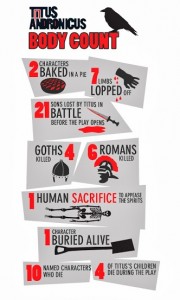

One of the posters for the current RSC production of Titus Andronicus is an info-graphic of the play’s body-count.

Shakespeare’s first tragedy, revived by Michael Fentiman for the RSC this summer, is a story of blood, tears, rape, and entrails. From the opening scenes, in which Titus orders the ritual disembowelling of the Goth Queen Tamora’s son, the violence and revenge spiral out of control, culminating in Act 5 in a macabre cannibalistic feast in which Tamora (now Empress of Rome) unwittingly eats her own sons, the rapists of Titus’s daughter Lavinia, who has assisted in their butchery, collecting their blood in a kind of inverted eucharist. Throughout the play, hands, tongues, heads, and bowels are lopped, trimmed, and hewn. Lavinia is not only raped, but has her tongue and hands cut off by her assailants, Demetrius and Chiron.

The Most Lamentable Roman Tragedy of Titus Andronicus was first performed in the early 1590s. It was initially successful, but during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was thought to be so coarse, disgusting and violent that it could not have been by Shakespeare, and fell out of the repertoire. In the 1850s a bowdlerized version of the play was staged in England, rewritten to give greater prominence to the character of Aaron the Moor, as a vehicle for the celebrated black actor Ira Aldridge. A review at the time wrote: ‘Those who have read the play will remember that it contains many scenes not well suited for public representation. This objection has been overcome by judicious arrangement – nearly all the objectionable passages being expunged, and the poetical and beautiful ones, with which this play abounds, were retained in their integrity’.

The central event of the original play – the rape of Lavinia – was literally unstageable in the Victorian era, as Jonathan Bate has observed. It would be another hundred years before the unexpurgated original was successfully revived, by Peter Brook at Stratford, with Vivien Leigh playing Lavinia to Laurence Olivier’s Titus in 1955.

I became fascinated by Titus Andronicus in the course of researching the history of tears and weeping, and so I was excited when I learned that the play was being performed in this new production directed by Michael Fentiman at the RSC during 2013, featuring Stephen Boxer as Titus and Rose Reynolds, making her RSC debut, as Lavinia. The final scene in Fentiman’s production left me shaken and stunned. It is hard to describe its impact, but it is an extraordinary fusion of farce and tragedy – Stephen Boxer, playing Titus, cross-dressing as a jaunty French maid, oversees a bloodbath of a dinner party worthy of The Godfather or Reservoir Dogs – the audience is thrown into simultaneous convulsions of laughter and horror.

Rose Reynolds as Lavinia in the 2013 RSC production of Titus Andronicus, directed by Michael Fentiman. Photograph by Simon Annand.

The relationship between Titus, deranged by grief, and his mutilated daughter is at the heart of the play, and the role of Lavinia is unusual and demanding – involving a great deal of acting but relatively few lines (since the character’s tongue is cut out at the end of Act 2). The discovery of Lavinia by her uncle, her subsequent encounter with her father, and her death at his hands at the climax of the play, were all moments that moved me to tears when I saw the performance and so I was particularly interested to know what Rose Reynolds thought about the demands of the role and the place of emotions in Shakespearean tragedy.

Rose very kindly agreed to share some of her thoughts on these topics in a Q&A for the History of Emotions Blog, discussing horror films, violence against women, breathing exercises, and the nature of hysteria…

Do you think the extremes of violence and black comedy in Titus Andronicus appeal to a modern audience raised on Tarantino and Scorcese?

Tarantino and Scorcese are masters of macabre. Django Unchained, The Departed, now cult classics, have glamorised violence and have made thrilling cinema by it but audiences’ fascination with blood-shed isn’t a new thing. Directors John Landis, Sam Raimi, George Romero and John Carpenter, godfathers of the horror genre, started a trend back in the seventies, eighties. Young people’s appetite and appreciation for horror over the past twenty years has grown considerably and to have a play like Titus Andronicus revived at such a time is very exciting.

What kind of research and preparation did you do to explore the darker side of your role, and what did you find most difficult about it?

I tried to work technically to achieve the darker sides to Lavinia. I thought that methodically imagining members of my family’s heads being cut off eight times a week would be exhausting and unsustainable. Of course to a certain extent I have to think such thoughts, for Lavinia these events do happen, but to know where Lavinia ends and I begin I concentrate on using various physical exercises.

Before a performance I spend a good portion of my warm up on my back with my legs in the air. It’s orthodox. I engage my stomach and thigh muscles and try to send my legs very slowly over my head. The tension created by engaging my stomach and leg muscles, as well as flexing my feet, sends a shudder through my body and my breath comes in short waves. It’s an unsettling, claustrophobic feeling, close to that of someone experiencing a panic attack. Because my time between being dragged off and my discovery is short and filled with costume and makeup changes I don’t have time to repeat this exercise before I go on stage. For a lot of the scenes in which I have to show emotion I try and remind myself how my body felt during that exercise. If my body and breath are working in tandem and I’m really listening to what’s being said to me, I trust my acting will follow!

Do you think that the figure of Lavinia has contemporary significance for women in the public eye, in that she is first sexualised and then silenced?

Absolutely. Throughout Titus, Lavinia is objectified by those around her, mainly her male counterparts: Titus, Saturninus, even Bassianus at one point says ‘…I am possessed of that is mine.’ When Lavinia does have a voice often she is not at liberty to use it. This is a recurring theme not just for women in the public eye but for women all over. In our production we very deliberately wanted to create a mash up of worlds, most specifically in our design of the play. You can see Christianity in the stained glass windows and Islam in our nuns’ hijab.

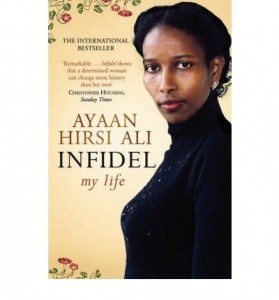

As part of my research for Lavinia I read Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s autobiographical book Infidel, which vividly describes Hirsi Ali’s youth in Somalia and Saudi Arabia, her subjection to female genital mutilation at a very young age and her later involvement in politics and women’s rights. Infidel is an honest, brave, book with Hirsi Ali’s voice loudly speaking out on behalf of Islamic women when at times she felt she couldn’t or shouldn’t. She was a huge inspiration for me in finding a voice for Lavinia.

As part of my research for Lavinia I read Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s autobiographical book Infidel, which vividly describes Hirsi Ali’s youth in Somalia and Saudi Arabia, her subjection to female genital mutilation at a very young age and her later involvement in politics and women’s rights. Infidel is an honest, brave, book with Hirsi Ali’s voice loudly speaking out on behalf of Islamic women when at times she felt she couldn’t or shouldn’t. She was a huge inspiration for me in finding a voice for Lavinia.

When I saw Titus at the Swan, I looked around the audience to see whether other people were crying (or fainting or vomiting). Have you witnessed many extreme reactions to the performance?

We have. Lavinia’s entrance after her rape and mutilation is notorious for causing audience members to experience extreme reactions; this was notable in Lucy Bailey’s production at the Globe in 2006. In our production we have had people have to leave, vomit or faint and I’m told there are sick bags at the end of each row. This may be a rumour!

Traditionally, tragedy was thought to be a genre that inspired emotions of terror and pity. Do you think it should still fulfil those roles?

Yes, but there is also something very interesting in seeing strength and beauty in tragedy. One can feel sorry for Lavinia but she isn’t a victim, nor would I want an audience to perceive her as one. Her active strength in readapting to a new way of life is admirable. I think at first glance anything can seem ugly but when you look again you might see beauty. Every emotion has a counterpart and switching between two emotions on a hair pin or even experiencing two simultaneously is very interesting for an actor to explore. In hysteria there is both joy and great sadness.

You have previously played other tragic characters, including Medea, but are currently appearing in two comedies at the RSC alongside Titus. Which do you prefer?

That’s like being asked to choose which child I prefer! I have thoroughly enjoyed working on all three Swan productions and I’m very lucky to be working on such different material. A Mad World My Masters offers light relief after a Titus – I often feel like a swot rebel bunking off school – whereas Titus offers a cathartic release. You need to cry, sometimes and you also need to laugh until your stomach hurts. All three plays at the Swan this summer are in perfect balance which is why I don’t think I could ever pick. I need both tragedy and comedy in equal measure to be sustained not just as an actor but as an individual.

Rose Reynolds is appearing in Titus Andronicus, A Mad World My Masters, and Candide at the RSC, until the end of October.

You can read more from Rose Reynolds on her RSC blog, more about tears in Titus Andronicus in a previous post on this blog, and more about the current RSC production of TItus Andronicus at The Shakespeare Blog, including clips from a Q&A here and here.

Pingback: Violence, vomit, and hysteria: An interview with Rose Reynolds | c19 Mad Men