Liz Gray is a PhD student at the QMUL Centre for the History of the Emotions. Her doctoral research is into the work of the physician and comparative psychologist, William Lauder Lindsay. She has recently launched her own blog: Tales of Animals Past. In this blog post she tells the remarkable story of ‘Greyfriars Bobby’.

Liz Gray is a PhD student at the QMUL Centre for the History of the Emotions. Her doctoral research is into the work of the physician and comparative psychologist, William Lauder Lindsay. She has recently launched her own blog: Tales of Animals Past. In this blog post she tells the remarkable story of ‘Greyfriars Bobby’.

__________

In an Obituary published in the Scotsman in January 1872, and reprinted in papers across Scotland and as far south as London, one of Edinburgh’s most famous residents is described as ‘a poor but interesting dog’. For the last fourteen years of his life, and for over a hundred years since, Greyfriars Bobby, has been known as one of the most faithful dogs to have ever lived.

The most traditional version of his story is one of a small dog, a Skye Terrier, who, upon the death of his master, mourned him greatly. After the funeral he never returned home, choosing to live instead in the graveyard of Greyfriars church. He was seen sitting at, or near, the graveside every day following the funeral, to the day he died. This demonstration of such dedication to his master engendered him to the hearts of the city’s population. Local restaurateurs fed him, and the observation of his daily routine of sitting in the graveyard, visiting the castle and trotting to visit the local businesses that cared for him, became part of the tourist trail. Upon his death, he was buried in the graveyard that had become his home.

Since his first appearance in Greyfriars (c.1858), Bobby has been the subject of paintings, photographs, films, books, and most famously a statue. Yet, in the most recent biography Greyfriars Bobby: The Most Faithful Dog in the World, Jan Bondeson, posits a most interesting scenario – there were in fact two Bobbys. His examination of the images and descriptions of the dog, alongside the many variations in narrative that make up the legend of this dog, result in a tale of a stray dog, who through chance and luck was ‘adopted’ by members of the community (both Edinburgh’s and the animal advocates for Britain). And when he died (Bondeson suggests in 1867) he was replaced by another, similar, dog. But why? And what does this publicity stunt say about the emotionality of man towards animals.

Since his first appearance in Greyfriars (c.1858), Bobby has been the subject of paintings, photographs, films, books, and most famously a statue. Yet, in the most recent biography Greyfriars Bobby: The Most Faithful Dog in the World, Jan Bondeson, posits a most interesting scenario – there were in fact two Bobbys. His examination of the images and descriptions of the dog, alongside the many variations in narrative that make up the legend of this dog, result in a tale of a stray dog, who through chance and luck was ‘adopted’ by members of the community (both Edinburgh’s and the animal advocates for Britain). And when he died (Bondeson suggests in 1867) he was replaced by another, similar, dog. But why? And what does this publicity stunt say about the emotionality of man towards animals.

Dogs featured heavily in nineteenth-century society: their lives were depicted in literature, in moral tales for children and adults, such as Ouida’s Puck; they were subjects of scientific research, especially in the form of vivisectional experiments; and, related to this, were the focus of philanthropic and charitable works. Greyfriar Bobby’s statue is not the only dog statue in Edinburgh –Bum, the San Diego dog is immortalised in Prince’s Gardens, but he was a stray adopted by a city, there is no tale of faithfulness attached to him. Nor was he the only ‘Cemetery Dog’ of the nineteenth century – Bondeson identifies forty-six such animals, and many of these have their own ‘folk tales’, and statues that attract visitors to these memorials. Yet it is argued that Bobby is probably the most famous of all. He was, and always has been a tourist attraction. Maybe one of the first animals used in advertising, the first of a long line of dogs used in this manner – the Dulux dog and the Andrex puppy being just two that are most recognisable today. These dogs are used to embody qualities such as loyalty and reliability, traits that can be traced back to the little dog from Edinburgh.

Dogs featured heavily in nineteenth-century society: their lives were depicted in literature, in moral tales for children and adults, such as Ouida’s Puck; they were subjects of scientific research, especially in the form of vivisectional experiments; and, related to this, were the focus of philanthropic and charitable works. Greyfriar Bobby’s statue is not the only dog statue in Edinburgh –Bum, the San Diego dog is immortalised in Prince’s Gardens, but he was a stray adopted by a city, there is no tale of faithfulness attached to him. Nor was he the only ‘Cemetery Dog’ of the nineteenth century – Bondeson identifies forty-six such animals, and many of these have their own ‘folk tales’, and statues that attract visitors to these memorials. Yet it is argued that Bobby is probably the most famous of all. He was, and always has been a tourist attraction. Maybe one of the first animals used in advertising, the first of a long line of dogs used in this manner – the Dulux dog and the Andrex puppy being just two that are most recognisable today. These dogs are used to embody qualities such as loyalty and reliability, traits that can be traced back to the little dog from Edinburgh.

If you accept Bondeson’s theory and the interpretation that the tale of Greyfriars Bobby was nothing more than an elaborate advertising strategy, you have to question what aspects of nineteenth-century culture enabled the story to develop in this way.

The year of Bobby’s death also saw the publication of Charles Darwin’s Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. The previous year had seen the publication of The Descent of Man and interest in the sagacity of animals was reaching levels not seen before. Although in no way a new topic, since the publication of The Origin of Species(1859) it had experienced a flourishing amongst both the scientific and lay communities. Newspapers and magazines were regularly publishing articles of anthropomorphised tales of a range of animal behaviours. This anecdotal evidence was collected by the likes of Darwin, and other ‘men of science’ interested in the subject of animal mind.

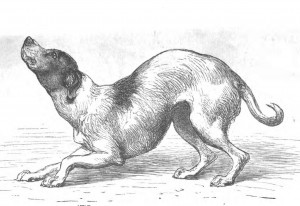

A dog in a “humble and affectionate frame of mind” from Darwin’s book on The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals

The story of Greyfriars Bobby was not one of the anecdotes chosen by Darwin, or George John Romanes (his intellectual successor in terms of the animal mind). Bobby does feature, however, in the work of William Lauder Lindsay. For these three men, all dogs, if treated correctly, exhibited unredoubtable loyalty and love to their owners. All three were themselves dog owners and all professed to have experienced this from their own animals.

Lindsay, in his final book, Mind in the Lower Animals, goes so far as to construct an evolutionary scale based on mental qualities, and places dogs as second only to man. Within this, and his earlier texts on the animal mind, a dog’s ‘worship of man’ is correlated with that of man’s worship of God, and to some extent, woman’s worship of man. Lindsay traces this theory back to Francis Bacon and Robert Burns. That this devotion should continue after death and the animal should been seen to continue their worship is just a continuation human religious practice. Following Lindsay’s reasoning in this way it could be suggested that, even though Greyfriars Bobby’s devotion was greater than some animals (for he lived in the graveyard rather than just regularly visiting the spot), he was not the most devoted of animals. There are many anecdotes of animals being struck by such powerful grief on the loss of their masters that they too died – and surely this is the greater sign of devotion.

The scientific interest in the animal mind coincided with the increasing use of animals within scientific practices – the vivisectional experiments designed to increase the understanding of the physiology of the body, were expanded to include the physiology of the mind. And tales such as that of Bobby were valuable to anti-vivisectional and animal welfare campaigners. Having said that, he was never the figurehead for any of the charitable or legislative movements of his lifetime (Dog Duty Act, 1867; Vivisection Act, 1876), although records show he was made a special exemption to the Dog Duty Act by the Lord Provost. His, now famous, statue on Candlemaker Row was erected to include a drinking fountain for dogs, by Angela Burdett-Coutts, a leading philanthropist and animal welfare supporter.

So, what, if anything, does the story of Greyfriars Bobby tell us? Whether you believe the original tale of a devoted dog mourning his master for well over a decade, or the more cynical version of a publicity stunt that fooled the public for even longer, the answer is the same. Bobby’s story is a microcosm of the way in which the human-dog community was presented in the nineteenth century. The bond between dog and owner was a lasting one, based on a mutual respect. For the men of science mentioned above, dogs embodied characteristics that moral men in society should possess – loyalty, work-ethic, reliability, to name a few. For the animal welfare advocates these characteristics were the reasons that dogs, as well as other animals, deserved to be treated better.

Greyfriars Bobby’s statue stands today as a reminder both of this small dog, the place of dogs within our society, and the deep emotional bond formed between many a dog and their owner.

__________

Follow Liz Gray on Twitter: @lizanngray

Return to: Five Hundred Years of Friendship at the History of Emotions Blog