Evelien Lemmens is a PhD candidate on the ‘Living with Feeling’ project, starting at Queen Mary University of London in September 2016. Her research will focus on the relationship between diet, digestion and emotional health in Britain and the Netherlands between 1850 and 1950.

Mental and emotional health are increasingly prominent topics in our media and public debate. The list is endless: the vigorous interest in stress and Mindfulness; a call for emotional education in schools; a surge in healthy eating and the gut as ‘the second brain’.

The workshop was attended by academics and senior practitioners from a range of disciplines from history to neuro-gastroentology, who were asked to present three words associated with ’emotional health’. Reflective of personal and professional interests, the replies varied. Some were optimistic (joy, laughter, life), some neutral (resilience, self-control, balance), others scientific (vagus nerve, ghrelin), and others pessimistic (the state, control, the media, anger). ‘Emotional health’ is clearly open to interpretation.

The ‘What is Emotional Health?’ workshop marked the start of Queen Mary’s ‘Living with Feeling’ project, which will conduct interdisciplinary research into the history of emotional health from 1600 to present. The research will hone in on three overlapping meanings of ‘emotional health’: the emotional dimensions of the medical encounter; the emotional factors influencing physical and mental health; and emotional flourishing.

The first approach considers the emotional dimensions of the medical encounter between patients and doctors, including the roles of empathy and compassion.

Medicine – as embodied by white-coated doctors and disinfected hospital wards – is often presented as a haven of rationality, promising cleanliness not just in its physical spaces but also in its approach and diagnosis. The presumed result is an unbiased – and indeed unemotional – diagnosis.

In contrast, the Emotional Health workshop highlighted the emotions in medicine, especially the emotional wellbeing of doctors and patients. Oncologist Sam Guglani, in a column entitled ‘Feeling’, posits that caring for others, “fellow-feeling”, is at the core of doctors’ morality. Is it this heightened emotional sensitivity that draws them to medicine in the first place? He argues that the demand on doctors to respect – at times unclear – professional and emotional boundaries between themselves and their patients results in a vacillating between “emotional silence” (resilience) and “high displays of sentiment” (compassion), neither ideal nor emotionally fulfilling.

Image credit: http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2015/03/19/doctor-photo-grieving-dead-patient_n_6905290.html

The photo to the left, which went viral in March 2015, captures the growing attention for the emotional demands on doctors and their coping strategies. This distraught EMT privately grieving the death of a 19-year-old patient prompted an outpouring of empathy online. The Internet praised his professionalism, for ‘holding his head high’ afterwards, perhaps showing that while empathy is welcome, emotional self-control remains a must.

The question remains: how much emotion should a ‘good’ doctor feel (felt aspect) and show (performative aspect)? This social construction of the ‘ideal’ doctor is historically contingent and subject to historical research, such as that by Alison Moulds, which focuses on the construction of the doctor-patient relationship and the formation of a professional identity in the nineteenth century.

Aside from doctors’ emotional health, the patient’s medical experience – from symptoms to diagnosis and treatment – is also heavily laden with emotion, as is clear from work undertaken at the Health Experiences Research Group at the University of Oxford. This project has traced individuals’ personal and emotional experiences during 94 illnesses to date, from adolescent skin conditions to chronic pain, and cancer.

Medicine – as an interaction between doctors, patients, symptoms, diagnosis and so on – is a hotbed of emotion. Even in dealing with physical illnesses (as opposed to mental illnesses, though the dichotomy is flawed), feelings of anger, fear, joy, and gratitude satiate the air of hospitals.

The second approach focuses on the emotional factors influencing physical and mental health, focusing on emotions as contributory factors to both illness and wellness.

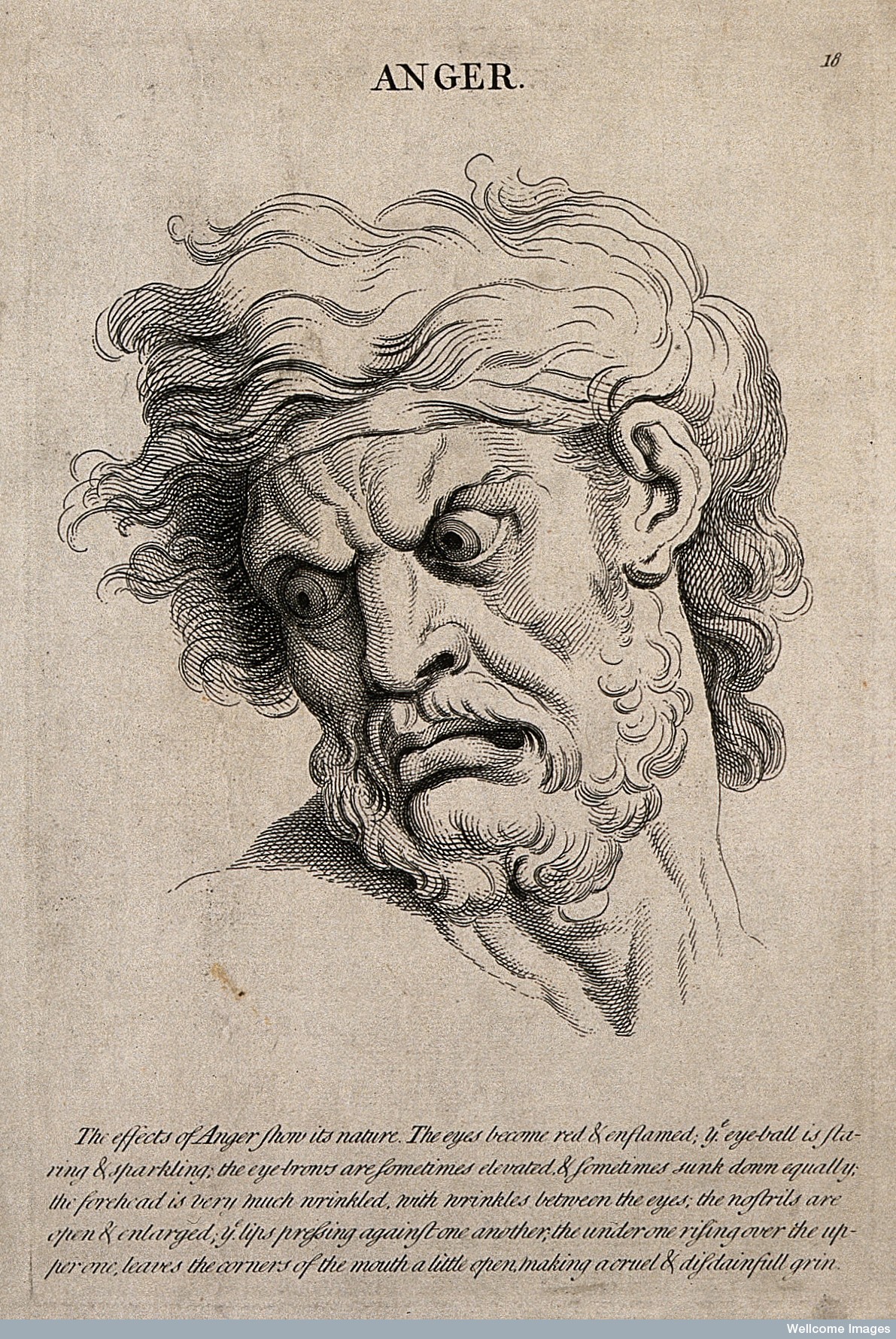

In scientific, philosophical, literary, didactic, and colloquial source material, historians can trace an established relationship between emotions and the body – both external, in physiognomy for example, and internal. The exact understanding of the impacts of emotional states on the heart, stomach, bowels and so on have evolved.

Contributions from modern neuroscience prove crucial into understanding emotional states, underlining the role of hormonal and biochemical processes. Take adrenaline in anger and cortisol in stress: the production of both is a biophysical reaction to a specific situation. However, different historical spaces – geographically, chronically, and societally – have been characterised by unique socially-constructed emotional standards. This reveals a key premise on which the history of emotions is based: emotions and emotional experiences have both a biological element and a socially-conditioned element.

In terms of specific emotional states, much of the discussion focused on ‘anger’, Thomas Dixon’s latest research project. By positioning Darwin’s ‘animal anger’ against Aristotle’s ‘moral anger’, it is clear that this emotion can be interpreted either as a primitive, animalistic reaction or as a justified and morally-correct response. There is indeed a self-righteousness to anger – the individual’s notion that they are morally superior in a situation and therefore have the right to be angry. At what point is the internal feeling of anger allowed to be translated into external aggression, and is keeping emotions pent up inside actually worse for the individual’s health?

The third aspect focuses on ‘Emotional flourishing’, understood as a state of healthy balance in an individual’s emotions.

‘Emotional flourishing’ proved to be a term both helpful and problematic. Is emotional wellbeing something that some people have, and others do not? And what should we feel to be emotionally at our best?

Jules Evans’ research focuses on the role of ecstasy in our society, where an ecstatic experience is understood as a moment where you go beyond your ego-consciousness to feel a connection with something bigger. In The Art of Losing Control he observes a modern societal obsession with the Ecstatic: from travelling the globe in search of ecstatic experiences to the ecstasy experienced around weekends and sporting competitions, we have become obsessed with the Ecstatic. In contrast to his initial hypothesis that we needed more ecstasy, the opposite is true: society needs a better balance; a happy medium instead of long troughs of the mundane followed by short-lived peaks in our emotional lives.

This echoes with a recent call for “emodiversity”, which encourages individuals to experience a wide range of emotions, rather than focusing solely on the traditional Western “pursuit of happiness.” A healthy “emotional ecosystem” is one thriving with diversity.

Stefan Priebe emphasised the social nature of emotion, arguing “life is about emotion in a social context.” It is difficult to understand certain emotions without a social context: love, gratitude, disappointment and envy are feelings instigated by the actions of a second individual. There is a need for further research into the effect of emotions on the quality of social networks, as well as a need for vigilance when studying inherently social emotions with only an analysis of the individual.

Imitation and emotional contagion were widely discussed on the day, a topic that Tiffany Watt Smith will research the development of, from 1800 to present. The nineteenth century was marked by an “Early-Victorian disgust of imitation,” argues Tiffany, when it was believed individuals were taught to suppress the primitive instinct to imitate others that they were born with. However, research such as that by developmental psychologist Caspar Addyman has further demonstrated the absence of imitation in babies aged 0-2, arguing that imitation is a learned response.

This is where the perceived importance of education, both historically and today, deserves a mention. During discussions neuro-gastroentologist Qasim Aziz pinpointed that though there is a serotonin transporter gene that can be inherited and shows links with depression and neuroticism, education and upbringing are a crucial factor in emotional wellness. This is not a new argument: “A very considerable preservative against both bodily, and mental Ills, is without doubt a good Education,” wrote Charles Collignon in 1794.[1]

As scientific understanding of the body and emotions permeates the walls of academia into the public sphere, public engagement becomes ever more interesting and crucial. In June 2016 the Queen Mary Centre for the History of the Emotions organised the Carnival of Lost Emotions, which encouraged the public to engage on topics of emotional talismans, historically-specific (and today obsolete) emotional states, and emotional facial expressions. The next public engagement project lined up is ‘The Museum of the Normal’, to be held in November 2016. As the name suggests, the project will tackle the public’s hopes and fears around “being normal”, both historically and present-day.

Find out more about the ‘Living with Feeling’ project on our website.

[1] Charles Collignon, An Enquiry into the Structure of the Human Body, Relative to its Supposed Influence on the Morals of Mankind (Cambridge: J. Bentham, 1764).