, Shakespeare also uses the connections between time and fear in the rest of Henry’s speech to make sure that the future is nothing to be scared of. In one key moment, Henry tells his soldiers that:

He that shall see this day and live old age

Will yearly on the vigil feast his neighbours

And say ‘tomorrow is Saint Crispian’

Then will he strip his sleeve and show his scars

And say these wounds I had on Crispin’s day

(4.3.44-48)

This is another clever temporal trick. Henry has little chance of reframing the battle itself as something not to be feared. He therefore directs his soldiers imaginatively beyond the immediate, fear-inspiring danger, to a more welcoming future instead. Indeed, the nature of the place he sends them to is important. While Henry himself prays to God before battle, he doesn’t talk to his men about the opportunity to reach heaven, a place which is hard to imagine. Instead, he fills his soldiers’ minds with visions of an easily imagined and very familiar future, full of neighbourly feasts and the opportunity for happy boasting. The soldiers can focus on this reassuringly familiar but enticingly golden vision, instead of on the unavoidable battle. Henry therefore effectively time-hops them to a better place, putting the battle into their past and placing glory into their future instead. As such, their fear, an emotion which depends on an unwelcome future, is effectively dispelled.

Shakespeare writes Henry V using the connections between time and fear to convincingly portray Henry as dispelling his soldiers’ fears. In the world of the play, this has a clear personal benefit for Henry: his soldiers enter battle and win him reputational immortality. What, though, does this have to do with Boris Johnson and his speech of 23 March 2020? Well, as I listened to it, I started to realise that, just as Henry wants his soldiers to fight, so Boris’ speech is entirely focused on persuading its listeners to change their behaviour as well and that one of the ways it attempts to do this is through manipulating fear.

Henry gives his speech prior to an obvious moment of physical battle. Boris’ first task is to convince the potentially sceptical public that a battle is going on and that they should be scared. It is therefore noticeable that he begins his speech by creating that image of the unavoidable and unwanted future. He does this in three main ways. He describes Covid-19 as the ‘invisible killer’ twice in his speech This is an enemy that is unseen and therefore potentially unavoidable. He intensifies the situation by making it clear that the future is coming so quickly that it is almost here already, we are ‘in a moment of real danger’ where some workers are already on ‘the frontline’. And the future that is racing towards us is a dystopian one, where ‘there won’t be enough ventilators, enough intensive care beds, enough doctors and nurses.’ There are clear connections between the nature of these images and the definition of fearful events given by the early modern authors above. Compressing the four hundred years between their advice and my current moment, I also felt afraid as I contemplated the Covid battlefield that seemed to lie ahead.

A doctor in Italy at the end of a 12 hour shift in a Covid ward, the future that Boris evokes. (Source: Alberto Giuliani, CC BY-SA 4.0).

But, just like Henry wants his soldiers to go into battle, so Boris wants his listeners to fight too: he wants them to stay home, despite the huge personal and economic cost that will incur. Having created fear in at least some of his audience, Boris therefore uses the same tactics as Henry to make those people comply. He makes it clear that this fearful future may not be unavoidable after all because there ‘is a clear way through’ that depends on the listeners’ choices: people can choose to stay home. He also ends the speech confirming that if people do stay home then there will be a glorious fear-free future. Just as Henry describes his soldiers sitting in a pub showing off their scars, so Boris creates a vision where the nation has not only fought off Covid-19 but it has reunited: ‘we will come through it stronger than ever’ and ‘will beat it together’. Always shown in front of a Union Jack, Boris references England’s supposedly heroic past in order to move his listeners’ imaginations through to the fearless future and so also attempts to manipulate their emotions to ensure compliance with his unprecedented request.

The government’s slogan urged people to stay at home to change the future. (Source: Andrew Parsons/ No 10 Downing Street)

In that moment on 23 March 2020, my own emotion was too overwhelming to process with any kind of logical analysis. As the pandemic has progressed, however, being aware of how fear was thought about in the past has certainly helped me to rethink how to feel about it in the present. Everyone’s emotions have been different throughout this pandemic but understanding one of the ways in which my own emotion of fear has been evoked has allowed me to control it more effectively. Indeed, I write this shortly after the government has declared the end of isolation rules. While many are happy to embrace the idea of living with Covid, it is clear that for those who are clinically vulnerable, the fear remains. Acknowledging the connections between time and fear, and how those connections allow emotions and behaviour to be manipulated, can at least give people back some agency in managing any fear they may feel moving forward into the future.

References

Thomas Rogers, Anatomie of the Mind (London, 1576)

Jean D’Espine, A very excellent and learned discourse, touching the tranquilitie and contentation of the minde (London, 1592)

Nicholas Coeffeteau, A Table of Humane Passions (London, 1621)

William Shakespeare, Henry V, ed. by T. W. Craik (London: The Arden Shakespeare, 1995)

Prime Minister’s Statement on coronavirus (COVID-19): 23 March 2020.

[1] Thomas Rogers, Anatomie of the Mind (London, 1576), p. 26; Jean D’Espine, A very excellent and learned discourse, touching the tranquilitie and contentation of the minde (London, 1592), p. 143.

[2] Nicholas Coeffeteau, A Table of Humane Passions (London, 1621), p. 430.

[3] Jean D’Espine, A very excellent and learned discourse, touching the tranquilitie and contentation of the minde (London, 1592), p.143.

[4] Nicholas Coeffeteau, A Table of Humane Passions (London, 1621), p. 430-431.

[5] William Shakespeare, Henry V, ed. by T. W. Craik (London: The Arden Shakespeare, 1995), 4.3.35-36. All subsequent references are to this edition.