Dr Juan M. Zaragoza is a Marie Curie Research Fellow at the Centre for the History of the Emotions, Queen Mary University of London. Here he writes about his current research into the material culture of medical care and the force-feeding of suffragettes.

Last month, The Independent published an article by Arifa Akbar, the paper’s literary editor, entitled “The year of the suffragette: women on the verge of a societal breakdown”. It started with the statement that “Suffragettes are currently having a moment”. To support her point, she provided several examples. The first was the release of Suffragette, the film starring Meryl Streep as Emmeline Pankhurst, Helena Bonham-Carter as Edith New, and Carey Mulligan as Maud – foot soldier suffragettes who become radicalized and turn to violence to achieve their objectives. Akbar also mentioned the release of a new edition of Emmeline Pankhurst’s memories “Suffragette: My own story”, also in January 2015, and the second series of Jessica Hynes’s BBC suffragette sitcom Up the Women. The clip below, from the first series in 2013, gives a flavour:

To Akbar’s list, we can add the forthcoming broadcast on BBC television of a three-part series presented by Amanda Vickery – ‘Suffragettes Forever! The Story of Women and Power‘. This re-emergence of the suffragist movement into the public sphere in 2015 is particularly interesting since, as far as I know, there is not any historical event with a significant anniversary this year, except perhaps for the Women’s March through London on 17 July 1915, sanctioned and paid by the Ministry of Ammunitions, in which the WSPU expressed their support for the war effort and reaffirmed the suspension of their own activities, announced the previous year. Here is a film of the event (without sound) from the British Pathé YouTube channel:

I made my own small contribution to the new ‘suffragette moment’ in early 2015 with a talk on force-feeding, given at the Postdoctoral Research Colloquium at Queen Mary School of History, on which this blog post is based.

As far as we know, Mary Leigh was the first suffragette to be force-fed. Mary and her fellow protesters were arrested and sent to Winson Green Prison, Birmingham, after an action against the prime minister in September 1909. That very same night, Mary Leigh and the other three women went on hunger strike. Four days later, on Sunday 16 September 1909, she was forcibly fed. She recalled that moment as follows:

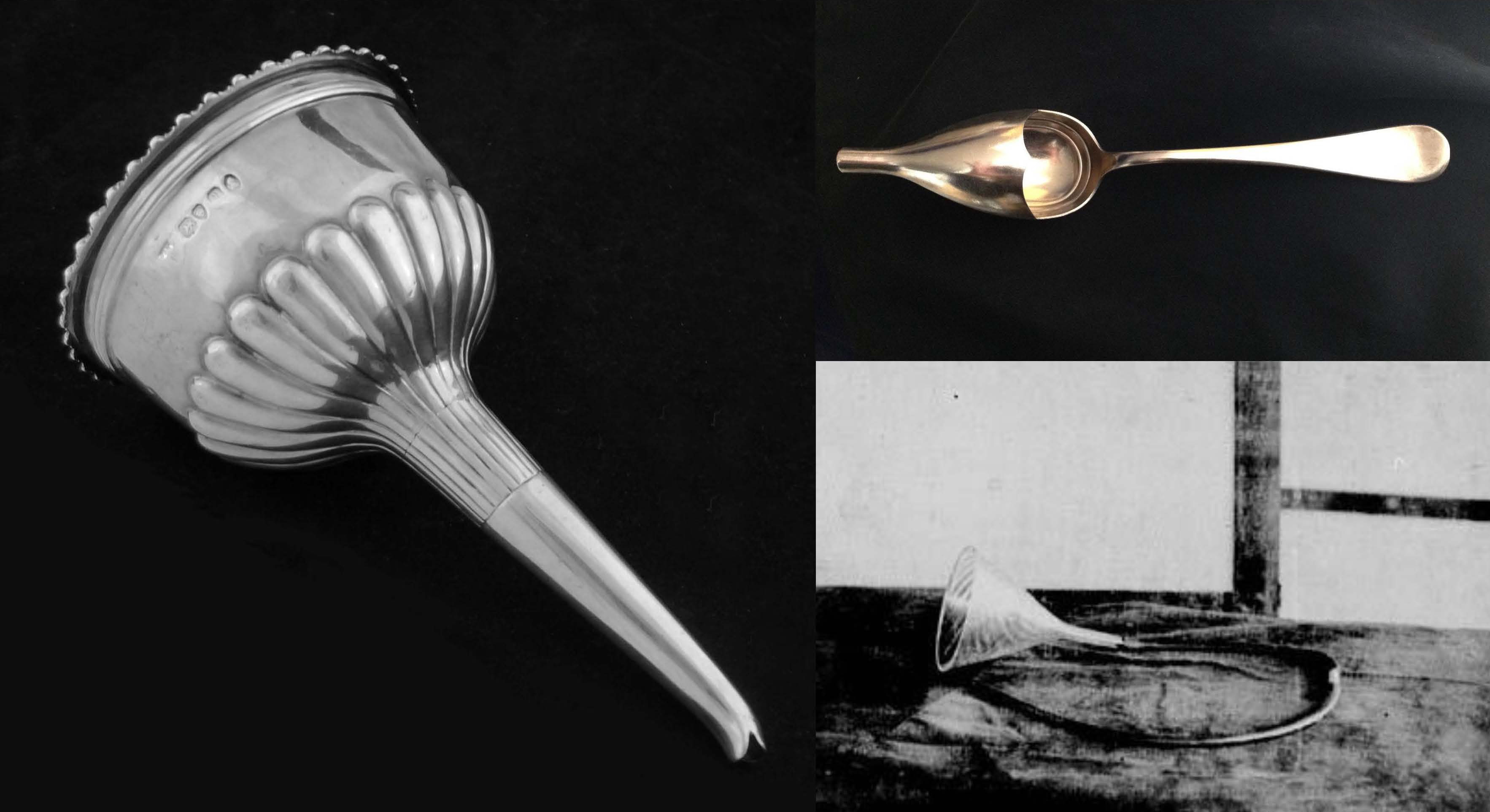

On Saturday afternoon the wardress forced me onto the bed and two doctors came in. While I was held down a nasal tube was inserted. It is two yards long, with a funnel at the end; there is a glass junction in the middle to see if the liquid is passing. The end is put up the right and left nostril on alternative days. The sensation is most painful – the drums of the ears seem to be bursting and there is a horrible pain in the throat and the breast. The tube is pushed down 20 inches. I am on the bed pinned down by wardresses, one doctor holds the funnel end, and the other doctor forces the other end up the nostrils. The one holding the funnel end pours the liquid down – about a pint of milk… egg and milk is sometimes used.

We cannot help being moved and outraged by these lines. Suffragettes’ testimonies to this form of violation became a powerful tool in the movement towards their final victory. The public debate on the issue, and the critiques of doctors and civil servants involved in this form of violence against women, were fundamental for the change of social perceptions of their cause.

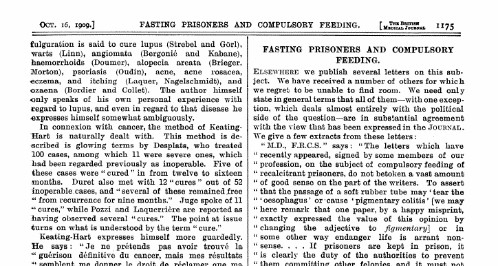

All of this is why what I am now going to ask you to do is difficult – namely to try to understand these shocking events from the point of view of the doctors and nurses involved. Why would I want to do such a thing? The main reason is the distance between doctors’ attitudes then and now – you can compare treatments of the topic in a BMJ item about suffragettes in 1909 and one about hunger-strikers at Guantanamo in the Lancet in 2013. Perhaps a better understanding of this historical attitudinal change can help us to know more about our present values and about the political attitudes towards the role played by medicine in our own culture.

Is it really a problem?

On 28 September 1872, The Lancet published an article entitled, ‘Feeding by the Nose in an Attempted Suicide by Starvation’, signed by a doctor, Anderson Moxey. The author related the death of a prisoner who was on hunger strike “in one of the county prisons”. The motive of his hunger strike was his being sentenced to death for the murder of his wife, of which he had been convicted fifteen days before his death. Dr Moxey said that this death could have been avoided, if only the method of feeding through the nose had been used, instead of through the mouth:

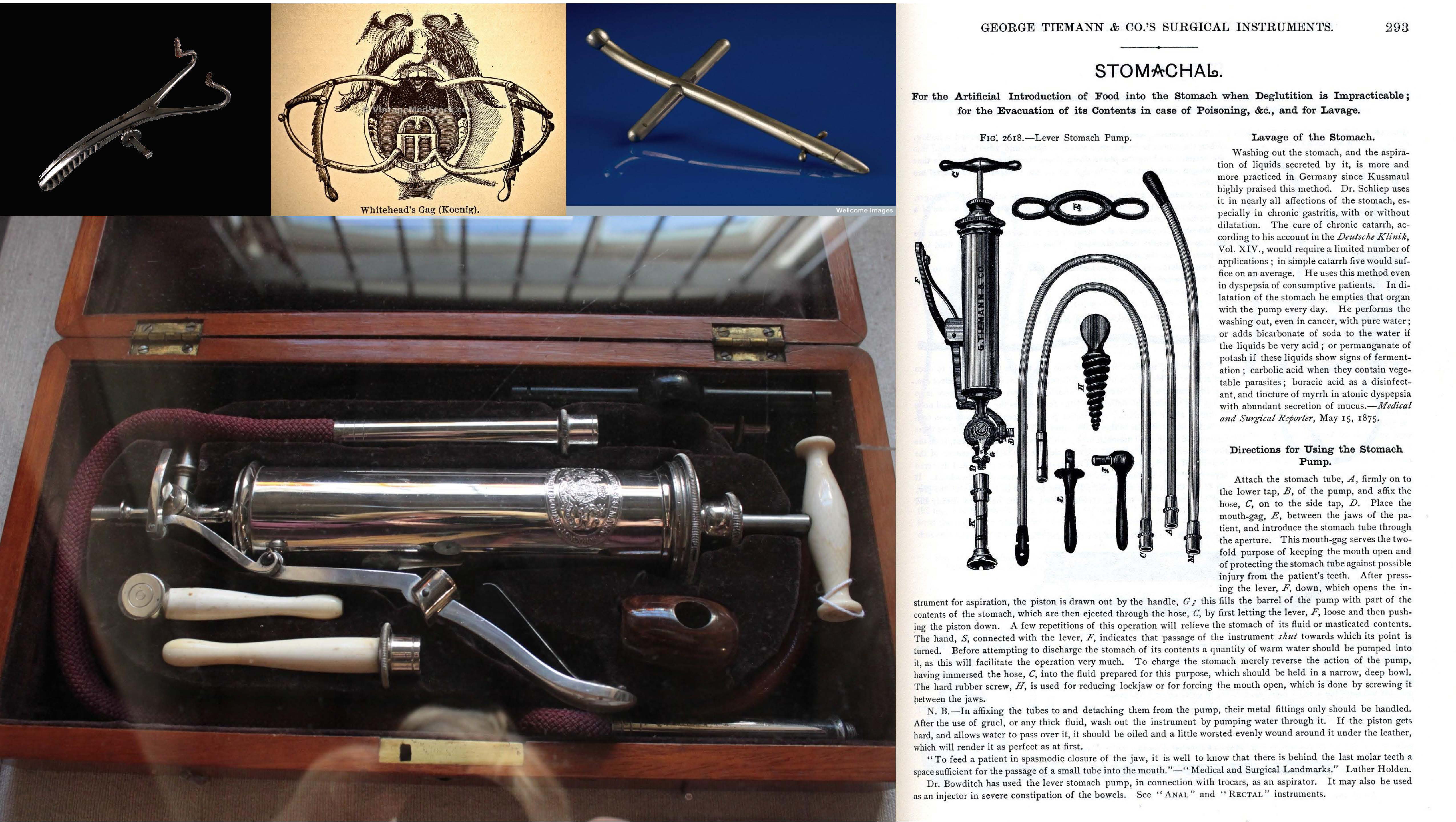

If anyone were to ask me the worst possible treatment for suicidal starvation, I should say unhesitatingly – “Forcible feeding by means of the stomach-pump”[1].

For Moxey, the problem with the forcible feeding of this prisoner was that an erroneous method had been used. If they had fed the prisoner through the nose, by using a funnel, instead of a stomach pump, the prisoner would have survived until his execution date, and justice would have been served.

Does this mean that Moxey avoided passing judgement on the moral problem that this case brought to light? On the contrary! Moxey says that the State should prevent the prisoner from escaping the hand of justice, by any means possible. And no, it is not enough to say that the “torture” produced by the chosen method to feed him was sufficient punishment. The State, says Moxey, should not torture its prisoners, but, again, should serve justice. Justice, in this case, would have been achieved by having chosen the technically correct option, which would have permitted the death sentence to be carried out as it should have been (p. 445).

For Moxey, therefore, the question of the force-feeding of prisoners was just a technical problem. Did other doctors share his opinion?

Moxey is completely wrong

On 30 November 1872, also in The Lancet, a new article was published entitled ‘Forcible Feeding’, signed by the alienist Thomas S. Clouston. He wrote that the method Moxey proposed (feeding through the nose) was “completely contrary to the experience of the majority of doctors who have had to force feed their patients”[2]. Clouston’s attack was direct and devastating. He not only stripped Moxey of any authority to talk about this topic, but he also criticised Moxey’s methods as unprofessional, citing two specific examples: first when Moxey allows himself to quote from memory, and even worse, when he puts words into the mouth of Dr. John Hitchman “which can only astonish those who know him”. (At that time, Dr. Hitchman was the medical supervisor of the Derby county asylum.)

The harshness of Clouston’s attack must at the very least surprise us, given that, in the end, it was provoked by nothing more than a technical discrepancy in how the patient should be fed. And Clouston dedicates the rest of the letter to highlight this difference – as well as to demonstrate his own knowledge of the process. For Clouston, a doctor working in an asylum should carry certain things in his bag (as he will have to face this type of situation many times):

- A common metallic spoon “made of German silver”;

- The ingenious instrument designed by Dr. Stevens (whatever that may be);

- The tube for nasal feeding (“problematic, disagreeable and normally useless”);

- A small silver funnel, with a tube, for feeding through the mouth.

Each one of these objects could be useful, Clouston wrote, depending on the specific case which the doctor face. But the tools for nasal feeding, he wrote, were not to be recommended, for three reasons:

- It is very easy for the patient to resist and to return the food, together with a large quantity of nasal mucus, onto the face and clothes of the physician, and this is disgusting;

- As the tube is very small, the patient can only be fed with very liquid food, ruling out, for example “lamb mashed with a mortar”;

- In cases of an acute manic seizure, portions of food can block the patient’s windpipe.

In other words, what Clouston tells us is that it is a method requiring instruments so badly designed, that it is a risk for the doctor who carries out the task as well as a risk for the patient’s health. Even more, its effect is limited, even when the food is successfully administered.

In comparison to this, Clouston says, we have the gastric pump, which, on the contrary, is widely used and which “has saved thousands of lives” in the simplest way. He describes the method as follows: seat the patient, restrain his hands, open the mouth using a simple and safe instrument, place a gag so that he cannot close his mouth and introduce the tube, without causing damage or pain, through the patient’s jaws.

Care as a technical issue

What we have just seen has not been the cold discussion which we normally associate with a technical debate, but instead a heated argument between supporters of two different methods who aim, it is evident, to show their effectiveness in carrying out the task, but, above all, and I believe this is fundamental, who agree that the vital factor to prove is the effect that it has on the patient. In other words, what these doctors defend, sometimes with such passion, is that the method that they use, “their” method, is that which has the least negative effects on the patient. Negative effects can be avoided thanks to the superiority of different designs, the improved quality of the materials, the use of more instruments.

All this technical debate about the methods of forcible feeding does not make any sense if it is not placed in the broader context of the care of patients within the material culture of the age. At the time – and this is the hypothesis behind my current research – it was understood that taking care of the patient consisted, specifically, in using the material objects that were the most suitable for the particular disease, that improved the patient’s wellbeing and made them the most comfortable during their illness.This is the background that allows the technical discussion to be understood as something that goes beyond the mere functionality of the instruments, beyond whether they are more or less effective.

Suffragists, doctors and politics

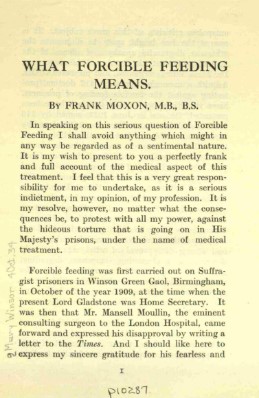

In 1914, Frank Moxon wrote what has gone down in history as probably the most effective attack on forcible feeding in English prisons – a 32-page pamphlet published by The Women’s Press, and available to read online via Bryn Mawr College Libary. Even though it is true that texts appeared prior to this, which denounced the practice against the imprisoned suffragettes, it was Moxon’s account (written while he was doctor in Moorfields), which made the case most effectively.In Moxon’s article we can see how the terms of debate had changed radically since the 1870s. Moxon begins his article by stating that he is going to avoid any “sentimental” approach to the problem, and that his intention is to present a “frank and complete report on the medical aspects of this treatment”. If you don’t want to read the book, I have the perfect audio-visual synopsis of it – an equally upsetting scene from the 2004 film about the struggle of American suffragists, Iron Jawed Angels:

In 1914, Frank Moxon wrote what has gone down in history as probably the most effective attack on forcible feeding in English prisons – a 32-page pamphlet published by The Women’s Press, and available to read online via Bryn Mawr College Libary. Even though it is true that texts appeared prior to this, which denounced the practice against the imprisoned suffragettes, it was Moxon’s account (written while he was doctor in Moorfields), which made the case most effectively.In Moxon’s article we can see how the terms of debate had changed radically since the 1870s. Moxon begins his article by stating that he is going to avoid any “sentimental” approach to the problem, and that his intention is to present a “frank and complete report on the medical aspects of this treatment”. If you don’t want to read the book, I have the perfect audio-visual synopsis of it – an equally upsetting scene from the 2004 film about the struggle of American suffragists, Iron Jawed Angels:

Moxon does not make mention to plastic tubes lubricated with oil, stomach pumps, or funnels. Or, rather, he only does so to describe a violent procedure, which the victims describe as a violation. He does not question the effectiveness of the method (as it had previously been understood in earlier debates) because he is not interested in that issue. What Moxon aims to elucidate is whether the State has the right to force-feed the prisoners. He wants to know if by being imprisoned, as Dr Moxey had claimed, the prisoner is in the same situation as an insane person, having lost the right to decide for himself (p. 13). Moxon is placing the debate in the moment that precedes the problem of efficiency, by formulating a question that we could phrase in the following way: “Does the doctor have the right to decide on behalf of the patient, when the patient cannot?”

But we were already clear on this point, would say the supporters of force-feeding, Pinel gave us a protocol on which to act in the early nineteenth century: we have the adequate tools and our obligation is to look after our patient, to avoid him or her comeing to any harm, even if they are themselves the cause of the harm. Moxon’s reply would be: no, I don’t agree. Artificial feeding (note the subtle difference) is a simple and innocuous procedure, in the majority of cases. What I don’t allow is that we have the right to carry out it against the will of the patient (p. 15).

This change in the terms of the debate did not go unnoticed by the medical profession, and they reacted as a result, either supporting the article (and there were many that did) or, on the other hand, by denouncing it as inadmissible, as it tried to politicise the debate. The latter group, precisely, are those who aim to redirect the discussion back to what they consider to be the appropriate terms. One such example of this was the article published by William Morton Harman, in answer to Victor Horsley’s report published in the British Medical Journal in 1912. Harman placed the debate where he thought it should be, not in the political interpretation of Horsley (and Moxon), but in the technical questions discussed by Moxey, Clouston and others.

To conclude

The debates about forcible feeding at the end of the 19th century should be placed within the context in which the care of the sick was understood at the time, which paid special attention to the material elements. When you track the debates around the issue, you realize that these doctors never questioned if they did or didn’t have the right to feed someone who didn’t want to b fed. Or, rather, if they did, this only served to confirm that they did have this right, as only in this way would they prevent the death (by suicide) of their patients. Once this was decided, the remaining steps were to establish the protocol and to develop the most effective and the least harmful techniques possible. What Moxon and others proposed, therefore, was a total correction to how doctors understood their jobs, their relation with their patients and the primacy of “care” as the backbone of medical practice.Without a doubt, the suffragist movement pushed the medical profession to change, as it also pushed other institutions and forms of social organisation to change.

I know the topics of suffragists, violation and hunger strike are highly controversial. To avoid any ambiguity let me state my view that the suffragists, Moxon, Horsley and the others were right. Doctors didn’t have the right to choose for their patients whether or not they should be fed. Nor do doctors have that right today. Suffragists described forcible feeding as a violation because it was a violation, and the doctors were guilty of an attack on women. My goal is to understand how it was possible that a great part of medical profession supported the government, but not to justify them!

References

[1] D. Anderson Moxey, “FEEDING BY THE NOSE IN ATTEMPTED SUICIDE BY STARVATION.,” The Lancet, Originally published as Volume 2, Issue 2561, 100, no. 2561 (September 28, 1872): 445, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)56483-7.

[2] T. S. Clouston, “FORCIBLE FEEDING.,” The Lancet, Originally published as Volume 2, Issue 2570, 100, no. 2570 (November 30, 1872): 797, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)56739-8.