Dr Katherine Harvey is as Associate Lecturer at Birkbeck, University of London. Here, in a blog post adapted from her paper at the recent SSHM 2012 Conference hosted at the Queen Mary Centre for the History of the Emotions, she explores why tears were such a ubiquitous accompaniment to the activities of medieval bishops.

In his classic history of medieval Europe, The Autumn of the Middle Ages, Johann Huizinga claimed that ‘Modern man has no idea of the unrestrained extravagance of the medieval heart.’ This picture of the Middle Ages as an era of emotional incontinence has been substantially revised in recent decades, not least by the work of Barbara Rosenwein. Nevertheless, many medieval texts do contain far more accounts of powerful individuals engaging in public displays of violent emotion than a modern audience expects.

One of the most common forms of emotional behaviour found in medieval texts is weeping, especially by religious men and women. I am currently exploring the significance of the tears of one particular sub-section of this group: the bishops of late medieval England, with a focus on the twelfth- and thirteenth-century saint-bishops for whom detailed contemporary biographies survive. Without exception, each of these men is depicted weeping, usually with great frequency and incredible volume.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, medieval bishops most commonly wept (or were recorded as weeping) during the course of their religious devotions. Virtually every twelfth- or thirteenth-century English bishop with a reputation for sanctity (whether canonised or not) is said to have wept copiously as he celebrated mass. Archbishop Winchelsey of Canterbury (1293-1313) allegedly wept so much that the altar cloths were soaked with tears. More tears were shed when the bishop was able to pray privately, and most saintly bishops are said to have spent much of their time in tearful prayer. Deathbed tears, associated with prayers and/or the administration of extreme unction, were also a standard feature of the saint-bishop’s life.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, medieval bishops most commonly wept (or were recorded as weeping) during the course of their religious devotions. Virtually every twelfth- or thirteenth-century English bishop with a reputation for sanctity (whether canonised or not) is said to have wept copiously as he celebrated mass. Archbishop Winchelsey of Canterbury (1293-1313) allegedly wept so much that the altar cloths were soaked with tears. More tears were shed when the bishop was able to pray privately, and most saintly bishops are said to have spent much of their time in tearful prayer. Deathbed tears, associated with prayers and/or the administration of extreme unction, were also a standard feature of the saint-bishop’s life.

Why were tears such a marked feature of episcopal devotions during this period? Religious weeping was recorded by hagiographers, and reported in canonisation proceedings, because of the perceived link between tears and sanctity- our sources wanted to show that the bishop had been blessed with the gift of tears. Ever since the Sermon on the Mount (‘Blessed are they that weep now, for they will laugh’), Christians had wanted to weep. The ability to shed copious tears whilst at prayer or at mass could not be taught or imitated, but was granted by God. Such tears proved God’s love for the holy man, and had the capacity to wash away sins. Thus bishops who had been granted the ‘miracle’ of tears, and who could – almost literally – weep buckets, were much admired, and their tears would greatly enhance their chances of being canonised.

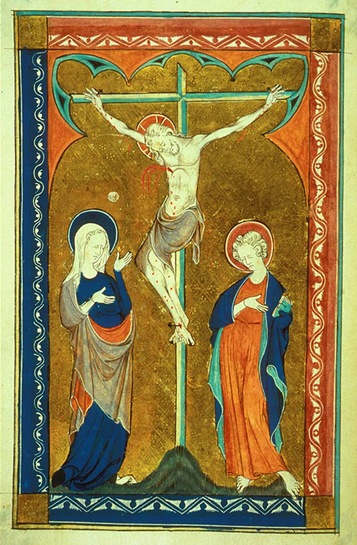

Tears of this kind also relate to some of the key spiritual developments of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Increasingly, emphasis was placed on Christ’s humanity, rather than his divinity, with his sufferings on the cross being a particular focus of devotions. Shedding tears at mass (the ceremony which commemorated the passion) enabled the bishop to demonstrate his identification with God.

Tears of this kind also relate to some of the key spiritual developments of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Increasingly, emphasis was placed on Christ’s humanity, rather than his divinity, with his sufferings on the cross being a particular focus of devotions. Shedding tears at mass (the ceremony which commemorated the passion) enabled the bishop to demonstrate his identification with God.

Ascetic religious practices were also widespread. The saint-bishop, unable to live the simple life for which medieval saints typically yearned, could compensate for his comfortable life in his religious devotions, by privately practising self-denial, and engaging in the mortification of the flesh. Weeping was part of this set of behaviours. Contemporary medical theory stated that excessive weeping weakened the sight, and could lead to blindness. So, by shedding copious tears, the bishop was prioritising his spiritual well-being over his bodily health- but, because most of his weeping was done in private, he was doing so in a way which was compatible with the dignity of the episcopal office. To scourge the eyes in this way was completely appropriate, since sight was widely thought of as a source of temptation. And if the holy man did become blind, then, as in the case of Francis of Assisi, this could be explained through his religious weeping.

Episcopal tears were not all about piety; there also existed a strong tradition of tears as the bishop’s weapons, used to fight in the service of God. Medieval bishops used their weapon-tears in two ways. Firstly, tears were a powerful weapon against temptation by the Devil. Tears of this sort are prominent in the life of St Hugh of Lincoln, who struggled with ‘temptations of the flesh’ for many years, and combated such temptations with ‘the tears and groans expressive of a tormented heart.’ Episcopal tears were also used in defence of the Christian faith and the liberties of the Church. Bishops wept when talking about the threats posed to English ecclesiastical liberties by the actions of the king or the papacy, and when confronted by heretics and infidels.

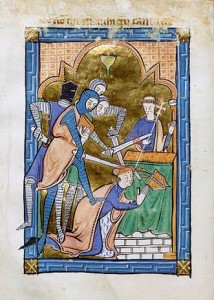

That the bishop’s concern for the church and the faith was sufficient to move him to tears was another indication of the depth of his religious faith. But the presentation of the bishop as warrior had a deeper significance. From the mid-twelfth century onwards, the church required all priests to be celibate- a rule which precipitated something of a crisis in clerical masculinity. Clergymen, who were now forbidden to engage in sex or warfare- the two defining activities of the medieval nobleman- were forced to find new ways to retain their masculine identity whilst complying with canon law. In part, this was done by presenting the cleric as a soldier, but in a metaphorical rather than a literal sense. The chaste life was transformed into a ‘battle for chastity’, allowing religious men to overcome an enemy, and to display military prowess without actually going into battle and shedding blood.

Thus Hugh of Lincoln’s nocturnal tears, shed as the Devil tormented him with sexual temptation, were not signs of weakness, but of strength; they indicated that, although he was a celibate bishop with no military experience, he was also a fully-fledged adult male, armed and engaged in conflict. The bishop’s deployment of tears in defence of the church and faith should be seen in a similar light; the use of this motif allowed him to be cast as a masculine figure, using different weapons (tears not swords) to fight different battles, but still armed and defined by fighting.

In what I have said so far, I may have given the impression that medieval bishops shed an awful lot of tears, and that Huizinga’s account of medieval emotions is not that far from the truth. However, episcopal weeping was carefully controlled, and there were many occasions on which it was emphatically not expected that a good bishop would shed tears.

Tears of self-pity, for example, were certainly not acceptable. Robert Bloet of Lincoln (1094-1123) wept as he contemplated the lawsuits in which he had become embroiled, but he was a courtier-bishop, not a saint-bishop. Potential or actual saints were presented rather differently. When a house belonging to Richard Wyche of Chichester (1244-53) burnt down, his household wept but he did not, for he understood their good fortune: they still had the necessities of life, and should give more alms as a token of their gratitude. Similarly, whilst laypeople might weep at a bereavement, a good bishop would not fear death, but welcome it. He might weep as he prayed for the soul of the deceased, but sorrow could be expressed only if it was feared that the soul had gone to Hell.

Even tears which were shed for good reasons could not stand alone as proof of the bishop’s virtues. In order to make the right impression, tears needed to be accompanied by appropriate behaviour in other spheres- otherwise their sincerity and value might be questioned. The issue of public and private spheres was also key to the interpretation of episcopal tears. Some tears needed to be shed in public, but devotional weeping was best done in private. Hugh of Lincoln (1186-1200) was criticised for engaging in tearful prayer in ‘public places where everyone could see him’, and those who flaunted their piety were often thought insincere.

Despite their admiration of religious weeping, medieval Christians did not simply take those who wept at face value; there was much concern about hypocrisy, and a corresponding willingness to challenge those who were believed to be feigning pious emotions. On the other hand, a bishop’s tears could not be entirely private. By the late thirteenth century, it was virtually impossible for a potential saint to achieve canonisation if he did not possess the gift of tears. Ideally then, a bishop’s devotional weeping needed to be done in a quasi-domestic environment such as his chapel or bedchamber, where his activities would be observed by his closest associates- who would be certain to mention them if canonisation proceedings were opened.

At a distance of several hundred years, it is almost impossible to say exactly what these medieval bishops were thinking and feeling as they shed their many tears. But the thought processes of those who recorded their weeping are much more accessible. For them, tears were certainly not a sign of uncontrolled passions, but a means by which a reputation could be built and secured- tangible proof that their episcopal subject was a model man, a model bishop and, above all, a model saint.

How interesting… I’m currently working on the early Reformation in Poland, and I’ve been struck by the episcopal weeping which goes on in the 1520s and 1530s in that kingdom, both in public and in private, as bishops grieve over the Reformation and schism. The blog certainly helps to put those tears in a longer term perspective.

Pingback: Robert Grosseteste’s Ghost | themedievalbishop