Dr Matthew Klugman is an Australian Research Council DECRA Fellow at Victoria University (Melbourne, Australia) where he researches and teaches on the intersections of sport, passions, bodies, gender, sexuality, religion, migration and race. He is currently studying the emergence of modern spectator sport cultures in Melbourne, Manchester and Boston, and in this post, published to coincide with the emotional climax of the 2015 English football season, he reflects on the first emergence of football mania well over a century ago…

Dr Matthew Klugman is an Australian Research Council DECRA Fellow at Victoria University (Melbourne, Australia) where he researches and teaches on the intersections of sport, passions, bodies, gender, sexuality, religion, migration and race. He is currently studying the emergence of modern spectator sport cultures in Melbourne, Manchester and Boston, and in this post, published to coincide with the emotional climax of the 2015 English football season, he reflects on the first emergence of football mania well over a century ago…

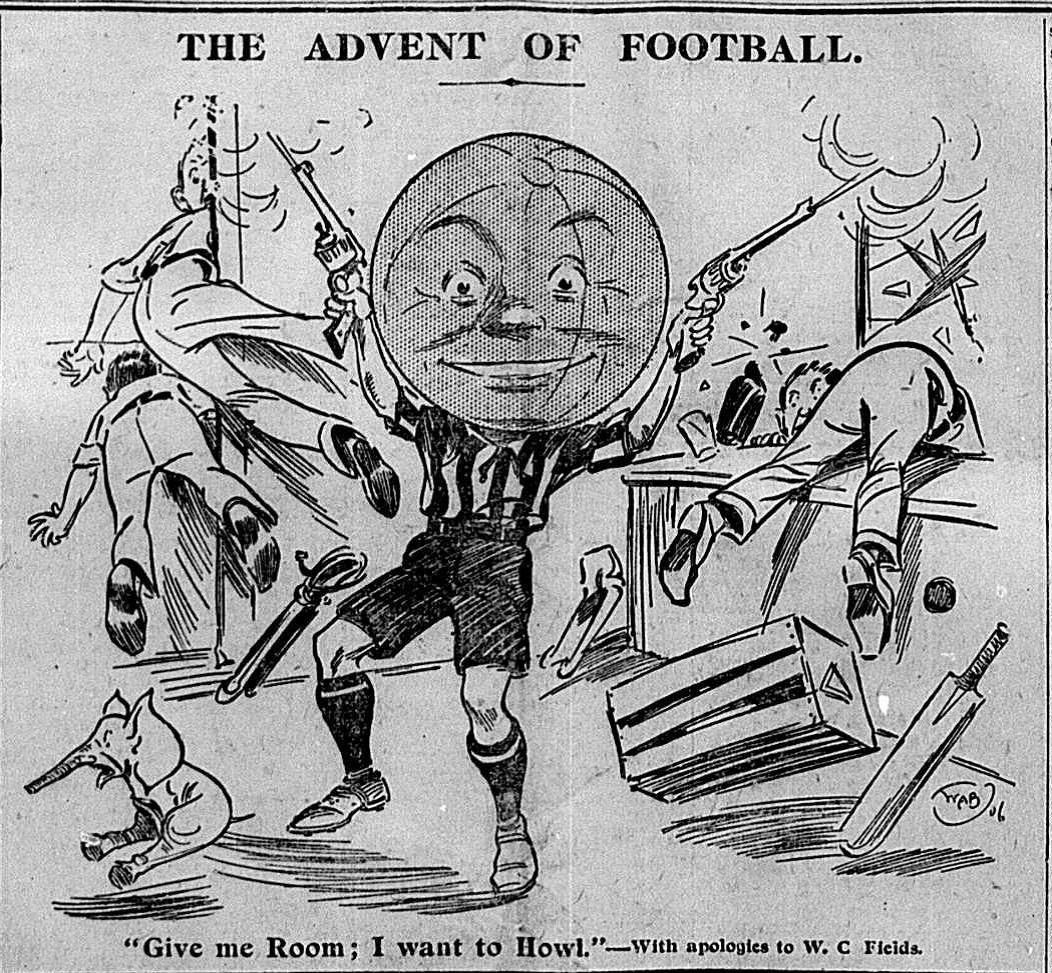

A 1906 cartoon captures the way the new rowdy emotionalism of Association football was challenging the more genteel style of cricket spectatorship.

“No one who does not know the North of England”, noted Bristol’s Western Daily Press to its southern readership in 1893, “can have any idea of what the football mania is.” The Western Daily Press was reporting on a talk that the Archdeacon of Manchester, James Wilson, had given regarding “The Education of a Citizen.” The paired topics of football and education might seem surprising, but from 1859 to 1879 Wilson had been the Master of Maths and Science at Rugby – the public school most associated with the promotion of athletic endeavours as a means of turning boys into disciplined, healthy, courageous, and strong Christian men. In keeping with this, Wilson’s 1893 talk emphasised the need for children to undertake “athletic exercise” in order to create citizens with “strength, vigour, and health”, upon which the “wealth of the nation depended”. But for Wilson Association football was not building strong, upright citizens. Instead, it was facilitating a dangerous “rage” for “athletic spectacles” that left spectators weak and impoverished.

The mid-to-late 1800s saw the development of modern team-based spectator sports – like the football codes – which developed into institutions of considerable cultural, social and economic power. Historians have tended to view the development of these sports as allied to processes of industrialisation, puritanism and functionalism, with sports becoming another tool for controlling and regulating bodies. Association football, for example, can be seen as an emblematic Victorian sport. The wildness of violent village games was replaced by a codified contest played on a field with clear boundaries, in a manner described as “scientific”, while the expansion of the game depended on the developing railway network, and the spectators who flocked to it were partaking in an emerging culture of leisure. However, the fervour that marked these spectators has largely been passed over. Recurrent phrases such as “football mania” have been analysed as reactions to an evolving working-class culture around football, but the particular “emotional” culture that came to characterise football has been neglected. Yet this culture sheds light into other aspects of Victorian life – the interlinked fascination with, and suspicion of, emotions, the concern with the new diseases of modern life, and the way so-called pathologies might be celebrated as well as critiqued.

The evolution of the phrase “football mania”, for instance, reveals a growing interest and concern with those who began to follow football games. After emerging in Britain in the mid-1870s as shorthand for those playing football – either with great enthusiasm, or in a way that created a public nuisance – the phrase was quickly extended to include spectators as well as players. In 1878, for example, a lengthy report in London’s Morning Post, noted with Victorian reticence that “in the Midlands and Northern counties the interest taken in representative contests is little short of enthusiasm” while “North of the Tweed, the football mania, as it may almost be termed, is still more dominant.”

By 1887 the focus was turning more to the spectator culture, and there was no “almost” in the critique that the Reverend Joseph Parker of the Congregational City Temple in London, gave to a group of Glasgow Clergyman when he visited Scotland. Parker had looked for religion in the daily papers only to finds columns regarding football. “He asked if all the world was mad, and all the men and women football players”, before going on to note that “he had had seen great excitement manifested at a railway station on Saturday. He asked if the Queen was dead or St Paul’s burned to the ground? No, it was a whole community gone out after football.”

While Parker seemed primarily concerned with the way football was coming to mean so much, others were more specific in noting the aspects of this culture that they disliked. Towards the end of the year the Lancet published a review that was highly concerned with the physical dangers of football. In response, the Edinburgh Evening News praised the physicality and courage needed to play the game, arguing instead that the main problem was the way “a manly game” was being “turned into a nuisance by excessive devotion”, with the consequent “football mania” having a deleterious effect on the character of public lectures and the support of Mechanics institutes and related bodies.

There is an implicit opposition here between the manly deeds being performed on the pitch and the significantly less manly behaviour of those watching the courageous players. Spectator sports (and especially the football codes) have long been critiqued for upholding what has become a hegemonic version of aggressive masculinity – celebrating strong men willing to put their bodies at risk and to bruise and batter their opponents. Yet there is a hint here that the emerging spectator culture could also foster a more heterodox masculinity, one that involved not being courageous and manly themself, but rather becoming excited by, and devoted to, those men who performed bravely for their entertainment. And this raises questions then as toward the gaze of these male spectators who could become so excited by watching these (other) men play.

The defenses of football culture could be as revealing as the critiques. After the first game of the 1889-90 football season the Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette felt compelled to admonish the growing critics of the so-called football mania who were apparently prophesying that the madness for football would never last:

… we already hear the sneerers talking about the ‘football mania’. At the close of the last season these critics indulged in predictions that the ‘madness’ had about run its course, and that in all probability it would suffer from reaction in 1889-90, and then die out, leaving a sense of self-astonishment in the men, women and children who had lost their heads over the ‘absurd pastime’. At the first summons of the season about twelve thousand people declared last night that they were quite as mad as they were last season. And we shall probably find as the months pass, as we found last year, that the sneerers will gradually become mad themselves. We know of several very steady-headed critics of the ‘mania’ who bethought themselves that they would just go and see how utterly foolish the whole thing was, They went, and gradually became afflicted with that lesion of the intellect which they had predicated of others.

One of these sneerers – a well known gentleman – had to offer many apologies in the course of an hour and a half for kicking the shins of spectators near him, the lesion of intellect having progressed so far on a first inspection of the game as to lead him to imagine that he was somehow engaged in the match. Another of the same class, being carried away by the prevailing and very contagious enthusiasm, and having dropped his hat, so forgot himself as to seize the hat of another person in order to wave something when the local team had scored a difficult goal.

Yet while the Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette admitted “a certain degree of madness, if British enthusiasm for physical prowess be it nevertheless defended the “popular pastime” of attending games as actually “a powerful auxiliary to the temperance reformer” that limited the amount of drinking those attending games would otherwise indulge in on a Saturday afternoon. The conclusion was that the notional madness had rational benefits:

when one sees ten thousand people with glistening faces at a football match, one feels that such excitements are worthy of praise rather than condemnation. Moreover, the infection of the manly game, spreading to the rising generation, has a beneficial result in the promoting of that physical development which ought to be part of the education of British youth.

This piece is a useful source partly because of the rich way it chronicles the physical culture of spectating – the kicking of others because one identifies so much with the players it feels one is on the field, the need to wave hats in the air to express the great  joy of seeing a goal scored by your team, and the thousands of glistening faces. But the relative sophistication of the playful use of medical terms is also revealing, and there is a need to locate this within the broader culture of deploying medical terms, especially but not only, the very popular Victorian term ‘mania’. Recent histories of mania by Emily Martin and David Healy have traced the connections that many people made between states of manic euphoria and stupefying melancholia – connections that laid the foundation for later understandings of manic depression.Yet there no such links are made in these popular accounts of football mania. The focus lies solely with the intense enthusiasm, excitement, joy and obsession, not the considerable sadness and mourning of defeats that was already a part of football culture.

joy of seeing a goal scored by your team, and the thousands of glistening faces. But the relative sophistication of the playful use of medical terms is also revealing, and there is a need to locate this within the broader culture of deploying medical terms, especially but not only, the very popular Victorian term ‘mania’. Recent histories of mania by Emily Martin and David Healy have traced the connections that many people made between states of manic euphoria and stupefying melancholia – connections that laid the foundation for later understandings of manic depression.Yet there no such links are made in these popular accounts of football mania. The focus lies solely with the intense enthusiasm, excitement, joy and obsession, not the considerable sadness and mourning of defeats that was already a part of football culture.

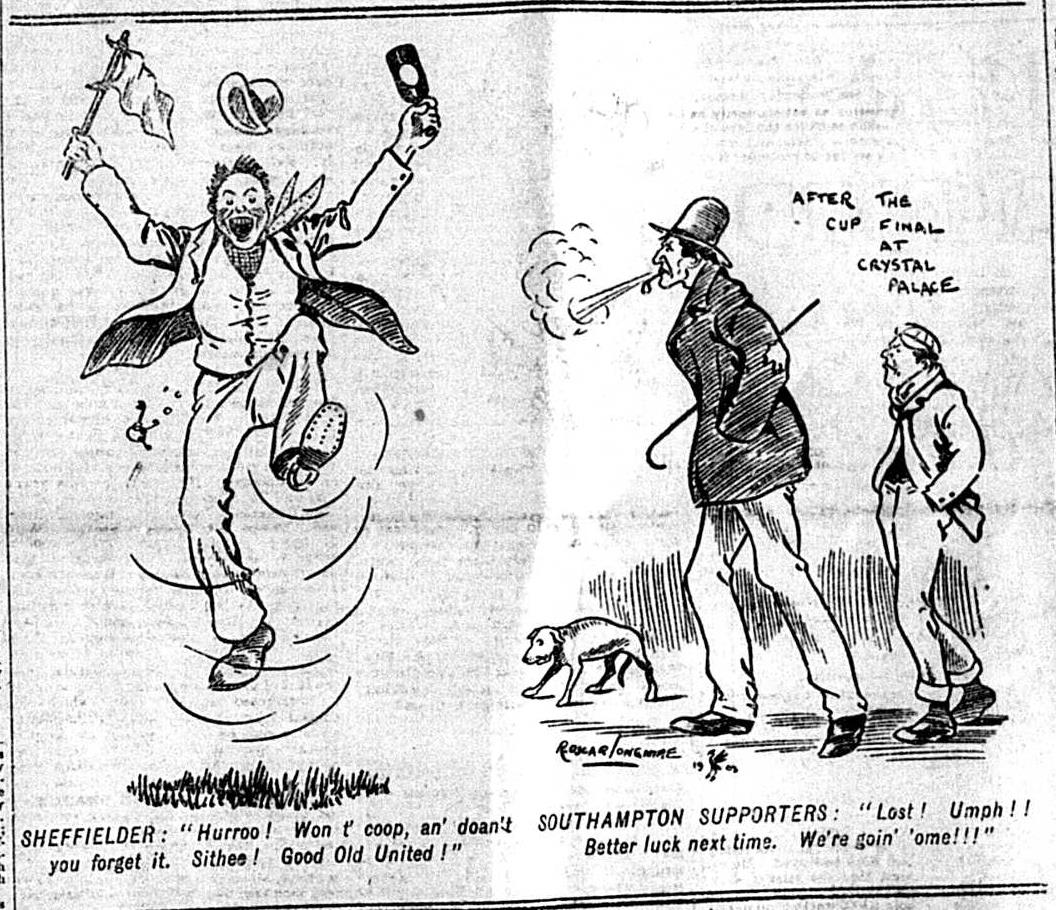

This Umpire cartoon after the 1902 FA Cup final, for example, contrasts the excessive exuberance of a winning Sheffield supporter with the grumpy demeanour of two well-to-do Southampton followers. The caricatures speak to presumed class differences, but it is also notable that while the celebrations of the “Sheffielder” are depicted as manic as he celebrates a victory that should not be forgotten by drinking and dancing himself into oblivion, the displeasure of the men from Southampton is rendered reasonable and contained by stiff upper lips. Yet in the immediate aftermath of the match the president of the Southampton Club had stated that “We are bitterly disappointed at not getting the Cup”; an intense and seemingly absurd expression of dismay at the failure to win what was still just a game.

Despite the Victorian fascination with mania, it was much rarer for the other popular sports of this time – such as cricket, horse-racing, pedestrianism and lacrosse – to be associated with mania by ministers of religion or journalists. Moreover, the intimations and even claims that there was something pathological about following football were made by some medical experts as well as lay figures. In 1906, for example, the famed British doctor Sir James Crichton-Browne wrote that:

The inordinate addiction to football watching becomes a kind of psychical intoxication. Those who habitually indulge in it are apt to become stupid and sodden, or silly and frenzied. A little of it is exhilarating, too much of it, to the exclusion of other interests, must weaken the brain. A variety of impressions is necessary to cerebral vigour. The incessant repetition of one small round of ideas debilitates – and so football may become almost a monomania.

For some Christian ministers the pathology continued to be one of misplaced meaning. In 1892 the Scottish evangelical preacher John McNeill noted that ministers he met were “groaning and lamenting at the ‘eternal fitba’” because not only did whole communities seem to go to the game:

they had to talk it over again, and if it had ended there it would not so much matter. But it did not. On Sunday they were as much possessed as ever; they stood at street corners and took a walk in the country and talked the whole match over – every kick being kicked again, and every man’s merits being canvassed.

A year later, and Bristol’s Western Daily Press used James Wilson’s talk to expound on the lamentable way those in the north of England carried “their love of sport to the point of ridiculous excess”:

Everyone, as it seems to a visitor to a northern town, above the age of a schoolboy thinks more of football than of anything else. Professional players, generally artisans hired for the season by the club that can pay them best, are the heroes of the day. Their play and their physical condition are gravely discussed by thousands of people, and affairs of State are of no importance at all in many people’s eye compared with the probability of their club winning its cup tie… one wonders however [how] the class of people there could afford the money [to attend games]. But they do, and they can find money also for the newspapers that live on football.

Perhaps one of the reasons that such critiques of “football mania” have been passed over is our familiarity with the culture of apparently absurd meaning being attributed to cup ties and other football contests. Another aspect that seems familiar is the deployment of religious terms such as devotion and possessed which hint at the metaphor of spectator sport as religion that was soon to take hold. This metaphor was used directly by the Sunderland Gazette and Shipping News in a note below their report of Wilson’s critique. While their headline for the report of Wilson’s lecture was “Plain Words from a Parson”, right below it was the headline “Football a Religious Rite” with the humorous column observing how appropriate it was that a public lecture about the 1893 FA Cup was held in a Manchester church.

If the excessive fascination with football contests was a modern disease, then it seemed to be a pathology that also threatened the place of religion in the lives of football devotees. And while it is important to be aware of the dangers of “presentism”, it is nonetheless of interest that metaphors of mental illness and religion continue to shape contemporary descriptions of spectator sport cultures. The challenge now is to research and write back in the multifarious, often difficult and yet also seductive pleasures that these sports provoked in spectators – pleasures that provoked accusations, and celebrations, of mania, and which drove the development of these sports into such powerful cultural, social and economic institutions.

Follow Matthew Klugman on Twitter: @Raw_Toast

This research project is supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Research Fellowship (project number: DE 130100121).