Olivia Krauze is a PhD candidate in English at the University of Cambridge. Her research explores the concept of ‘violent emotion’ in nineteenth-century medicine and fiction. Her interests more broadly include affect theory, the medical humanities, sexuality and queer studies, the novel form, periodical culture, and Russian literature.

Olivia Krauze is a PhD candidate in English at the University of Cambridge. Her research explores the concept of ‘violent emotion’ in nineteenth-century medicine and fiction. Her interests more broadly include affect theory, the medical humanities, sexuality and queer studies, the novel form, periodical culture, and Russian literature.

In this guest post for The History of Emotions Blog, she examines how the changing meanings of ‘aura’ in the nineteenth century informed the novels of Thomas Hardy.

A quick search for the term ‘aura’ is likely to lead down two rather divergent paths: spiritual websites and book-length guides on How to See, Feel and Heal the Aura on the one hand, and medical information on the migraine aura (typical in one in three sufferers) on the other.[1] Both of these conceptualisations of the term are relatively modern; in fact, both developed around the same moment in the nineteenth century.

The Greek sense of ‘αὔρα’ as a breeze or zephyr, with its typically poetic associations, persisted in Britain for over one thousand years.[2] Its medical usage, meanwhile, dates back to the second century AD and Galen’s Omnia Opera, in which he described a case of epilepsy in a thirteen-year-old boy, preceded by the sensation of ‘a cold breeze’ originating in the leg and climbing upwards towards the head.[3] However, as Esther Lardreau has pointed out, the nineteenth century ushered in ‘[t]he reconstruction of the concept of the aura epileptica’.[4] In an 1858 review of a recent work on epilepsy, psychiatrist John Charles Bucknill commented on the growing signification of the term:

Some have applied its meaning solely to the sensation of a cold breeze or wind traversing from the periphery to the centre of the nervous system, while others have called any peripheral phenomenon which preceded the fit, by the name aura.[5]

The peripheral phenomena Bucknill went on to describe largely involved pain, discomfort or tremors, but by 1890, Byrom Bramwell, future president of the Royal College of Physicians, wrote that ‘[t]he aura may consist of any sensation which we are capable of experiencing’, indeed, that ‘[i]n many cases, the aura consists of a peculiar feeling, which patients often find it difficult to describe exactly’, ranging from sensory to motor reactions, and even sometimes inducing ‘dreamy states’.[6] If epilepsy was the condition most prolifically studied in this period, the influence of the ever-broader concept of the aura soon spread to studies of other neurological conditions, such as hysteria and migraine.

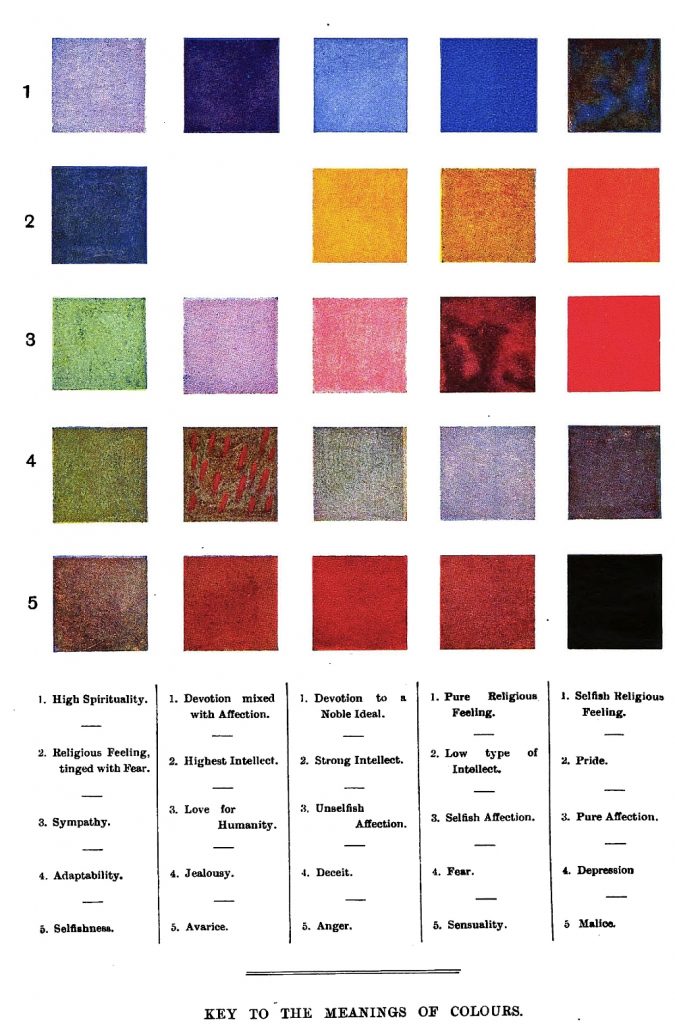

Figure 2: ‘Key to the Meanings of Colours, from Man Visible and Invisible (Plate I). Wikimedia Commons.

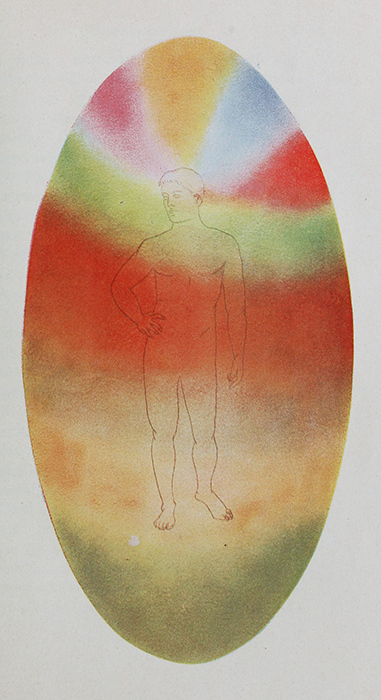

Undoubtedly, a mutual pressure was exercised on the definition of the aura in all its variability and ambiguity by this new medical context and the then co-emergent modern Spiritualist movement. The first issue of The Spiritualist magazine published in 1869 included a report on the lecture of Mr John Jones, ‘a retired city merchant, and well-known friend of Spiritualism’, who attempted to prove that ‘[a] mesmeric aura, seen by sensitives, proceeds from every human being, and influences the actions of people more than most of them are aware’.[7] With the foundation of the Theosophical Society in 1875, members began to conduct individual studies into the aura, which became a key concept for occult theorists. In 1895, Charles Webster Leadbeater published the pamphlet The Aura: An Enquiry into the Nature and Functions of the Luminous Mist Seen about Human and Other Bodies. In his longer 1903 study, Man Visible and Invisible, he even made several attempts to illustrate the aura in its various aspects, as seen from the perspective of the clairvoyant (figs. 2 and 3).[8] As the movement grew, so did assertions that the aura ‘does not appeal solely to mystics and those transcendentally inclined, it has a very practical bearing upon the ills of life; for it prepares the way to a medical system based upon the true nature of the individual’.[9] Comparable claims on the health benefits of self-attunement to the aura pervaded contemporary self-help literature on the subject.

Figure 3: ‘The Astral Body of the Ordinary Man’, from Man Visible and Invisible (Plate X). Wikimedia Commons.

Thomas Hardy, a writer especially attuned to the relationship between body and mind in his works, and a voracious reader of contemporary medical literature, played on all these connotations of the aura in his 1891 novel Tess of the d’Urbervilles. In an important narrative moment, he described Tess’s effect on her lover and husband-to-be, Angel:

Clare had studied the curves of those lips so many times that he could reproduce them mentally with ease: and now, as they again confronted him, clothed with colour and life, they sent an aura over his flesh, a breeze through his nerves, which well nigh produced a qualm; and actually produced, by some mysterious physiological process, a prosaic sneeze.[10]

Hardy’s use of the term ‘aura’ is remarkably loaded here: it combines its Classical meaning, literally ‘a breeze’, with the more figurative meanings the term acquired during the nineteenth century. These meanings meet within the logic of the sentence. The implication is that Tess’s essence or aura, emanating from her lips, in turn produces the medical sense of aura in Angel. Hardy seemed to take to its comic conclusion the potentiality of this latter aura to result in a sneeze, rather than a fit, but retained a latent violence in the threat of the nearly produced ‘qualm’. That the narrator later extols Tess’s ‘healthy thought of a passion as an end’, but hints at something pathological about Angel’s desire for her, acts as a warning of the spasm yet to come.[11] The moment itself thus acts as an aura for the reader, anticipating the tragic fallout from Tess’s confession to Angel, which shatters the fallacy of his own privately conducted studies.

As this whistlestop tour of the changing etymology of ‘aura’ in the nineteenth century has shown, the twenty-first-century associations with which I started this post had a common point of issue, and more of a shared dialectic than might at first appear. Moreover, their co-evolution did not go unnoticed by contemporaries: the aura’s oversubscribed body of meanings provided a rich opportunity for affective expression for literary writers in the late nineteenth century.

References

Byrom Bramwell, Studies in Clinical Medicine (Edinburgh: Y.J. Pentland, 1890).

C. W. Leadbeater, Man Visible and Invisible: Examples of Different Types of Men as Seen by Means of Trained Clairvoyance (New York: John Lane, 1903).

Esther Lardreau, ‘The Difference Between Epileptic Auras and Migrainous Auras in the 19th Century’, Cephalalgia, 27.12 (2007), 1378-1385.

John Charles-Bucknill, ‘Dr Sieveking on Epilepsy and Epileptiform Seizures’, Journal of Mental Science, 4 (London: Longman, Green, Longman & Roberts, 1858), 408-426.

Karl Gottlob Kühn, ed., Claudii Galeni Opera Omnia, vol. 8 (Leipzig: Carolus Cnoblochii, 1824).

Marie A. Walsh, Preface to A. Marques, The Human Aura: A Study (San Francisco: Office of Mercury, 1896), v-vi.

Marion McGeough, A Beginner’s Guide to the Aura: Learn How to See, Feel and Heal the Aura (CreateSpace Independent Publishing, 2018).

‘Migraine with aura’, The Migraine Trust (2021) https://migrainetrust.org/understand-migraine/types-of-migraine/migraine-with-aura/.

The Spiritualist, 19 November 1869.

Thomas Hardy, Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891).

[1] Marion McGeough, A Beginner’s Guide to the Aura: Learn How to See, Feel and Heal the Aura (CreateSpace Independent Publishing, 2018); ‘Migraine with aura’, The Migraine Trust (2021) <https://migrainetrust.org/understand-migraine/types-of-migraine/migraine-with-aura/> [accessed 14/02/2023].

[2] A famous early example sees Odysseus worrying that the cold early morning breeze from the river may overcome him in his feebleness at the end of Book 5. Hom., αὔρη δ’ ἐκ ποταμοῦ ψυχρὴ πνέει, Od., 5.469.

[3] Karl Gottlob Kühn, ed., Claudii Galeni Opera Omnia, vol. 8 (Leipzig: Carolus Cnoblochii, 1824), p. 194.

[4] Esther Lardreau, ‘The Difference Between Epileptic Auras and Migrainous Auras in the 19th Century’, Cephalalgia, 27.12 (2007), 1378-1385 (p. 1383).

[5] John Charles-Bucknill, ‘Dr Sieveking on Epilepsy and Epileptiform Seizures’, Journal of Mental Science, 4 (London: Longman, Green, Longman & Roberts, 1858), 408-426 (p. 410).

[6] Byrom Bramwell, Studies in Clinical Medicine (Edinburgh: Y.J. Pentland, 1890), p. 229.

[7] ‘Reports of Meetings: St. John’s Association of Spiritualists, The Spiritualist, 19 November 1869, p. 2.

[8] C. W. Leadbeater, Man Visible and Invisible: Examples of Different Types of Men as Seen by Means of Trained Clairvoyance (New York: John Lane, 1903).

[9] Marie A. Walsh, Preface to A. Marques, The Human Aura: A Study (San Francisco: Office of Mercury, 1896), v-vi (p. v).

[10] Thomas Hardy, Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891), Chapter XXIV.

[11] Ibid., Chapter XXVIII.