Dr Thomas Dixon is Director of the Queen Mary Centre for the History of the Emotions. Here he reflects on the meanings of love, as discussed at a recent one-day conference inspired by the writings of Constance Maynard, and hosted by the Centre.

According to Saint Augustine of Hippo, in The City of God, all the passions of the soul are manifestations of a single principle, which he referred to as ‘love’ (amor) or ‘will’ (voluntas). Each of us, on this view, has either a good, divine love or a bad, worldly love, driving all our feelings and actions.

This week the Queen Mary Centre for the History of the Emotions hosted a one-day event to mark the completion of the digitisation of the autobiographical writings of Constance Maynard (the downloads take some minutes each, but it is worth the wait as the materials are extraordinary). The day was entitled ‘Love, Desire, and Melancholy: Inspired by the Writings of Constance Maynard‘ and was organised by a committee chaired by Lorraine Screene, who is responsible for the Queen Mary archives.

The dominant theme of the day was undoubtedly love: sexual love, romantic love, religious love; love between women, love of God, love of humanity; love reaching across social, physical, and metaphysical divides. And it was clear, from talks given by the first keynote, Pauline Phipps, and by several others during the day, that Maynard’s own view of love had much in common with that of St Augustine.

Maynard’s autobiographical writings (the ‘Green Book’ daily diaries, and the much later unpublished Autobiography which she constructed from them) narrate a struggle between worldly and divine passions, which were played out especially in her relationships with other women. In 1882, Maynard became the first Mistress of Westfield College: an institution designed to prepare Christian young women to take BA degrees from the University of London. Westfield was one of the institutional ancestors of Queen Mary. Maynard held this post for thirty-one years, and during that time had several intense loving relationships with the young women under her authority, which had both physical and spiritual dimensions. Before her death, Maynard’s instruction to her biographer, Catherine Firth, was ‘don’t forget the love’.

Historians struggle to reconstitute and understand the emotional lives of the people they study. Indeed, most of us struggle to understand our own emotions, let alone those of long-dead individuals who lived and moved in radically different cultures. So what can we say about love lives of the past? Other speakers at the conference provided further fascinating examples. Helena Whitbread has spent nearly thirty years working on the nineteenth-century diaries of Anne Lister, which were partly written in a secret cipher, and often concerned Lister’s loves for other women. Whitbread’s talk outlined the rationalist and religious, as well as romantic motivations behind Lister’s voluminous autobiographical writings. At one moment of despair over an unrequited passion in 1832, Lister wrote in her diary, ‘Flow on, my miserable, foolish tears.’

Muriel Lester in 1938.

Seth Koven is currently working on a book entitled The Match Girl and the Heiress about the loving relationship between an East-End factory worker, Nellie Dowell, and a well-to-do pacifist, feminist, humanitarian, and friend of Mahatma Gandhi, Muriel Lester. His keynote address introduced some of the extraordinary sources from which he is working, especially the arrestingly direct, intense, ungrammatical, and yet fluent letters written over many years from Nellie to her beloved Muriel. Koven brilliantly compared these letters with some of the experimental modernist writings of Gertrude Stein.

Nellie and Muriel were united by their commitment to a particular devotional vision described by Koven as a ‘God is love’ theology, as well as by their ‘epistolary erotics’. ‘In loving one another’, he said, ‘they sought to remake the world’. They did this by their work founding Kingsley Hall, in 1915, a Christian revolutionary people’s hall located in Bow, in the East End of London, as a centre for social reform and brotherly love.

The historian, then, sits down with these handwritten and printed words, diaries and letters, memoirs and autobiographies, and tries to imagine the emotions of the past, to feel forgotten feelings afresh. And, judging by the many shared aims and concerns of the speakers at this conference, this itself is a collaborative endeavour, fuelled by a desire faithfully and carefully to reconstitute the minds of the past, while offering inspiration and liberation to minds in the present. Carol Mavor emphasised the role of creativity and imagination in trying to revivify past feelings; her presentation reflected on the layers of homoerotic and incestuous imagery detectable in the ‘Paul and Virginia’ photographs made by Julia Margaret Cameron.

In all of this, two themes that are close to my own heart emerged: the need to pay close attention to the language and categories of historical actors (which was emphasised by Laura Doan and others); and the importance of understanding theological and devotional terms and genres when trying to comprehend the lives of Victorian and post-Victorian subjects. Angharad Eyre’s analysis of the place of love, emotion, and tears in the literatures of evangelical conversion, and Sue Morgan’s account of Maud Royden’s 1921 book Sex and Common Sense, her campaigns against ‘anti-somatic theology’, and her own unusual love life, both illustrated the complex but reinforcing relationships between theological and secular forms of love.

In thinking about the meaning of ‘love’, and how love has been made and remade in the past, the historian needs to keep all these complexities in mind. And my parting thought from the conference this week, as an historian of emotions, was that ‘love’ is not best thought of as an emotion at all. Perhaps Saint Augustine’s approach is better: to think of ‘love’ as an almost unknowable, underlying substance, out of which particular passions, feelings, emotions and experiences might arise.

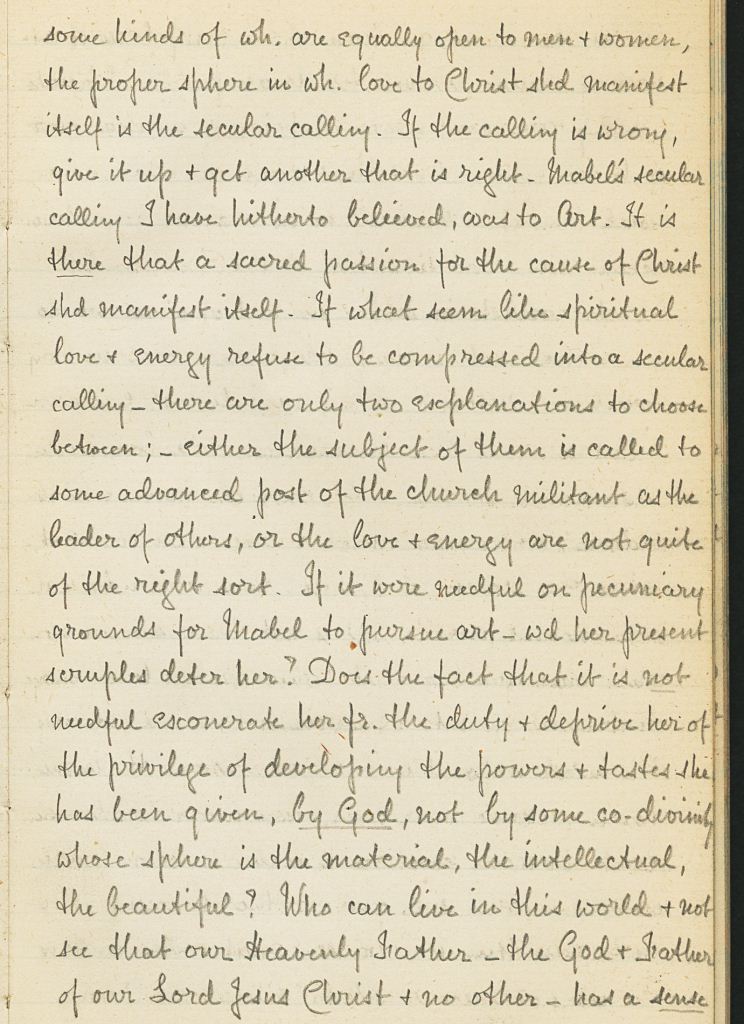

Constance Maynard, in the page from her ‘Green Book’ shown below, written in December 1881, asks whether a ‘spiritual love and energy’ directed towards Christ can find its expression in a secular vocation. The passage discusses a student, Mabel, and the ‘powers and tastes’ she has been given by God. The historian of emotions, then, will need to ask what Maynard meant by ‘spiritual’, ‘energy’, ‘power’ and ‘taste’, as well as ‘love’, and how these terms functioned, when used in particular times and places, in producing and interpreting feelings in herself and others.

Love is made in many ways, all of them at some level linguistic. The historian needs to listen carefully to the languages and dialects of the heart, through which love is called forth, expressed, made, and reinterpreted. Writing in her autobiography towards the end of her life, in her late seventies, Constance Maynard wrote that she supposed that psychoanalysts would say of her feelings that they revealed as ‘thwarted sex instinct’. Maynard rejected this language, preferring to write of the ‘hunger’ she had felt, which needed satisfying. That was clearly a spiritual need – a hungering and thirsting after righteousness – as much as a psychological one. To the end she feared that her great fault had been to prefer human to heavenly love.

One passage of Maynard’s writing, quoted by Pauline Phipps in her lecture, has particularly stayed with me. It encapsulates the intensity and complexity of Constance Maynard’s experiences of love, desire, and melancholy. This was written at the end of her life, looking back at a relationship with the twenty-five year old Marion Wakefield, thirty years earlier:

I feared that I might love Marion! The colours grew more brilliant as I thought of it. Meanwhile Christ stood beside me, offering me white, pure white. I must choose white, and I will. I dread love … Am I a Minotaur that I must eat a maiden’s heart?

Pingback: Review of Constance Maynard conference on the History of the Emotions Blog! « A Woman's Thoughts About Women and Faith in the 19th Century

A thought provoking and stimulating day. The challenges of interpreting emotion, love and desire through and in the language of historical sources is problematical but as the speakers demonstrated, fascinating and exciting. Digitising archives certainly makes it easier as does organising a conference with internationally acclaimed speakers and inviting researchers and PhD candidates to attend.

Pingback: Evangelical Emotions and Constance Maynard | The History of Emotions Blog