Dr Thomas Dixon is Director of the Centre for the History of the Emotions at Queen Mary, University of London.

Today is the first Valentine’s Day since the House of Commons voted to legalize gay marriage in the UK. An institution, previously the very cornerstone of conventional family life and traditional sexual morality, has been opened to all. Perhaps some will choose today to propose to their beloved – hoping to be among the first same-sex couples to marry in Britain. This blog post offers an historical perspective on this newly state-sanctioned form of romantic love by looking back a hundred and eighteen years to Valentine’s Day 1895.

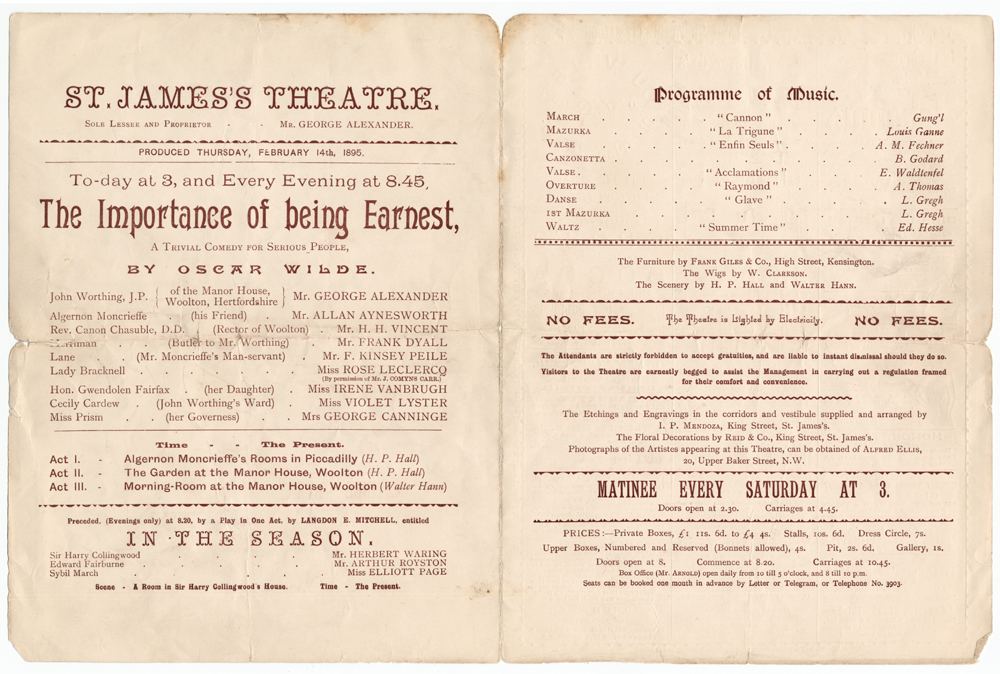

On that day, a new play opened at St James’s Theatre in London – a comedy of love and manners, of marriage and male friendship, with the two leading men eventually exchanging their harmless practice of all-male ‘Bunburyism’ for the more conventional institution of marriage to their lady loves. The play, of course, was Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest. On the opening night, Wilde was called for by the audience at the end of the performance and applauded loudly. The theatre critic of The Times wrote that the laughter of the Valentine’s Day theatre-goers was a sign that this was to be one of Mr Wilde’s most marked successes, predicting that it would be entertaining audiences at St James’s for many months to come.

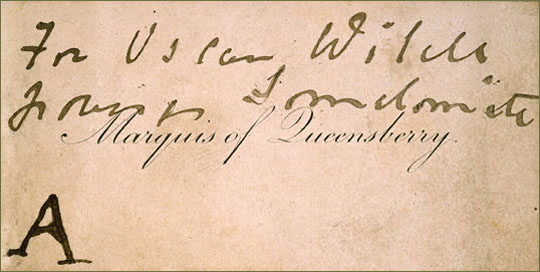

In fact, within four days a train of events had been set in motion which would see the play close, and its author ruined. On 18 February, the Marquess of Queensberry, father of Wilde’s friend and on-off lover Alfred Douglas (known as ‘Bosie’), left a scrawled calling card for Wilde accusing him of ‘posing as a sodomite’. By the end of May, after the collapse of Wilde’s suicidally ill-advised libel action against Queensberry, and after being tried and convicted of committing acts of ‘gross indecency’, Wilde was starting a sentence of two years with hard labour, and his play had closed.

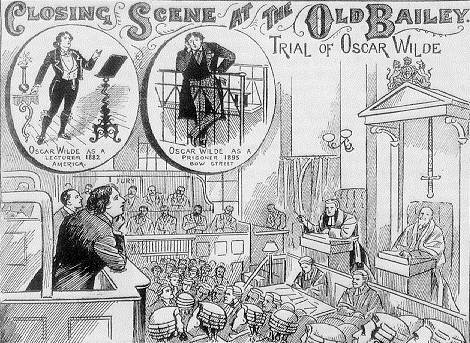

During his criminal trial, Wilde made an impressive and moving speech about ‘the love that dare not speak its name’. This has often been misremembered as an impassioned defence of homosexuality. And indeed just this interpretation was recently reasserted by MSNBC’s Lawrence O’Donnell as part of a short commentary piece on the House of Commons vote in favour of same-sex marriage. Here’s what O’Donnell had to say:

You may have noticed a few ellipses ‘…’ in the quotations O’Donnell showed from Wilde’s famous speech. What did O’Donnell cut out, and did it alter Wilde’s meaning? The short answer is that he cut out all the phrases which don’t fit neatly with our modern ideas about homosexuality, and in the process reversed Wilde’s meaning.

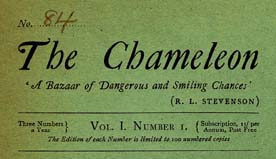

O’Donnell describes Wilde’s speech as ‘honest, and indeed noble, testimony’. I agree that it was noble but I don’t think anyone could claim it was honest. And, for the purposes of those who would cast Wilde as a gay martyr or champion of homosexual rights, it is pretty hopeless. To state it simply, Wilde’s wonderful speech constituted not a brave public declaration of his homosexuality but rather a poetic, intellectualised, and categorical denial of any sexual feelings towards, let alone sexual acts with, other men. The speech – which can be read online at Douglas Linder’s ‘Famous Trials’ website – was Wilde’s answer to a question from the prosecuting lawyer about the meaning of a poem published in a student magazine, The Chameleon, by Alfred Douglas.

Entitled ‘Two Loves’, the verse juxtaposes a personification of ‘true love’, which fills ‘the hearts of boy and girl with mutual flame’ (we might envisage something like that tennis-playing duo pictured above), with another, more shadowy figure who, when challenged replies ‘I am the love that dare not speak its name’. The lawyer put it to Wilde that these figures stood, respectively, for ‘natural love’ and ‘unnatural love’ (in other words, by implication, the kind of sexual instinct that might lead a man towards acts of gross indecency with other men – including rent boys and servants). Wilde denied this vigorously, going on to explain the ‘love that dare not speak its name’ in the words quoted by Lawrence O’Donnell on MSNBC. And also some other words – the ones removed from O’Donnell’s segment.

The cut passages make it clear that Wilde’s intention was to defend not a sexual act, nor a sexual orientation (the former he denied, the latter was not at issue), but a spiritual and intellectual form of affection. Wilde appealed to the biblical story of David and Jonathan to make his point and made it plain that he was speaking about a love that was Platonic (in both senses of that word). The speech with the cut passages restored (in bold) is as follows:

The Love that dare not speak its name” in this century is such a great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep, spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect. It dictates and pervades great works of art like those of Shakespeare and Michelangelo, and those two letters of mine, such as they are. It is in this century misunderstood, so much misunderstood that it may be described as the “Love that dare not speak its name,” and on account of it I am placed where I am now. It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it. It is intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an elder and a younger man, when the elder man has intellect, and the younger man has all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him. That it should be so the world does not understand. The world mocks at it and sometimes puts one in the pillory for it.” (Loud applause, mingled with some hisses.)

There are a couple of points to take from this, beyond mere historical pedantry, I hope. The first thing to say is that it is, of course, no criticism of Wilde to observe that what he did in the Old Bailey in 1895 was something other than outing himself as the first British gay rights activist. Such concepts, aims and identities simply did not exist, and Wilde’s goal was rather to avoid a brutal punishment for his sexual behaviour. If Victorian precursors are to be found for those who, like David Lammy MP, spoke passionately in favour of gay marriage in the Commons recently, they are figures like John Addington Symonds and Edward Carpenter who, unlike Wilde, left extensive writings on the subjects of same-sex love, and sexual identity, and took the first, brave steps towards social reform.

Finally, do we suppose that, given the opportunity, Oscar would have proposed to Alfred Douglas, falling conventionally to one knee and declaring ‘Marry me, Bosie!’ I’m not sure (and anyone who has read the full text of De Profundis would have to entertain serious doubts about the sustainability of the match). Wilde had married once already, and so cannot have been entirely opposed to the institution. But when it came to other men, would Oscar Wilde have been the marrying kind?

Let’s return to St Valentine’s Day 1895 and the first performance of The Importance of Being Earnest. A line delivered by Algernon may offer the most Wildean perspective on all this:

I really don’t see anything romantic in proposing. It is very romantic to be in love. But there is nothing romantic about a definite proposal. Why, one may be accepted. One usually is, I believe. Then the excitement is all over. The very essence of romance is uncertainty. If ever I get married, I’ll certainly try to forget the fact.

Pingback: Feelings, Health, and Cruelty in 19th-Century Divorce Cases | The History of Emotions Blog

Pingback: Love, Pain, Ecstasy, and Murder: An Emotional Christmas | The History of Emotions Blog