I was teaching an undergraduate seminar this afternoon on Oscar Wilde and Catholicism. We discussed Wilde’s statement that ‘Those who see any difference between soul and body have neither.’ Wilde’s fascination with the sensual materiality of Catholic rituals, especially the mass, is evident in much of his writing. There is a description in The Picture of Dorian Gray of the sounds, smells and sensations involved in kneeling on a cold marble floor, watching a priest in his stiff vestments raising the consecrated host in a bejewelled monstrance, while the altar boys, dressed in lace and scarlet, swing censers that fill the air with the smell of fuming incense. Earlier in the book Lord Henry has told Dorian Gray that ‘Nothing can cure the soul but the senses, just as nothing can cure the senses but the soul.’

One of the fascinations of the history of the emotions is how it examines the relationship between body and soul as it has been reconstituted in different periods. A lot of the most interesting recent work in this field has shown how emotions are acutely sensitive to place – both to geographical locations with associated national stereotypes, and to physical spaces such as courtrooms, classrooms, clinics, chapels, or churches.

Two recent talks by visiting PhD students at the QMUL Centre for the History of the Emotions reinforced this point in interesting ways earlier this month. At one of our regular lunchtime seminars, Alina Danet, an historical sociologist, spoke about organ transplants in Spain and the construction of emotional responses, while Juan M. Zaragoza used examples relating to terminal illness and the history of medicine to argue for the importance of material culture to the production of emotions.

Alina’s research explores the role of the Spanish press, since the early twentieth century, in creating a particular emotional climate in relation to the possibility, and subsequently the actuality, of organ transplantation (the first kidney transplant in Spain was in 1965, the first heart transplant there in 1968). Through national newspaper reports, Spaniards were encouraged to feel a range of emotions: empathy with those in need of transplants, national pride in their country’s scientific and medical advances, anxiety about their own health, shame at their failure to offer to donate their organs, or fear of the medical, moral and even metaphysical implications of organ transplantation.

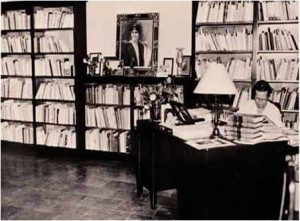

Juan’s project has also involved researching the medical and emotional history of modern Spain. In his case, the focus is on terminally ill patients and their mental lives. He uses the example of the Spanish poet Juan Ramón and his wife Zenobia. Ramón had been diagnosed with neurasthenia and Zenobia with uterine cancer. During this difficult period Zenobia founded a new room at Puerto Rico University – a reading room and study for her fragile husband, and others, to use. Zenobia had worked as an interior designer and set to work choosing the tables, chairs, bookshelves, lamps, sculptures and paintings which would create an emotional atmosphere conducive to health. As Juan put it in his talk, places and material objects are integral to the affective life of the past: the historian cannot disentangle ‘the emotions and the stuff ‘.

Lord Henry’s revelation to Dorian Gray that the soul can be cured only through the senses seems particular apt in the case of Juan Ramón and Zenboia’s curative room in Puerto Rico. The awareness of the power of rooms, their contents, and decoration was a recurring theme in Wilde’s work. During his lecture tour of America in 1882, Wilde was reported to have said, in the course of a lecture on the importance of house decoration: ‘Why, I have seen wallpaper which must lead a boy brought up under its influence to a career of crime; you should not have such incentives to sin lying about your drawing-rooms’.

An ’emotional climate’ or ’emotional atmosphere’ of the kind Alina and Juan both discussed in their papers can sound intangible, but historical research can demonstrate the agency of physical stuff, including even wallpaper, in producing such phenomena.

Thomas Dixon

Pingback: Sensibility and history: The importance of Lucien Febvre | The History of Emotions Blog

Pingback: Kleenex tissues and the meaning of ‘epiphylogenesis’ | The History of Emotions Blog

Pingback: What is the history of emotions? Part III | The History of Emotions Blog