Hetta Howes is writing a PhD at Queen Mary, University of London on the subject of water and religious imagery in medieval devotional texts by and for women. She was one of the contributors to the ‘Vessels of Tears’ event on 7 May 2014, curated by Clare Whistler as part of her residency at the Centre for the History of the Emotions.You can listen to Hetta talking about her work as part of the ‘Stream’ podcast made by Natalie Steed. In the blog post below, Hetta reflects on the emotional and religious meanings of water for women in the middle ages.

Hetta Howes is writing a PhD at Queen Mary, University of London on the subject of water and religious imagery in medieval devotional texts by and for women. She was one of the contributors to the ‘Vessels of Tears’ event on 7 May 2014, curated by Clare Whistler as part of her residency at the Centre for the History of the Emotions.You can listen to Hetta talking about her work as part of the ‘Stream’ podcast made by Natalie Steed. In the blog post below, Hetta reflects on the emotional and religious meanings of water for women in the middle ages.

There is something about water that resists definition. It slips and slides out of our grasp, twisting and turning elusively then pooling into stillness when we least expect it. The initial impulse of Clare Whistler and Charlotte’s Still’s Stream project was an urge to seek out, or return to, a source. Yet on the way to the source they were, inevitably, diverted. Water guided them to elsewhere and held them there, asked them to be still. This, to me, seems to suggest something bigger, almost ineffable. So much of our language reveals a desire to return to a source, to find an origin: ‘let’s go back to the beginning’, ‘where it all began’, ‘this was the catalyst’, ‘this was the moment,’ ‘it was at this point that…’ Yet so often in our search for this beginning, for this origin or source, we are distracted; we take a different path; we find something we didn’t know we were looking for. We believe our impulse is to find a source but perhaps, in actuality, it is something quite different: water seems to be able to describe this feeling where words fail. My own research on water and tears has often felt much like this: I’m constantly pulled in different directions, side-tracked. But today, I’m going to try and give you a brief insight into the relationship between women and water in the middle ages and how tears became, for them, a watery offering, helping them gain greater access to Christ.

I think it’s fair to say that even today there is a strong association between women and water. Sociologists such as Klaus Theweleit and writers like Ann Carson have tracked this relationship. Nevertheless, it was particularly resonant in the later middle ages, hard-wired into medieval medical and theological theories. It was believed at the time that every human body was made up of four humors: yellow bile, black bile, phlegm and blood. Each humor had an elemental counterpart (water, air, earth and fire) and a healthy body was dependent on their balance. Men and women were partly differentiated by their humoral composition: Women were believed to be slightly more watery and therefore more phlegmatic, whereas men were more hot and dry, associated with fire and a slight excess of yellow bile. This excess of water and phlegm in women was viewed with unease and ambiguity. In contrast, the hot and dry nature of men was generally imagined to be a bit of a bonus.

There are a number of explanations for this belief that women were excessively watery but one of the most influential is menstruation. Once a month, women bled and people did not really know why. It was, everyone knew with certainty, something to do with the curse of Eve, a woman’s punishment and her cross to bear – like childbirth. But beyond that no one was absolutely sure (theories were certainly suggested but usually fell very wide of the mark). What has menstrual blood got to do with water? In the middle ages, it was common belief that all bodily fluids were variants of blood, including water. Thus the monthly purging of watery blood perpetuated the association of women with water, and the idea that women’s bodies were disproportionately moist, even leaking. To give a taste of how menstruation, and therefore this excess of water, was viewed let me offer a few examples of medieval folklore on the matter. Menstrual blood could poison men, particularly their voices. It was polluting, even dangerous. Menopausal women who no longer bled were, somewhat ironically, viewed with particular anxiety. All that blood had to go somewhere, and many thought that it travelled up through the body to leak out of the eyeballs. If a woman in such a state looked upon a child then they could poison, even kill them; this was called ‘the evil eye’. These beliefs were not reserved for old wives’ tales. Isidore of Seville, an eminent and well-respected theologian and encyclopaedist of the tenth century, whose texts and ideas were still very much in currency in the later middle ages, wrote: ‘in the presence of menstruating women, crops do not germinate, wine sours, grass dies, trees lose their fruit, and iron rusts.’ The blood didn’t even need to come into physical contacts with these objects to cause their destruction. The women just had to be nearby.

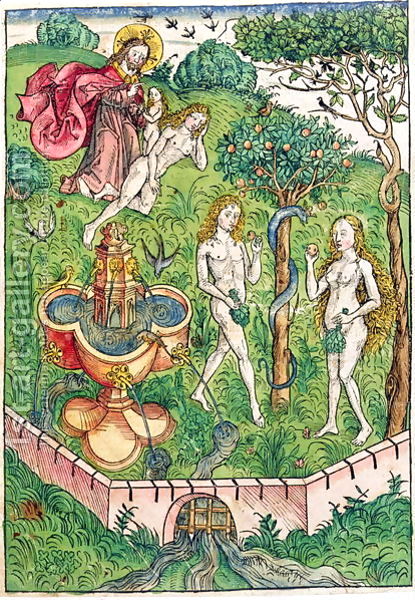

The relationship between women and water was carefully delineated in late medieval medicine, then, but this was not the only factor at play in perpetuating the association. For one thing, women were perceived as changeable and so was water. Water transforms and can cause transformation in other objects; it twists and turns and changes direction; it becomes ice or it boils; in folklore and legends, such as Ovid’s Metamorphoses (which incidentally enjoyed a revival in the twelfth century), water is frequently the site of change. Hermaphroditus enters the water and is bonded forever with his female pursuer, becoming both male and female. Cyane, in her grief, actually dissolves into water. Women, too, were viewed as changeable. In much medieval literature, be it romance or religious, women are portrayed as inconstant or unfaithful. Ever since Eve’s betrayal in the Garden of Eden it had been understood that women found it difficult to remain constant. On a more practical level, women had a lot more to do with water in everyday life than men. They were the stewards of water. It was their job to fetch and carry water and purify it as best they could, their job to cook, clean and prepare food as well as to keep their families healthy. In many countries today, water is still very much part of a woman’s domain in just this way. In the middle ages, the only members of the community who could perform a baptism other than male priests were midwives, usually well-respected women over fifty years of age.

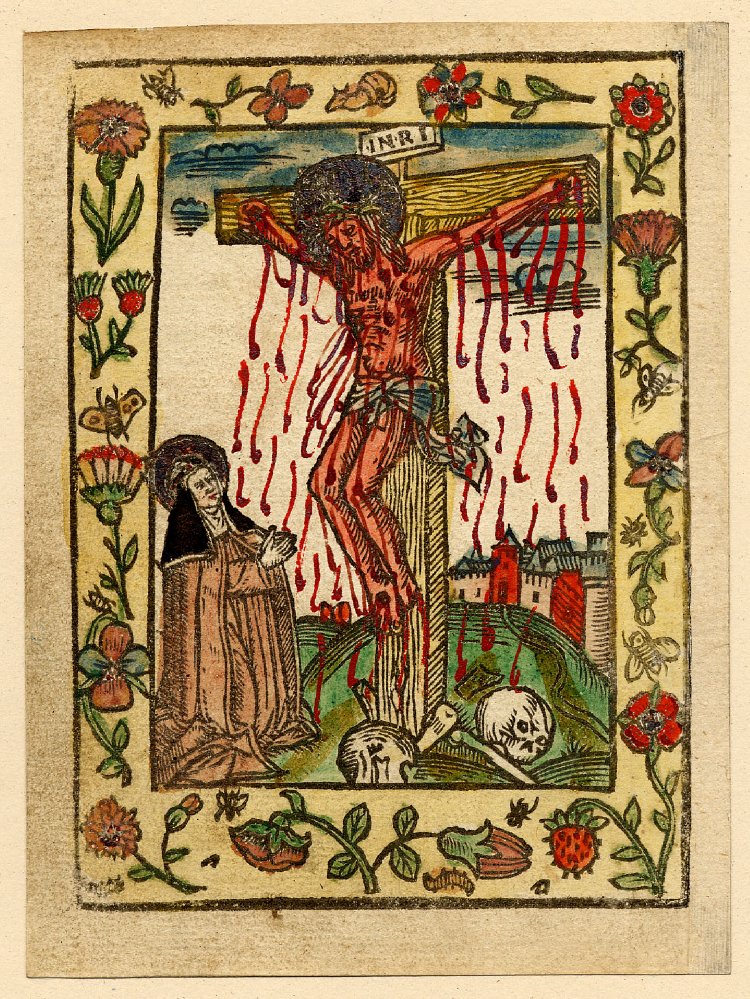

The association between women and water, from the above examples, seems ambiguous at best, negative and disturbing at worst. However, in much medieval literature and religious practice, this association became surprisingly positive in the late middle ages. Both male and female spiritual writers subverted expectations and recast the water-and-women relationship, allowing women to take steps to reclaim it, helping them use it to their own advantage. Before casting some light on this spiritual trend, it is worth reflecting for a moment on the religious practice of imitatio Christi. This practice involves following the example of Christ, even imitating his behaviour, in order to forge a closer connection with him and to promote affective piety. A Christian might fast, to follow Christ’s example in the wilderness, or they might self-flagellate to understood how he felt during the flogging of the Passion. Increasingly in the later middle ages, particularly the fourteenth century, women were beginning to understand that they could perform imitatio Christi simply by reflecting upon their own femininity. Their body was termed leaking, excessively watery, suffering in its incompleteness. Look at any of the evocative medieval art depicting Christ on the cross, with blood and water flowing from a wound in his side, or sweating blood on the Mount of Olives, and another body suffering, leaking and incomplete will be evident. Historians like Caroline Walker Bynum have taught us to see this connection and to understand that women in the middle ages saw it too, used it to forge a deeper and more personal connection with their God. In the concluding section of this paper I want to share some of the findings in my research so far, which seem to deliberately exploit this relationship between water and women, the female flesh and Christ.

One genre of text which I have spent a lot of time with the past two years are Passion narratives or meditations. Passion narratives were sections of spiritual treatises which were often directed at religious women who wanted to enhance their own spiritual experience. They described events from the life and death of Jesus Christ and asked their readers to place themselves at these very scenes. It encouraged them to meditate on these moments, to think about how they would have felt, to imagine how they might have acted and responded as individuals if they had been present. The pains and sufferings of Christ were depicted in excruciating detail to promote affective piety. When reading these texts, specifically those addressed to women, I have noticed that authors frequently turn to water in order to facilitate reader participation, particularly in scenes of the Passion and crucifixion. One particularly important text, in this respect, is St. Aelred of Rievaulx’s letter to his sister, A Rule of Life for a Recluse. This letter, which is really more of a spiritual treatise, was originally written in Latin in the twelfth century but was widely circulated and translated twice into vernacular Middle English, in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, proving that it reached a much wider audience than Aelred’s sister.

Throughout the Passion meditation in this text, which is one of the first of its kind, the female reader is urged to connect with Christ, and participate in scenes of his suffering, via the element of water, particularly tears. She is urged in startlingly imperative language – go to him, run to him, quickly, why are you waiting about? – to lick the dust from his weary feet, to wipe away the defiling spit of sneering bystanders with her tears, to cry with grief as she watches his suffering, to wash his feet with her tears and to use those tears to attract his attention if he seems dismissive of her in these meditations. If Christ tries to move his feet away when the reader is imagining washing them, for example, Aelred guides her to:

[s]tand still, nevertheless, steadfastly and pray meekly. Set your eyes on him all spattered with tears, and with deep sighing and piteous crying catch from him what you covet. Wrestle earnestly with your God as Jacob did, for faithfully he will be glad that you overcame him. […] abide there still, and greedily cry to him without ceasing.

Tears, in this way, become a calling card for the female reader, a way of gaining Christ’s attention and his pity. Tears, if they stem from purity of intent, are the one thing Christ cannot turn his back on or ignore – – even if the weeper is a sinner. Throughout the Passion meditation water becomes a peculiarly intimate element of connection between reader and Christ; Mary Magdalene might wash Christ’s feet with ointment, but in these meditations the female reader is allowed to imagine doing so with her own tears. The relationship between women and water is here turned on its head and expressed positively, even triumphantly. The text still functions within the limits of a misogynistic framework, in which a watery association is imposed upon women by male thinkers. Nevertheless, it twists and turns within this framework in order to reach a new understanding of the women/water connection.

It is difficult to come to many firm conclusions when speaking, writing, or thinking about water, which is, by nature, a slippery element and a difficult one to pin down. Nevertheless, I’ve tried in this paper to give a snapshot of a particular use of water and tears in a particular time period and in a particular context. Women in these texts made their watery offerings to Christ in the form of tears and this paper has been my own watery offering to you.

Read more about ‘Weather, tears, and waterways’.

Read about and listen to all of the related podcasts.