This is a guest post by Ross MacFarlane who is Research Engagement Officer in the Wellcome Library, where he is heavily involved in promoting the Library’s collections.

He has researched, lectured and written on such topics as the history of early recorded sound, the collection (and collectors) of Henry Wellcome and notions of urban folklore in Edwardian London. He has also led guided walks around London on the occult past of Bloomsbury and on the intersection of medicine, science and trade in Greenwich and Deptford.

This blog post is an edited version of a talk – From amulets to apps: an emotional biography of Edward Lovett’s folklore collections – given at the Emotional Objects: Touching Emotions in Europe 1600-1900 Conference on 11th October 2013. A version of that talk is available here: http://www.history.ac.uk/podcasts/emotional-objects-touching-emotions-europe-1600-1900/amulets-apps-emotional-biogaphy-edward

Increasingly, Edward Lovett (1852-1933) is being recognised as one of the most interesting collectors of the early 20th century. Through the amulets, charms and talismans he amassed – one of the largest collections of its kind ever assembled in the British Isles – Lovett was recognised by his contemporaries as one of the most active folklorists of his time. But if we think about the nature of these objects – particularly through the accounts Lovett gives of why they were created or purchased in the first place – perhaps we can think of Lovett as not just a collector of folklore but a collector of emotions.

Objects

The objects Lovett collected ranged from cheap, mass-produced items, to items that were adapted from their original purpose (for example, by inscription). They are objects that capture the differing fears and hopes of those who owned. There’s often an intimate relationship between owner and object: many were handled or worn, or generally hidden from public view and kept close to the body. Indeed, the longer the item was worn, seemingly the more powerful the object was.

Some examples, taken from Lovett’s summation of his collecting practice in the capital, Magic in Modern London published in 1925, will help to flesh this summary out.

A pockmarked piece of coral, similar in feel to damaged skin, was said to help lessen the chances of catching smallpox; moles feet were carried as a cure for cramps; horseshoes tied above beds were said to stop children having nightmares and a range of herbal remedies were employed for different curative purposes (orris root, for example was used to aid the teething of Jewish babies).

In one account offered by Lovett, a fearful mother in Bethnal Green was advised – by him – to cut hair from her daughter who was ill with whooping cough. The hair was put between two bits of bread and thrown onto the street, where it was eaten by a dog. When Lovett next visited the family, the child had recovered (although the health of the dog was not recorded…).

However, the best example from Lovett’s collection of this intermingling of medical fears with tactile objects, are a series of beaded necklaces. In 1914, Lovett learnt from the Medical Inspector of Schools, Urban District Council of Acton, of children wearing necklaces consisting of blue glass beads to ward off bronchitis.

Lovett followed up this information by travelling to the East End: there one of his contacts, a shop owner, revealed she herself wore one of these necklaces. Lovett obtained the following information, that the necklaces “must never be taken off, even to wash [the] child. [They are] often worn a whole lifetime, only being removed to renew the string if broken or rotten” and that the wearers had “a profound confidence in them as a cure for bronchitis”.

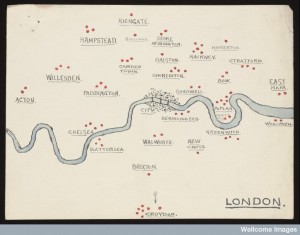

Sketch of London where amulet necklaces were found. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Lovett investigated in 26 districts in London, drawing up a map of his travels, recording the shops where he was offered one of these necklaces for sale when he said he wanted something to cure a child suffering from bronchitis. His search for the necklaces resulting in this visual representation of his travels across London:

Blue Bead Map of London

Aside from the amulets to protect against ill-health, Lovett described and collected materials which could be said to work against other afflictions which would traditionally be seen to be more ‘emotional’ in their conception.

In particular, Lovett comments on the use of plants as love remedies. For instance, “Dragon’s Blood”, which was the nickname for the resin from the Dracaena tree, was sold by East End herbalists as a “love philtre”. The notion being it would be offered by girls to boys who they had a crush on: drink the philtre and the boy instantaneously fell for the girl. Similarly, the root of the Tormentil plant was sold by herbalists to girls: the belief being that the root, burnt at midnight, would induce such strong torments on an ex-boyfriend that he would soon return to his sweetheart.

Similarly, Magic in Modern London, published in 1925, features many accounts of tokens, charms and small mascots carried by soldiers for good luck during World War One. Whilst the accounts given in Magic in Modern London relate to British soldiers, Lovett’s collection included charms from soldiers from the continent. Such accounts and objects offer an entry point into the experience of fighting in the Great War and of the strong emotions and superstitions which were a large part of “trench culture”.

Lovett believed the outbreak of war led to an increase in superstition: a child’s caul was traditionally believed by sailors to protect them against drowning. After the increase in British shipping being attacked by German U-boats, Lovett noticed that such an item increased in price in the docks of East London.

How much emotional investment did Lovett have in his collection? Lovett was very keen to promote himself and from surviving correspondence, there is a strong sense of him using his collection to enhance his status and recognition as an expert on Folklore. As such, he passed on to different museums, a great number of pieces from his collection during his lifetime – often with the caveat that it should be clear that he was the donor to the museum.

This is a slightly different conception to the popular image of the collector-as-hoarder: with Lovett, we have a collector with a more dispassionate, less emotional, relationship to his collection. Indeed, we have an instance of objects imbued with ‘magical’ powers by their owners, becoming acquired by Lovett and being used to increase his social capital.

Fay Bound Alberti has asserted that “Analyzing emotions as experiences and representations situated in the practice of everyday life, helps us to move away from the construction of emotions as abstract entities” [1]. By looking closer at the amulets and charms collected by Lovett from believing Londoners, we can see differing emotions imbued in and even inscribed upon these objects.

[1] Fay Bound Alberti, “Bodies, Hearts, and Minds: Why Emotions Matter to Historians of Science and Medicine,” Isis 100, no. 4 (December 2009): p802.

Enjoyed this blog post? Come to the Centre for the History of the Emotions’s ‘Carnival of Lost Emotions’ on June 4 where you can find out about the objects our researchers invest with emotional meaning and show us your own – we’ll photograph them for our gallery of emotional talismans. Also see more #emotional talismans on Twitter by following @emotionshistory You can find out more about our interest in emotional health at the project website for our new grant ‘Living with Feeling’.