I saw an interesting debate at the ‘general assembly’ of Occupy London this week, which I visited as a blogger / sympathizer / voyeur . The protestors were debating a motion on whether to grant the Tranquility Centre (a group of people charged with maintaining the well-being of the camp) executive powers to eject anyone from the camp who threatened the physical or mental well-being of any other member of the community.

It was a delicate issue. The activists who set up the camp are anarchists. They want to create ‘a society free from authoritarianism’, as a pamphlet put it at the Climate Camp in 2009, which was set up by the same activists. The camp is the message. They’re not just protesting against authoritarian industrial capitalism: they’re living and showing the alternative. In this sense, they’re descendants of Diogenes the Cynic (pictured right) the 4th century BC Greek philosopher who tried to ‘deface the currency’ of capitalism, and who lived in a barrel in the centre of the Athenian marketplace, to display how liberating such a lifestyle was. The philosopher Epictetus said of the Cynic lifestyle: “Look at me, I have no house or city, property or slave: I sleep on the ground, I have no wife or children, no miserable palace, but only earth and sky and one poor cloak. Yet what do I lack? Am I not free of pain and fear?'”

It was a delicate issue. The activists who set up the camp are anarchists. They want to create ‘a society free from authoritarianism’, as a pamphlet put it at the Climate Camp in 2009, which was set up by the same activists. The camp is the message. They’re not just protesting against authoritarian industrial capitalism: they’re living and showing the alternative. In this sense, they’re descendants of Diogenes the Cynic (pictured right) the 4th century BC Greek philosopher who tried to ‘deface the currency’ of capitalism, and who lived in a barrel in the centre of the Athenian marketplace, to display how liberating such a lifestyle was. The philosopher Epictetus said of the Cynic lifestyle: “Look at me, I have no house or city, property or slave: I sleep on the ground, I have no wife or children, no miserable palace, but only earth and sky and one poor cloak. Yet what do I lack? Am I not free of pain and fear?'”

But it’s one thing to run an anarchist commune in the relative seclusion of Blackheath, where the Climate Camp was pegged. It’s quite another to try and run an anarchist commune in the middle of the city, amid all that noise and pollution, with drunks and tourists wandering through. Imagine trying to run a state with no borders, where everyone has a say, and where the citizenship is constantly changing…During the debate, one of the members of the Tranquility Centre spoke out against the motion: ‘Don’t give us these powers’, he said. ‘We don’t want them. It should be the collective responsibility of the community’.

Despite his concerns, the motion passed, through a mass showing of jazz hands. ‘I’m a gay and from an ethnic minority’, said one Indian protestor. ‘We need to feel safe at the camp’. ‘I block the motion!’ shouted one skinhead. ‘You can’t, we’ve been through the process’, said the facilitator. ‘Yes I can! I can do what I want. There’s no police. So I block it.’ ‘It’s already passed’, insisted the facilitator. ‘Let’s move on.’ And so, with one vote, the commune quietly passed from anarchist to…not quite anarchist, and I had a fleeting vision of ten years hence, once the Occupiers have taken control of England, and we have learnt to fear a bang on the door in the middle of the night, and the cry: ‘Open up! It’s the Tranquility Centre!

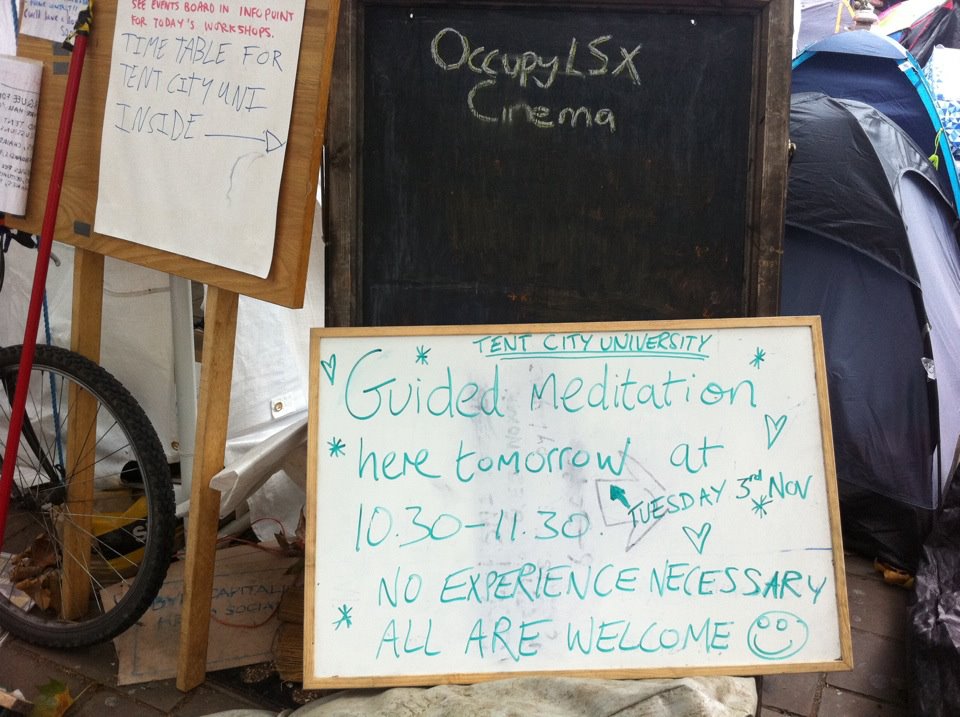

In the camp’s Tent City University, I found myself caught up in a two-hour workshop on ‘acknowledging your emotions’. ‘I want you to pair up, and share your feelings’ we were told. It reminded me rather of the Landmark Forum, a self-help seminar I had attended two weekends before, as research for my book. We were often encouraged to ‘share’ there as well. Adam Curtis of the BBC has covered Landmark (or erhard seminar training, out of which it grew) in his documentary, The Century of the Self. He blamed the human potential movement of the 1970s, which gave rise to Landmark, for killing off the Sixties counter-culture, because it turned outward-looking Sixties protestors into the inward-looking self-help freaks of the 1970s. (Watch his take on the human potential movement in the video-clip here, it’s two minutes 16 seconds in).

Yet, looking at Occupy, I realized the two movements have now come together: both the revolutionary anarchism of 1968, and the human potential movement of the 1970s. The protestors take classes in meditation, in well-being economics, in ’emotion work’ and performance theatre. Occupy is now the revolutionary arm of the politics of well-being. The personal is tied to the political.

Or perhaps Curtis is right. Perhaps the Occupy movement is so Utopian that the political takes second place to more unfocused emoting. ‘My name’s Venus, I’ve started a global movement of love’, one protestor shared with me, before breaking down into tears (she’d been in the camp for two and a half weeks, and I think she was suffering from sleep deprivation).

Revolutions have always been deeply emotional affairs. Plato first used the word ‘privatization’ in The Republic, to describe how, in liberal capitalist democracies, our feelings had all been ‘privatized’ – we never feel collective emotions anymore, except when watching Susan Boyle sing I Dreamed a Dream on Britain’s Got Talent. But after the revolution, he suggested, we would all think and feel as one. Rousseau’s revolutionary politics was also a politics of collective emotion – the citizens would be magically fused together in the ‘General Will’. And they were right, sort of: during revolutions, people get brief and intoxicating flashes of that emotional experience – a whole people, thinking and feeling as one. As Wordsworth put it, reflecting on his trip to revolutionary France in 1790:

Oh! pleasant exercise of hope and joy!

For mighty were the auxiliars which then stood

Upon our side, we who were strong in love!

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,

But to be young was very heaven!

Perhaps the nitty gritty of reforms doesn’t matter so much. Revolutions are in part a reversion from bureaucratic and technocratic politics to a more primitive emotional feeling of communion. But then, of course, you come down from the high, and go home. Or you might actually gain power…and then you have to work out new bureaucracies, new institutions, new technologies of control when the oxytocin has run away, and the distrust and loathing come back. But sometimes perhaps they still remember those moments…the sacrifice, the discomfort, the camaraderie, the elation: ‘you, who were with me in Paris, in Kiev, in Tahrir, do you remember? Do you still feel it?’