Eleanor Betts is a PhD candidate at the Queen Mary Centre for the History of the Emotions, researching the history of children who killed in Victorian Britain.

In 1892 a sixteen-year-old boy named John Wise joined his friends on an excursion to Weymouth. On reaching the chosen destination, a stone’s throw from Portland Prison positioned high on a rocky peak, the boy spun round and pushed Lawrence Salter off the cliff. At the coroner’s inquest into the boy’s death Wise explained his reason for committing murder. He simply said, ‘I did it to be hanged.’

When we are told that a person has committed murder we are quick to imagine reasons and motives in order to understand the crime. Perhaps the murder was committed out of revenge; we see that daily on television and in cinemas. Perhaps jealousy was the main cause, or maybe the killer was mad? A similar need to explain away violent crime could also be seen in Victorian England. The Manchester Times was quick to rationalise the murder committed by Wise, ‘the boy is either a shocking example of human depravity or he is insane.’ The article concluded that, ‘a boy murderer is such an awful creature that one is glad to be able to attribute the Weymouth tragedy to mental aberration.’

But how do killers rationalise their own crimes? What language do they use to understand and explain why they committed murder?

Much to my surprise I uncovered a number of written confessions by children who were charged with murder in nineteenth-century England. These sources were unexpected on a number of grounds, not least because every historian of childhood knows how rare it is to find testimonies actually written by a child, but also because the confessions were written in pencil on very flimsy paper. Quite how they survived I do not know, but thank goodness they did. I now have in my hand word-for-word explanations written by children who committed murder. So why did they do it?

From the few written confessions I have found there are a number of reasons children used to explain their crimes; employing the language of insanity, of passion, and of provocation. But perhaps the first explanation provided was no explanation at all, but rather a denial.

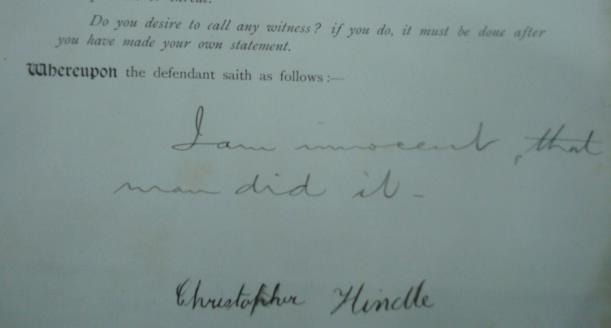

It was widely recognised in nineteenth-century England that children had a natural propensity to lie. Moral and educational literature designed for children promoted the motto that, ‘honesty is the best policy’ (E. Buttery, Advice to Boys, With a Poem Entitled Come to God (London, 1887), p. 2) and numerous works associated with the Child Study Movement of the 1890s recognised lying to be a natural characteristic of childhood. The fact that children lied in their confessions is not surprising, criminals deny their guilt all the time. It is the detail in the lies and the narratives that the children drew upon to validate their excuses that are notable. For example, in 1896 fifteen-year-old apprentice Christopher Hindle, charged with murdering the wife of his master, wrote as his confession, ‘I am innocent, that man did it.’ He contrived a story where a strange, ragged man broke into the house to commit the murder, but not before Hindle tried to stop him receiving wounds for his bravery. The boy was careful to use the knife he had killed the lady with to cut his own arm, leaving behind a trail of blood that made him look as innocent as he claimed. So why invent the ragged man? This is a story that appears in numerous confessions by children charged with murder. These children were drawing on the popular image of the ‘murderer’ that existed in the Victorian imagination; murderers were adult, male, ragged, and strangers to the victim. It was this image that lay behind the numerous press representation of Jack the Ripper in 1888.

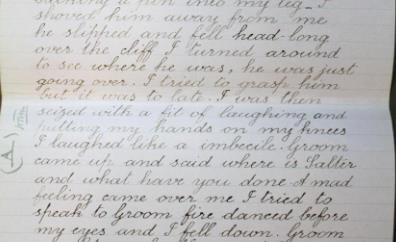

The explanations provided in the written confessions of children who killed can therefore tell us a lot about the popular notions surrounding murder that existed in nineteenth-century England. In addition to the wandering, ragged, male monster, murderers were also assumed to be insane. Their monstrosity did not necessarily make them inhuman, it made them abnormal. As can be seen in the confession by John Wise, the boy drew heavily on narratives of insanity to understand his crime and to explain his actions to the coroner’s jury. He wrote, ‘I tried to grasp him but it was too late. I was then seized with a fit of laughing and putting my hands on my knees I laughed like an imbecile. Groom came up and said where is Salter and what have you done. A mad feeling came over me I tried to speak to Groom fire danced before my eyes and I fell down.’ Whether Wise knew it or not he employed notions of imbecility and fiery passion to explain his reasoning for pushing the boy off the cliff, if there was any reasoning involved in the crime at all. The jury were convinced by the confession and Wise was found to be guilty of the murder but insane. He spent the early years of his adult life in Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum.

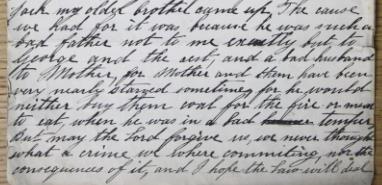

Another explanation for murder that existed in the Victorian imagination was provocation. When two brothers were found guilty of murdering their father in 1890 the Victorian public flocked to their defence. Richard Davies, the older brother, explained in his confession that they committed the murder to save their mother and younger siblings from their abusive father. He wrote, ‘the cause we had for it was because he was such a bad father not to me exactly but to George and the rest, and a bad husband to mother, for mother and them have been very nearly starved sometimes, for he would neither but them coal for the fire or meat to eat when he was in a foul temper.’ The abuse suffered by the Davies family at the hands of the victim reduced the seriousness and monstrosity of the crime in the eyes of the Victorian public. They flocked to the boy’s defence, local and national newspapers filled with appeals to the Home Secretary to show mercy. The same compassion was not to be found in the Law. Although certain types of provocation were permissible in court, reducing a charge of murder to one of manslaughter, the Judge ruled that abuse was not one of them. In his summary to the jury he maintained that, ‘the counsel’s claims that the father drove the boys to it was no excuse for a crime such a murder’, and the two boys were sentenced to death. Richard was hanged.

So why have I shared these sources with you? Partly because I was so excited to find them that I thought they needed to be shared. It is not every day an historian of childhood finds themselves holding a piece of paper containing the scribbled scrawl of a child, let alone a child who was sitting in a condemned cell when he wrote it. But these written confessions are also interesting because they show how the Victorian public approached murder, how they sought to explain and understand why one human being could kill another. Children understand the world through what they see and hear; they parrot the adults around them. In analysing how children found the words to explain why they committed murder we are able to understand the place of murder in the Victorian popular imagination.

Follow Eleanor on Twitter: @BettsEleanor

Fascinating blog Eleanor and great research topic. I’m intrigued to know whether Victorians were more sympathetic to child murderers than we have been in recent times. I’m also intrigued to hear about how you came across these confessions.

Helen

These are fascinating sources! Two things occur to me from reading your piece: how are you identifying these confessions as written by the child in question and not, for example, taken down by an adult present at the questioning? And, second, looking at the Davies case you discuss last, it is interesting to wonder if the public would have flocked around two girls who had killed an abusive father.

Fascinating reading – the result of some really hard core research. I find the period, and the difference between children then and now, fascinating. Please don’t waste this wonderful research – a book please! Put me down as the first buyer…

I’m curious to know why you concluded that the boy who said a ragged man entered the house and killed his boss’s wife was lying. Is it inconceivable that a ragged man attacked the wife? Or was there a further confession after that initial assertion of innocence?

I have plans to write a book on the Coates Murder in Accrington

re: Christopher Hindle…

Hi

I read with great interest your article on Christopher Hindle ( I have just bought a shop on the same street)

where this murder was committed… I have all the local press cuttings: I was wonder if you had any more information on him: I was really interested to see him confession ( I also have more information) that maybe he did not kill Sarah Coates: could you please contact me many thanks Evonne:

Pingback: Love, Pain, Ecstasy, and Murder: A Christmas Present | The History of Emotions Blog