This summer the Living with Feeling project launched ‘Developing Emotions’, a new schools engagement programme. Over the next year and beyond, we’ll be working with primary and secondary school teachers to develop educational and pastoral resources about emotions, with the aim of improving children’s emotional literacy and wellbeing. To launch this programme, we held three workshops with teachers, to share our research and explore how we can support those working at the coalface. This blog posts summarises some of the main things we learned from the teachers, headteachers and other educators who attended.

These workshops were a timely intervention, tapping into an increased appetite for discussions about emotional health in UK schools. The Ofsted Inspection Framework 2019 includes a new judgement category of ‘personal development’, which refers to the importance of character and resilience, while emotional wellbeing remains a central topic in relationships and sex education and health education. New statutory guidance mandates teaching the links between physical and mental health; exploring what constitutes a ‘normal’ emotional range; and developing children’s emotional literacy and vocabulary.

While recognising these important changes to the educational landscape, we’re also keenly aware of their possible limitations. Does a focus on building resilience ignore the systemic injustices children and their families might be facing? Do we risk introducing a ‘one-size-fits-all’ template that pathologises certain behaviours or feelings – such as loneliness – as ‘unhealthy’ or ‘abnormal’? We want to reflect that pupil wellbeing and the emotional culture of schools are much more complex than new mandates might suggest. Further to this, we want to avoid being prescriptive about emotions, and champion a child-led approach, that prioritises students’ own experiences, ideas, and feelings. What is a “normal” and “healthy” emotional range for one child in one school will not necessarily feel healthy or normal for another child or in a different school.

In July and August 2019, our workshops – held at the QMUL campus at Mile End – brought together 23 teachers from different schools, including primary and secondary, state and independent. The events attracted heads, teachers in subjects ranging from languages to art to geography, and many with a direct responsibility for pastoral care and wellbeing. We were also joined by a sexual health facilitator from a counselling centre for young people, and a teacher from Turkey who was staying in the UK.

The workshops were shaped by Thomas Dixon’s research into various aspects of the history of emotions and were facilitated by Jenny Pistella, a museum and heritage learning consultant currently completing a PhD at the Centre for the History of the Emotions. The workshops were also supported by Engagement and Impact Manager Alison Moulds, Project Manager Agnes Arnold-Forster, Research Fellow Emma Sutton, and PhD candidates Evelien Lemmens and Dave Saunders. Together, we sought to gauge appetite among the teachers, build partnerships, and measure the impact of these initial scoping events.

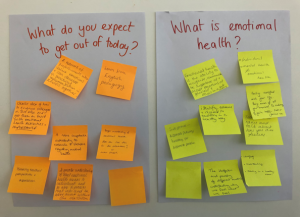

Each of the workshops ran along the same lines, and comprised research-led presentations, group activities and discussion. We began each day by asking attendees ‘what is emotional health?’. We discussed how it might encompass recognising and managing one’s own emotions and those of others, and how it might be a broader category than mental health (and thus a less scary and less medicalised way for children to talk about their feelings). Balance, self-awareness, and emotional literacy were recurring themes. We considered how emotions are a spectrum, and that one person’s version of emotional health might not be the same as another’s. We also asked attendees what they wanted to get out of the day – they were typically looking for new resources, strategies and approaches to teaching emotional wellbeing.

We then invited attendees to participate in a ‘three corners’ debate. They were presented with provocative statements such as ‘crying in public is a bad thing’ or ‘people are less content or happy than they were in the past’. Attendees had to decide whether they agreed, disagreed or were unsure, and then defend their stance and attempt to persuade others of their perspective. The exercise stimulated debates about gender stereotypes, displaying emotions in public and private spaces, nostalgia, and nature vs nurture.

Thomas then gave a series of presentations derived from his research on anger, tears, and friendship – all themes which resonated with teachers’ experiences in the classroom. Thomas described the etymology of and history behind various terms for anger and anger-like emotions, showing how a richer vocabulary could reveal more nuanced or even different feelings. He also explored how the history of friendship – which was originally seen (in a European context) as the preserve of the male elite – might encourage children to re-evaluate their own preconceptions about making, maintaining, and expressing friendships. The purpose of the historical talks was to push beyond the idea of a universal set of basic human emotions and to present a historically and culturally informed view.

The presentations sparked some in-depth discussions about the challenges teachers faced and where they had opportunities to make a difference. They spoke about how they managed and displayed their own emotions in the classroom. Is it okay for teachers to cry in front of children? Can they model healthy emotional behaviours for their pupils? Participants explored the shifting landscape of childhood friendships, including how they are influenced by age and gender, and how they are enacted both in the classroom and in less supervised spaces like the playground. We also discussed the difficulties of problematizing basic emotions when children and teenagers might be struggling to identify their feelings or lack confidence expressing themselves. At the same time, identifying the complex interplay of emotions that might sit behind common behaviours like bullying, aggression, sadness or withdrawal was seen as a key priority.

In groups, teachers discussed how our key themes – anger, tears, and friendship – manifested among school pupils, and how they could be taught in the classroom, using some of the insights derived from Thomas’s presentations.

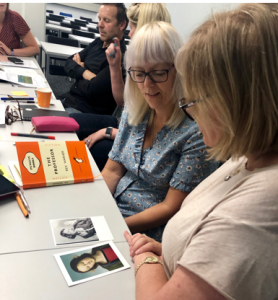

Alison chats to teachers about how different emotions are displayed in the classroom. Photo: Jenny Pistella.

After lunch, we came back together to explore the difficulty of defining emotions, through a series of activities. We used Tiffany Watt Smith’s The Book of Human Emotions, inviting attendees to guess what less familiar emotions words might mean. Teachers felt such word games would translate well to the classroom, with children able to enhance their vocabularies and learn synonyms, etymologies, and root words. Participants were then asked to pick from Jenny’s wonderfully rich collection of artistic postcards to find an image that reflected how they were feeling. In pairs, we then decoded our partner’s mood, based on the image they were displaying.

Two teachers try to decode how the other is feeling by interpreting their choice of postcard. Photo: Jenny Pistella.

After this, we road-tested our new ‘What Are They Feeling?’ game with the workshop participants. Available through our public-facing website, The Emotions Lab, this game asks players to look at historical images of emotional expressions and designate what they think the subject might be feeling. There are no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ answers – although we reveal the original historical designations, the purpose is to show how difficult it can be to ‘read’ emotions, particularly outside of any context. The game also reveals how other players have interpreted the emotions, to convey how varied such responses might be. If you haven’t played already, you can have a go here.

We closed the workshops by discussing ‘next steps’, asking participants to draw up a wishlist of what resources, materials, and support they would like from the Living with Feeling team. There was a huge appetite for further involvement, from us producing tailored lessons plans to delivering whole school assemblies, and even the idea of us running an ‘emotionally healthy school’ accreditation scheme, to recognise best practice. Some teachers reflected on the challenges of ensuring buy-in and engagement across the school, particularly in the face of other pressures such as exams and Ofsted. Some schools offered to test-run or trial our resources, gauging their suitability for use in the classroom setting and with different age groups. We also explored how we might evaluate the success of the Developing Emotions programme, whether that be through measuring children’s emotional intelligence or tracking their behaviour and attendance over the course of their involvement.

At the end of the day, we asked all participants for their feedback on the workshops. We received an overwhelmingly positive response. Many teachers indicated that they felt a historical approach to the subject was particularly powerful because it presented a ‘safe’ and ‘non-threatening’ way for pupils to discuss emotions at one remove from their own feelings. Another teacher added that history ‘helps pupils to identify that they are not alone’. Asked what they would take away, one headteacher remarked, ‘I now feel that with the correct staff training it can be taught successfully throughout the school. It will make a HUGE difference to the children’. A secondary school teacher said the workshop had ‘motivated and inspired’ her, while an assistant head suggested it had provided ‘creative and practical ideas’ for teaching, as well as ‘more confidence in delivering sessions’ that will gain staff ‘buy-in’.

This is just the beginning. We’re now setting up a network of interested teachers (and related professionals), who would like to work with us to take forward the ‘Developing Emotions’ programme. If you’d be interested in finding out more, please get in touch with us Thomas Dixon at: t.m.dixon@qmul.ac.uk or follow us on Twitter @DevelopingEmo.