I had the pleasure of meeting Jonathan Haidt on Monday at the RSA. Haidt, as you all know, wrote The Happiness Hypothesis, which really inspired me. I gave him a copy of my new book, so if you see it in a bin near the Strand, it’s yours!

Haidt’s own new book is called The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Religion and Politics. It’s a very interesting and quite ideas-packed book. A lot of ‘intelligent non-fiction’, particularly in psychology, can be easily boiled down to a 10-minute TED talk (indeed many books should have stayed as TED talks), but Haidt’s book – shock horror! – has more than one idea in it. It talks about the emotions beneath different political ideologies, how our brains generate sacred values, and how religions help societies to cohere and bond.

Haidt’s own new book is called The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Religion and Politics. It’s a very interesting and quite ideas-packed book. A lot of ‘intelligent non-fiction’, particularly in psychology, can be easily boiled down to a 10-minute TED talk (indeed many books should have stayed as TED talks), but Haidt’s book – shock horror! – has more than one idea in it. It talks about the emotions beneath different political ideologies, how our brains generate sacred values, and how religions help societies to cohere and bond.

It’s this last idea that Haidt discusses in his very slick TED talk on religion and ecstasy (I love the animated slides – it’s lecture-as-movie-experience). His talk begins with William James, and a brief look at revelatory ecstatic experiences – those moments where, as Haidt puts it, a door seems to open in our heads, and we are suddenly lifted from the profane to the sacred. Haidt talks about how such revelatory experiences can involuntarily happen to us (we are seized by forces, as the young Wordsworth feels himself to be), or we can voluntarily engineer them by taking psychedelic drugs, as shamans did (or do).

Then Haidt moves, quite rapidly, to a social or Durkheimian explanation of religion. Sacred values, he says, give societies something to cohere around, to coalesce around. They help us bond, and help our societies endure and resist external shocks. He shows us the fascinating work by the anthropologists Richard Sosis and Eric Bressler, who studied American communes in the 19th century, and found that the religious communes which demanded a lot more from their members survived far longer than the secular communes which demanded less (see the graph below).

So, and this is Haidt’s main point, perhaps there’s an evolutionary purpose to religions. Perhaps they evolved at a certain period in human evolution, around 10,000 years ago, to help human tribes to cohere and cooperate, making them more adaptive and resilient. They are the product, he suggests, of ‘group selection’ – apparently a rather controversial idea in biology.

You can be an atheist, as he is, and still have respect for the sacred and its socially adaptive function. ‘And you don’t need the supernatural for a sense of the sacred’, he insists. ‘You could get it from your country, or from nature.’ Well, maybe, though I’d suggest if people get really worked up about their country, there’s probably a bit of the supernatural mixed in – think of how American nationalism is often mixed in with a sense of manifest destiny.

Haidt is certainly right that religions can bond societies together and help give them a collective sense of meaning, and that this can help them respond to shocks and threats. Others have also argued this recently – from the philosopher Charles Taylor to Robert Wright to Alain De Botton. At a time of riots and revolutions, it’s unsurprising that liberals suddenly start talking about how religions create social stability, as Edmund Burke and William Wilberforce did after the French Revolution.

But I think the Darwinian social function theory of religion leaves something out. It leaves out the phenomena that Haidt begins his TED talk with – the sheer strangeness of revelatory and ecstatic experiences. In such moments, humans feel invaded by external powers, filled with the holy spirit, possessed, overwhelmed. There is something extremely wild, psychotic even, about some religious phenomena, and I think both Haidt and De Botton, in their eagerness to rehabilitate religion for a polite secular bourgeois audience, leave some of that wildness out.

Haidt presents a nice evolutionary story: at a certain stage of evolution, humans came up with religion to help our tribes cohere. But the story is weirder than that. At a certain stage in evolution, humans became conscious, and felt bombarded by messages from gods and angels. We tripped into consciousness, and this must have been both an awesome and a completely terrifying experience. It seems to me that William James appreciated the savage rawness and weirdness of the revelatory experience. Haidt does to some extent, but not sufficiently. (That’s St Theresa on the right, by the way, getting slapped around by some angel. Take that Theresa!)

Haidt presents a nice evolutionary story: at a certain stage of evolution, humans came up with religion to help our tribes cohere. But the story is weirder than that. At a certain stage in evolution, humans became conscious, and felt bombarded by messages from gods and angels. We tripped into consciousness, and this must have been both an awesome and a completely terrifying experience. It seems to me that William James appreciated the savage rawness and weirdness of the revelatory experience. Haidt does to some extent, but not sufficiently. (That’s St Theresa on the right, by the way, getting slapped around by some angel. Take that Theresa!)

I put this to Haidt, and he began by saying that James was a depressive recluse, so was focused very much on the individual aspects of religious experience rather than the social. Fair enough, though a bit harsh on James.

Haidt then suggested that homo sapiens believed the universe was full of spirits as a side-effect of evolving a theory of mind. It was very adaptive to be able to infer other humans’ intentions, and as a result, we started to infer intentions everywhere – the sky thunders because God is angry etc (this is a theory known as the Hyper-Active Agency Detection Device, which Jesse Bering ably explored in his book The God Instinct).

But, again, I don’t think this adequately explains revelatory experience. The experience of hearing voices, seeing visions, feeling suddenly filled with the holy spirit etc is simply far more powerful and immediate than inferring divine agency when you hear some thunder. It’s a feeling of being actively invaded and overpowered by an external agency.

Such experiences can certainly be socially cohesive, but they can also be highly socially disturbing. They are weird, uncanny, abnormal, frightening. The people who experience them are, traditionally, weird, frightening figures, half in the tribe and half out of it (half in the profane world and half in the sacred, as Mircea Eliade put it in his study of shamanism). They might be revered by their tribe and followed. Or they might be executed for being demonically possessed.

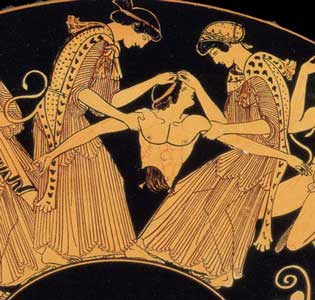

Haidt emphasizes the social cohesion role of the sacred, and seems to suggest our Enlightenment cultures need a bit more of the sacred in our lives and societies. But the sacred is notoriously hard to manage, politically, as King Pentheus knew (he’s the hero of Euripides’ Bacchae, who tries to ban the ecstatic cult of Dionysus and even tries to imprison Dionysus, but the god of ecstasy escapes and sends Pentheus into madness – he ends up getting ripped apart by the maenads).

Haidt emphasizes the social cohesion role of the sacred, and seems to suggest our Enlightenment cultures need a bit more of the sacred in our lives and societies. But the sacred is notoriously hard to manage, politically, as King Pentheus knew (he’s the hero of Euripides’ Bacchae, who tries to ban the ecstatic cult of Dionysus and even tries to imprison Dionysus, but the god of ecstasy escapes and sends Pentheus into madness – he ends up getting ripped apart by the maenads).

What I admire about ancient Athens in the fifth century BC is its ability to balance the rationalist with the irrational and daemonic: Socrates and Sophocles, two sides of the human personality balancing each other out. But our Enlightenment societies have far more difficulty in seeing any value in the ecstatic, the revelatory or the daemonic. It simply terrifies us. It’s too weird, too uncivic, too impolite.

The last generation to be genuinely OK with revelatory experiences was the civil war generation of Oliver Cromwell, the Quakers and John Milton. In some ways, you could read Milton’s Samson Agonistes as the swan-song for revelatory experience in western culture. Samson sits in jail, wondering why God isn’t sending him any more messages. Well – we’re all wondering that now Samson. Why aren’t we getting any messages? What’s up with our reception!

After the prophetic violence of Milton’s generation, England settled down to a calmer and more polite culture that was very suspicious of religious ‘enthusiasm’. And with good reason: the ‘voice of God’ often told people to kill, as God tells Samson to do. Such experiences have to be controlled and even banished in a multicultural rational commercial society. (Check out this excellent video of Stanley Fish discussing the inherent weirdness and illiberal savagery of Samson Agonistes, by the way).

Soren Kierkegaard was right, I think, to insist on the strangeness and irrationality of religious experience in his 1842 book Fear and Trembling. Kierkegaard was surrounded by 19th century Deists and Hegelians trying to turn religion into something nice, polite, rational and civic (as Haidt and De Botton are trying to do today). And he responds, forget all that – religion is God telling Abraham to kill his son, and Abraham agreeing.

Soren Kierkegaard was right, I think, to insist on the strangeness and irrationality of religious experience in his 1842 book Fear and Trembling. Kierkegaard was surrounded by 19th century Deists and Hegelians trying to turn religion into something nice, polite, rational and civic (as Haidt and De Botton are trying to do today). And he responds, forget all that – religion is God telling Abraham to kill his son, and Abraham agreeing.

Religions certainly fulfill an important social role. But they also grow out of the fact that, as a species, we sometimes feel invaded and possessed by external forces. Religions make sense of such experiences and give them a structure and meaning. And perhaps they give us a way to tell the good messages from the bad ones – the pro-social from the anti-social.