Niamh Cullen is working on a three-year post-doctoral project, at Università degli studi di Milano and University College Dublin, entitled ‘The post-war generation: Growing up and coming of age in 1950s Italy’. The project uses diaries, memoirs, magazines, and popular culture to investigate the changing nature of everyday life, including attempting to reconstruct the experience of everyday emotions. Here she writes about the complex meanings of love and marriage during the economic ‘miracle’ of post-war Italy.

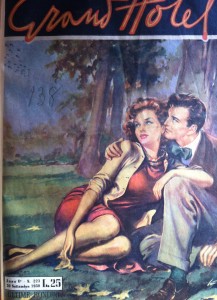

The following advice was given to a reader of the popular Italian magazine Grand Hotel who wrote in 1955 with the pseudonym ‘Gone with the wind’, and it manages to capture in a few words, the complex meanings and expectations associated with love and marriage in 1950s Italy.

It wouldn’t have been very nice of you to marry (the first man) just to have a comfortable life. As for the other one, if he really loved you and had serious intentions, he would be able to persuade his parents to break his obligation. Be careful then dear, (…) neither a marriage of convenience nor a clandestine relationship with a man who is engaged to another. You’ll be left with empty hands and a bitter smile.

Don’t marry just for material comfort, marry for love. And with regard to the second suitor, surely a marriage arranged by his family was no real obstacle if he really loved her? What seems like fairly straightforward, common sense advice at first actually describes two different views of marriage and two different ‘emotional styles’; one that sees economic security, kinship and community bonds as central to marriage, and the agony aunt’s ‘modern’ ideal of true love as the basis of a lifelong union. ‘Gone with the wind’ was caught between these two conflicting positions, unsure which criteria to use in making her choices.

While the idea of romantic love was of course an age-old one, the idea that it might realistically be used as a sound criteria for choosing a partner, and indeed as the basis of a marriage, was a relatively recent one in 1955. Italy too was on the cusp of great social change. Up to the mid-1950s, it was still predominantly a rural society dominated by the Catholic Church and by traditional notions of family, kinship and gender roles. However the late 1950s and early 1960s saw society transformed by an economic boom so strong it simply became known as the miracle. Migration to the cities increased rapidly, as people were drawn away from the countryside by the promise of higher wages and modern city life. Women’s roles in society were changing, consumer culture was on the rise and mass culture was beginning to displace the voice of the priest.

All of these changes had massive implications for the ordinary lives of Italians. I’m particularly concerned with the way that these social transformations affected the day-to-day lives of ordinary Italians, and on how not just their material circumstances but their outlook, attitudes and decisions were shaped by wider social currents. While my research initially focused on the lives of those growing up and coming of age in the 1950s, I gradually came to see as I sifted through magazine articles, stories, advice columns, memoirs and diaries that one of the most fundamental ways in which social and cultural change impacted on day to day life was at the level of the emotions; in the shifting meanings and constant renegotiations of the meaning of love, courtship and marriage. Decisions about when, whom to marry, and whether to marry at all, were central to the lives of young Italians and were bound up with their experiences and expectations of family, work, migration, politics, religion and mass culture.

My research now mainly focuses on courtship in the 1950s, looking at both the popular discourses surrounding it – in magazines, and some fiction and film – and attempting to reconstruct as much as possible the variety of lived experiences and recollections about ‘ordinary’ love, through diaries and memoirs. Looking at the various descriptions and discourses about love and marriage in the 1950s, it can seem difficult to locate the actual ‘emotion’ since sometimes, as in the example quoted above, the reasons for marrying could be about everything but love. However it is in the 1950s that more and more the idea of marrying for love was entering people’s minds, even if it still wasn’t entirely clear how to act on it.

Another Grand Hotel reader wrote in the same year asking for similar advice; she was being courted by two men, one a goldsmith with his own shop and the other a poor labourer who often ‘didn’t even have the price of a cinema ticket’. However she and the labourer ‘loved each other very much and couldn’t live without seeing each other.’ Which suitor should she choose, she asked. The gently mocking response was ‘the labourer, naturally… or do you want to choose the goldsmith and die?’ While the answer was laughably obvious to agony aunt Wanda, and to us today, what is interesting is that it was not at all so to the reader in question. In a rural setting where a woman might have little education and no marketable skills or experience, depending entirely on her husband for financial security, marriage was often seen as too important to be decided by love.

However it was usually not as simple as a clear-cut choice between love and material comfort. Particularly in a close-knit rural community, where a couple might know each other growing up, or get engaged at a young age, it could be difficult to separate family expectations, companionship, familiarity and love. It is also of course impossible to know what any individual really meant or understood by love.

Diaries and memoirs do give some insight into what was felt and described as love, as well the cultural frameworks in which it was understood. Also interesting is the prominence of place given to the theme of love and/or marriage within the overall structure of the life-story. Some of the first-person texts I have looked at describe the courtship with their partner in classic romantic language, borrowing similes from nature, moon and stars, while giving no real sense of the relationship. Others describe the gradual growth of affection often giving great detail on the typical formalized progression of a relationship to official engagement and then marriage. Some admitted that the strictly regimented courtship of the middle-class couple – usually with a weekly schedule for the courtship agreed between the girl’s father and her fiancé, and meetings happening under family supervision – allowed little room for intimacy to develop before marriage.

There was no simple progression from marriages of convenience to ‘modern’ unions based on love either; one memoir recounted the decision of two friends who met at university, to marry for companionship but without love. Sometimes mass culture blended with and gave new life to traditional ideas too. Since separate gender spheres were more rigidly adhered to in rural southern Italy, with women generally keeping to the home, traditional ideas of romantic love were based on meaningful, longing glances exchanged between couples who never spoke a word. Magazines like Grand Hotel, whose main attraction was stories about love, fitted these traditional notions into their modern melodramas. When some memoirs described their love in these terms, it is difficult to tell whether they were more influenced by the magazines so popular in the 1950s, or these much older notions.

It’s almost impossible to tell how people really felt – even when reading their own personal accounts of their experiences – or what they really meant when they used the word ‘love’. However looking at social change through the lens of emotions rather than just material changes, can give much greater insight into how wider trends and developments impacted people’s lives, and how they negotiated them at an individual level. Reconstructing as much as possible the different ways that love might be understood in a society, how they arose and changed over time also allows us to understand how a choice that seems laughably obvious to a so-called modern readership, was anything but clear-cut to the person who had to make it.

Pingback: Love in the time of miracles | Growing up in 'ordinary' times: Life in 1950s Italy