Depression is the leading cause of ill-health worldwide, but therapy is little known or practiced outside the West. If psychotherapy is going to become more popular in the non-western world, it needs to build bridges and find cultural parallels in local spiritual traditions. This is totally doable.

Depression is the leading cause of ill-health worldwide, but therapy is little known or practiced outside the West. If psychotherapy is going to become more popular in the non-western world, it needs to build bridges and find cultural parallels in local spiritual traditions. This is totally doable.

The UK has had a good last decade when it comes to mental health awareness. The Brits don’t talk about our emotions? We never shut up about them these days! Not a week goes by without some official or celebrity – Theresa May, Prince Harry, Rio Ferdinand – saying we need to talk more about mental health. That’s a good thing. It’s good to talk, though it’s even better when that talk is backed up by increases in government spending on mental health services.

The situation is a lot worse elsewhere. As the World Health Organization highlights today in its World Health Day campaign, depression is now the leading cause of ill health and disability worldwide, affecting more than 300 million people. While only around 50% of people with depression get therapy or medication in high income countries, in middle and low income countries, the percentage is closer to zero.

In half the countries in the world, there’s only one psychiatrist per 100,000 people. In India, where I spent the last three months, the country spends 1% of its GDP on health (the OECD average is 9%), and 0.1% of that on mental health services – one of the lowest figures in the world. There’s one psychiatrist for every 300,000 Indians, though in fact most psychiatrists are based in the big cities. In poorer rural regions, there might be one psychiatrist for every million people.

There’s a lot of stigma around mental illness around the world, and little awareness of psychotherapy. And there’s a cultural and language problem for both psychiatry and psychotherapy. Sadia Saeed Raval, who runs the Inner Space therapy centre in Mumbai, says: ‘Therapy in India is mainly Anglophone. The training is in English, the terminology is English, and the therapy techniques tend to be developed in the West.’

At a recent event I attended on mental health in India, the discussions were almost all in English, and even when a psychiatrist spoke in Hindi, he still used English words like ‘stigma’ and ‘depression’. The WHO’s own campaign posters, ‘Let’s Talk’, are also all in English. Imagine if we in the UK only had Indian words for depression, anxiety or other internal states.

This Anglicisation of therapy has limited its cultural dispersal in low and middle income countries to affluent, westernized elites. So how does everyone else cope with mental illness? In large part, by turning to religious or spiritual healing. This might sometimes work – it can help provide meaning, community support, meditation, and the powerful placebo of hope. But it doesn’t always work, and in some cases can be harmful.

What to do? Obviously, the best thing would be for countries to increase their spending on mental health services. I imagine the WHO is trying to get its member states to do that. But we shouldn’t assume that western psychiatry has all the answers to the meaning of life (look at suicide rates, where some Western countries do worse than many non-Western countries).

We can also try to help bridge the cultural gap between western psychiatry and psychotherapy, and non-western cultures. And here the medical humanities can help.

In the UK, the most popular and evidence-based therapy for depression and anxiety is Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). As I and others have researched, CBT has its roots in the ‘healing wisdom’ of Stoicism and, to a lesser extent, Buddhism.

That means that it is easily translatable into other cultural contexts, because the idea of ‘healing wisdom’ appears not just in Greek philosophy but also in Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, Jainism and many other religious and spiritual traditions. Indeed, Stoicism was a big influence on therapeutic wisdom books in Christianity (Boethius’ Consolations of Philosophy, for example) and Islam (eg Al-Kindi’s On Dispelling Sadness).

There is also a great deal of similarity between Stoic-CBT therapeutic ideas and those found in the wisdom texts of Hinduism and Buddhism. For instance, Stoicism / CBT is based on Epictetus’ idea that ‘it’s not events, but our opinion about events, that cause us suffering’. Likewise, the Buddha taught: ‘We are what we think. All that we are arises with our thoughts. With our thoughts we make the world’.

Many different wisdom traditions recommend learning detachment, both from one’s own thoughts and desires, and from the ups and downs of fortune, and learning to accept the limit of one’s control over the world – both of which are central concepts in CBT and Positive Psychology. Many also recommend some form of mindfulness and techniques for improving it – Stoicism-CBT recommends keeping track of your thoughts and behaviour in a journal, Jesuits practice ‘recollection’ at the end of the day, Orthodox Christians practice ‘nepsis‘ or watchfulness, and so on.

Many different wisdom traditions emphasize that changing the self takes repetition and practice (askesis in ancient Greek), as CBT does. Proverbs, in the Bible, talks about seeking wisdom, and inscribing wisdom on the ‘tablet of your heart’ through memory and practice. The Bhagavad Gita says: ‘It is difficult to curb the restless mind, but it is possible by constant practice and by detachment’.

There is some evidence that CBT works better when its basic ideas and techniques are connected and translated into local language and local culture. Here, for example, is a paper on Islamically modified CBT. Others have developed Christian CBT, and of course mindfulness-CBT now has a strong evidence base, although ironically it is barely known or practiced in India, where Buddhism originated.

Medical humanities scholars can help explore the cultural connections between western psychotherapy and various wisdom traditions around the world, and help to discover the local vernacular for local emotional states.This will help people overcome their suspicion of therapy. Speaking personally, for example, I’ve done workshops on healing wisdom for evangelical Christians, where you can describe the basic ideas of CBT purely using quotes from the Bible and Christian wisdom literature. That is helpful for an audience which has traditionally been wary of psychiatry and psychology, partly because of psychiatry’s long history of hostility towards religion.

At the same time, we should remind ourselves that cultures aren’t static and monolithic. There is no such thing as ‘Indian culture’, for example, there are many Indian cultures, all in flux. A 2013 article in the Indian Journal of Psychiatry calls for the ‘Indianization of psychiatry’ to take account of cultural differences such as the greater emphasis on traditional family structures. Fine – but Indian therapists also tell me of the stress and suffering caused to some Indian women by the traditional understanding that their role is entirely to support their husband and his family. Therapy can help people not just adjust to traditional roles, but also help them evolve into new roles, new identities, a new place in society.

Working with local spiritual healers

A second way that medical humanities researchers can help to bridge the cultural gap between non-western cultures and western psychiatry / psychotherapy is by working with local religious and spiritual leaders, facilitating dialogues of mutual respect to work together.

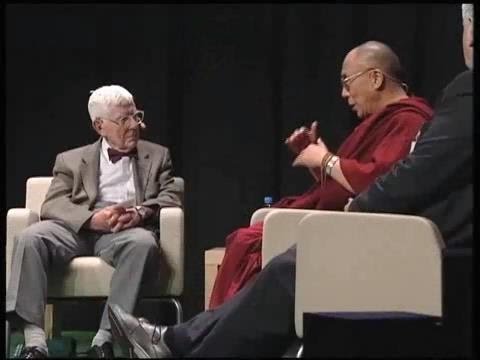

Aaron Beck, one of the inventors of CBT, with the Dalai Lama, who has spoken about the close similarity between CBT and Buddhism’s theories of the emotions

At my university, Queen Mary University of London, a team of psychiatrists are working with local Muslim spiritual healers, to try and improve relationships with a community that has traditionally been very wary of psychiatry. The latest issue of the WHO’s Panorama magazine has an article on psychiatrists working with Kyrgyz spiritual healers. In India, I think it would help to work with local spiritual leaders like Sadhguru, the best-selling yogi who regularly speaks on yoga as a means to mental health. We already know how fruitful the dialogue has been between western psychiatrists and psychologists and the Dalai Lama – it has helped western psychotherapy advance.

Finally, I think technology has a role to play in improving global mental health. Governments are spending far too little on mental health services, and should be encouraged to spend more. But could the WHO or other organizations like the Wellcome Trust help to develop apps, websites and online courses, in local languages and local cultural terms, to disseminate basic therapeutic ideas and techniques? It would not be enough, but it would be something. And it would be cheap.

I’m working with the WHO on a project called the Cultural Contexts of Health. Find out more about it here.