Angharad Eyre is currently working on a PhD thesis on the impact of the female missionary on religious women and their writing through the nineteenth century. She was one of the speakers at the one-day conference on Constance Maynard hosted by the Centre for the History of the Emotion in November 2012. Here she writes about Maynard and the emotions involved in the Evangelical conversion process.

Constance Maynard’s life was one of love and passion, as has been noted in a previous post on this blog. And it was the interpretation of that passion as part of a religious experience that enabled Maynard to understand her relationships with young women as part of her religious mission and identity.

In my research into female missionaries in the nineteenth century, and how they experienced love for God, their missionary husbands and their native converts, I have encountered Evangelical religion as something that made great demands of women. The height of emotion required to demonstrate true conversion and piety was difficult for many young women to achieve. For example, Harriet Newell’s biography (published 1816 and reprinted through the century) quotes her journal in which she cursed her ‘cold, stupid heart’ for failing to feel enough in prayer and causing her to hesitate in her decision to go out to India as a missionary.

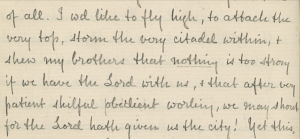

Constance Maynard seemed to have no such trouble feeling passionate about her religious mission. In the same way that Wesleyan female missionaries (in published letters) expressed military fervour for their mission – it was a ‘campaign’ to ‘attack’ the strongholds of idolatry – so Maynard in 1881 (in one of the diaries recently made available online) expressed her mission to convert the daughters of the upper-middle class with passionate zeal:

I would like to fly high, to attack the very top, storm the very citadel within, to shew my brothers that nothing is too strong if we have the Lord with us, and that after very patient, skilful obedient working, we may shout for the Lord hath given us the city!

Another aspect of Evangelical culture that encouraged strong emotion was its encouragement to of the use of love and friendship to convert other women. Religious literature for children, especially that written by Martha Sherwood (1775-1851), paints vivid pictures of the expression of religious love within conversion narratives. For example, in Caroline Mordaunt (1835), the eponymous governess becomes converted by her young charge, Emily, a preternaturally holy child. However, the relationship is depicted in such a way that suggests a passionate affair or infatuation. Caroline and Emily are often in each others’ arms and there is secret hand-holding at the dinner table. Emily’s tears are often described as ‘violent’, and Caroline becomes ‘possessed’ by the idea of Emily, as well as by her beliefs. She notes that the child’s claiming of her ‘to love me’ left her disordered, unable even to read, the child had so ‘thrown [her] mind’.

This relationship is shown to be the result of religious conversion. Emily expresses an idea that there is a link between loving a woman and growing in faith when she says ‘I shall have you to love me and read the Bible to me’, linking these two activities. Emily’s status as a child-saint, makes more apparent the idea that the converting female missionary is a vessel for God to work through; the passion instilled by the child in Caroline is given greater solemnity and status as it is love for God, elicited by and bestowed through his vessel. Ultimately, the relationship, combined with the conversion, leads her to take up a missionary role with all her subsequent students.

It is this sort of relationship, I think, that Maynard aspired to with her students when she was principal of Westfield. In one of her relationships – with Margaret Brooke in the first few terms of Westfield – she appears to have succeeded. Even in her oftentimes remorseful diary of the Westfield years, Maynard remembers this relationship with pleasure as ‘restrained and lovely’.

When reading Maynard’s diaries of this first relationship and those first few months of Westfield, I was struck by the heady mixture of religion and love described. It is no coincidence that Maynard falls in love with Brooke around the same time of the first successful prayer meeting at Westfield. She describes this event as transforming her relationship with her students:

My students are more good, more interesting, more loveable than I could have thought […] the Spirit of God seemed near. For the first time I kissed their dear faces in succession […] Katie stayed a minute […] she seemed hardly to know how to speak of it.

The kisses she distributes here are the direct result of a shared religious experience – an experience so intense that there are no words to describe it as it approaches a sort of godly excess.

Most of Maynard’s intimate encounters with Brooke take place after similar experiences of religious enthusiasm. Brooke visits Maynard’s room after this very prayer meeting. A few months later, a similar result is achieved through Maynard taking her students to a Salvation Army meeting:

The stirring singing and the few searching words from Mr Booth, touched my beautiful little Margaret as I stood with my arm around her, and on parting with her she whispered, ‘Oh come, just for Goodnight to my room!’

When Maynard describes what happens between the two of them she clearly recognises the ‘human feeling’, the strong ‘physical power’ that Brooke has over her. However, she continually defends her actions and feelings through the language of her religion. If ever she doubts the moral rectitude of the relationship, she reminds herself that this love is working to convert Brooke. She writes in her diary: ‘It is leading her to closer to the Lord, it really is, and surely this should be the test.’

Overall, I hope this attention to Maynard’s experiences, through her autobiographical writings, can add to our understanding of female friendships and relationships as they could have been understood by religious women in the nineteenth century. While Maynard experienced strong female friendships at Girton, it was when these sorts of relationships were combined with the strong emotions of Evangelical missionary religion at Westfield that she could really understand and enjoy her experiences with other women.