Rosalind White is an AHRC funded PhD student at Royal Holloway, University of London. Her thesis is an intimate exploration of natural history that examines the lives of its practitioners beyond the impact of conventional watersheds, and you can follow Rosalind on Twitter @rosalindmwhite.

Rosalind White is an AHRC funded PhD student at Royal Holloway, University of London. Her thesis is an intimate exploration of natural history that examines the lives of its practitioners beyond the impact of conventional watersheds, and you can follow Rosalind on Twitter @rosalindmwhite.

Rosalind’s article ‘”What of her glass without her?” Prismatic Desire and Auto-Erotic Anxiety in the Art & Poetry of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’ has recently been published in the Journal of Pre-Raphelite Studies Vol. 28 (Spring, 2019) She also has a forthcoming chapter, ‘Crawling at your feet, you may observe a Bread-and-Butterfly’: Insects in Literature and Language’ in A Cultural History of Insects in the Age of Industry 1820-1920(Bloomsbury Academic, 2019).

In this post for the History of Emotions Blog, Rosalind ponders how the histories of emotions and of material culture can come together, especially for scholars of Victorian culture.

How do we approach an age that, increasingly, feels unanchored from our emotional present? Why do the outsized passions and curious habits of the past, often evade faithful restoration? As we take what has been termed a ‘material turn’[1] in Victorian studies, appraising an object’s function has become secondary to uncovering an object’s emotional afterlife. We are still interested, for example, in a fossil’s paleontological value, but are perhaps more eager to learn that they were routinely licked by enthusiastic geologists tongue-testing for mineralisation. Our concern with the affective capacity of an object has led to an intersection between the study of materiality and the burgeoning field known as the ‘history of emotions.’

Thomas Dixon stresses that by ‘anatomising the feelings of the past – pulling apart the beliefs, physical places and material cultures of which they were composed’ we can use ‘history imaginatively to inhabit the worldviews and mental pictures’ of the people we study.[2] A marked area of common ground is the desire to intimately enquire into that which lies on the periphery of grand narratives. But what does it mean to reconcile the material with the emotional, and why does this augmented approach, in particular, resonate with studies of the Victorian era?

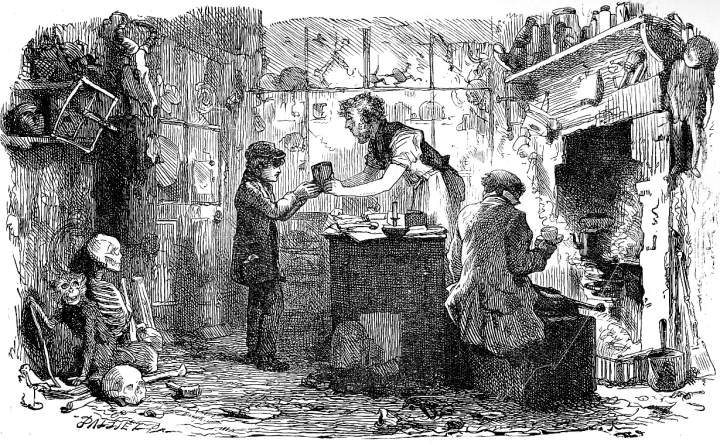

Marcus Stone, ‘Mr Venus Surrounded by the Trophies of His Art’, in Charles Dickens, Our Mutual Friend (London: Peterson, 1865), p. 112.

The Victorian novel, bursting at the spine with newfangled utensils, cursed heirlooms, unsavoury curiosities, and priceless knick-knacks, is infamously crammed with detailed particulars. Infamously dubbed a ‘baggy monster’,[3] the genre showcases how materially-minded Victorians lived by a process of affective accretion: whereby an object might amass an array of attachments in its ‘lifetime’. The emotional infrastructure of the novel, comprised of stray limbs, stuffed canaries, and dust mounds[4] in buoyant circulation, is mirrored in numerous nineteenth-century ventures. The library, for example, thrived on the principal that ‘books, like coins, are only performing their right function when they are in circulation’.[5] Equally, pursuits such as natural history prospered under an attitude that encouraged the passing on of infinitesimal observations. An eye for fossils, today an expert affair, was in the nineteenth century mastered with mimetic fervour. The printing press provides us with perhaps the most obvious example of affective accretion. Advances such as steam-powered printing machines, cheap woodcuts, the penny post and the railway brought about a staggered revolution, whereby an increased consciousness of simultaneity pulsated across the populace. Writing by steam in the nineteenth century, like the digital revolution of today, foreshortened physical borders, allowing concepts, emotions, and products to inexplicably ‘go viral’.

Today, in an effort to manifest the material world, scholars have, somewhat ironically, turned to the technical wizardry of various digital sources. Digital facsimile software available at many libraries[6] and on sites like Google Books or Archive.org provide readers with the chance to flick through rare first editions, or even sepia-stained original manuscripts. This has also allowed scholars to dredge up all manner of hidden curiosities that recur in a text, whether through a simple search, or through more specialised concordance-based digital humanities projects, such as the CLiC Dickens project.[7] Victorianists, like the Victorians themselves, seem determined to make sure that the ephemeral endures.

Recent advances in digital humanities have coincided with an increased interest in retaining a sense of past readership. Academics and librarians who in the past may have removed a dried fern creeping up a margin would today always keep some record of the specimen for posterity (whether through a photo or the inclusion of a protective barrier.)[8] More attention is now afforded to extra-textual information than ever before. University courses or book clubs now frequently choose to read a Victorian novel in serialised format, in an attempt to reconstruct the psychology of a work’s original audience. Special attention is paid to the visual vernacular of the common people, and how it may have shifted: for example, as chromolithography took off, the book became an aesthetic object. Likewise, marginalia provides us with, perhaps, the most obvious extra-textual additions.

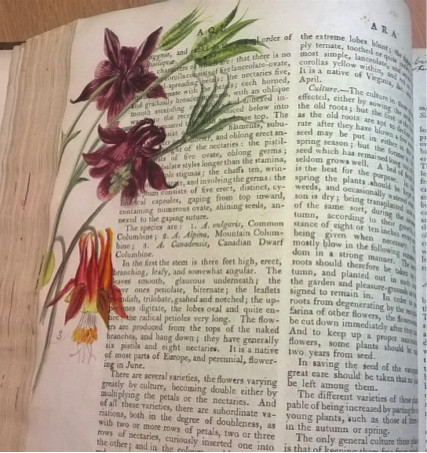

Paintings by Elizabeth Hood in the margins of the un-illustrated edition of Bentham’s Handbook of the British Flora, (1858)

The practice of leaving ample space for a reader’s additions is part of a long held convention in my own field of natural history. Naturalists, when greeted with an uninspired wall of text, frequently lavished their books with hand painted illustrations. I have come across a number of triumphant annotations alongside a rare specimen; ‘(!!!)’ for example, follows the label ‘Bryum roseum in fruit’ in William Henry Fox Talbot’s botanical specimen album.[9] Similarly, comments such as ‘partout’ (everywhere) or ‘where is it not’ pepper the journal of the young naturalist Emily Shore: indicating, perhaps, her frustration that her illness prevented her from collecting more exciting specimens that lay further afield.[10].

The methods, sub-fields, and software that reconcile studies of materiality with research into the history of emotions, increasingly, allows us to access the unguarded minds of the people whose lives and ideas we study. This short post is written in the hope of prompting further scholarship that will question the rubric of this, emerging, inter-disciplinary field.

[1] Pykett, Lyn, ‘The Material Turn in Victorian Studies’, Literature Compass, 1.1 (2004), <https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-4113.2004.00020.x>

[2] Dixon, Thomas quoted in ‘The Emotional Turn in the History of Medicine and the View from Queen Mary University of London’ by Colin Jones, Social History of Medicine, Virtual Issue Emotions, Health, and Well-being, (2012), p. 1.

[3] Coined by Henry James in the preface to the New York edition of The Tragic Muse (1908) (1:x).

[4] See Silas Wegg and his marauding leg, Mr Venus’ den of taxidermy, and the Harmon dust mounds in Charles Dicken’s Our Mutual Friend (1865).

[5] Thomas Greenwood, Public Libraries: A History of the Movement and a Manual for the Organization and Management of Rate-Supported Libraries (London: Simpkin Marshall, 1890), p. 5.

[6] The British Library’s ‘Turning the Pages’, for instance, offers readers the ability to leaf through and magnify various pages of rare items (like Lewis Carroll’s original manuscript of ‘Alice’s Adventures Underground’.)

[7] The CLiC Dickens project demonstrates how computer-assisted methods can be used to study nineteenth-century texts. The project started at the University of Nottingham in 2013, it is now a collaborative project with the University of Birmingham.

[8] See, for example, Geoffrey Belknap’s ‘A Thing of Beauty’ for the ‘Constructing Scientific Communities’ blog <https://conscicom.org/2015/01/02/a-thing-of-beauty//>

[9] See the botanical specimen album of William Henry Fox Talbot at The British Library MS 88942.

[10] The Journal of Emily Shore, [1831-1839] ed. by Barbara Gates, (University Press Of Virginia, 1991).