This guest post by Mark Bradley is part of Disgust Week, in which a group of scholars from a range of disciplines explore different aspects of disgust.

Mark Bradley is Associate Professor of Ancient History and Associate Pro-Vice-Chancellor for Education at the University of Nottingham. He is author of Colour and Meaning in Ancient Rome (2009) and Editor of Papers of the British School at Rome. Together with Shane Butler (Johns Hopkins), he is co-editor of a series of volumes on ‘The Senses in Antiquity’, for which he has contributed a volume on Smell and the Ancient Senses (2015), and he is currently writing a monograph on Foul Bodies in Ancient Rome.

‘Papylus, your nose and your dong are both so long that when your dong grows, your nose knows.’ This short comic epigram by the Roman poet Martial caricatures the obscene Papylus by imagining him as a grotesque figure with a giant nose stretching out to meet his stinking phallus. But Martial’s Papylus was more than just a grotesque spectacle: the nose that mirrored his phallus drank up its own foul odours, conjuring up a host of associations with bestial stench, sexual obscenity and self-indulgent animal sniffing. Martial keeps Papylus’ foul body at a safe distance: the poet knows he stinks, and understands what that means, and his barbed satire warns his audience not to get too close.

![Figure 1: Pan copulating with a goat. From the Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum. Museo Archeologico di Napoli (inv. 27709). Photo: author.]](https://emotionsblog.history.qmul.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Figure-1-1024x683.jpg)

Figure 1: Pan copulating with a goat. From the Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum. Museo Archeologico di Napoli (inv. 27709). Photo: author

For ancient Greeks and Romans, just as it is for us, disgust was the most visceral of human emotions. Ancient bile was triggered by fear, anxiety, hatred and aversion, and it bubbled up in every area of classical antiquity. And it often manifested itself through the lower senses – smell, taste and touch – experiences that lent themselves less to rational thought and more to basic animal instincts: things that stank, tasted vile or felt funny delivered immediate, tangible warning signs – the moist skin of old women caked in repulsive cosmetic concoctions was a particular favourite of Roman imperial satire, for example, as was the body odour of sexual deviants like Papylus. Ancients also used their eyes and ears to diagnose bodies or matter that did not conform to the expectations of society: complexions, cosmetics and clothing associated with bodies at the margins of civilisation; people who were too fat or thin, tall or short, or who had bits missing or sticking out where they should be; or the shrill voice of eunuchs – all alarm bells for Greco-Roman society, which had developed sophisticated models around beauty and ideal bodies that occupied the perfect, harmonious mean. From the ghoulish and ghastly figures of ancient myth to sexual perverts, unwanted immigrants and deviant emperors, examples of aversion to unwanted, unwashed and unsavoury bodies were legion in classical antiquity, an extensive corpus of evidence that allows us to probe the very foundations of ancient prejudice and the classical body image.

But, as the anthropologist Mary Douglas has shown us, disgust (just like beauty) is far from being a straightforward human universal. Excrement repulses us most of the time, but not necessarily when it is manure on a crop-field; Romans knew that urine smelled, but wouldn’t turn their noses up at it when it was used as a detergent on their clothes (conveniently re-named as lotium, ‘washing-up liquid’), and they had a thing for that rotten fish-paste they called garum, and the stinking shellfish-dye that coloured the clothes of senators, priests and emperors purple. So even what we think of as very basic responses to foul things could be recalibrated and re-learned: dirt is only dirt, foul bodies are only foul bodies, if they’re at odds with a notion of order or civilisation – if they’re out of place.

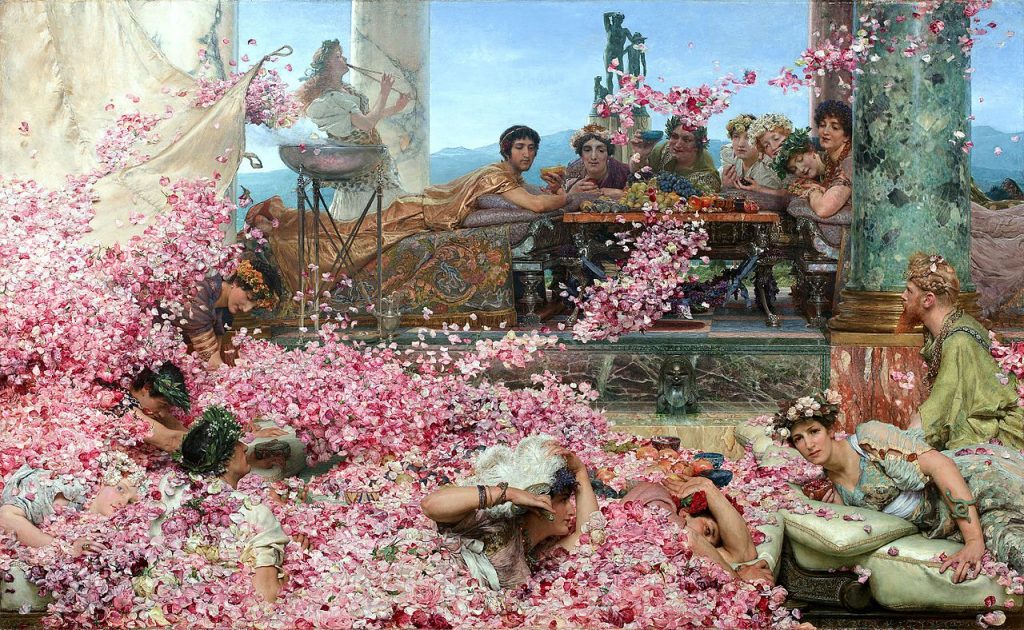

Figure 2: Lawrence Alma-Tadema, ‘The roses of Heliogabalus’ (1888). Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Unsurprisingly, antiquity’s rulers were subject to particular scrutiny, their bodies often probed and dissected in extraordinary detail: in their skin, flesh and bones, the usual story went, lay the key to their character and the regimes over which they were in charge. The stock descriptions of personal appearance in each of Suetonius’ lives of the emperors have been shown to be influenced by prevailing physiognomic doctrine, where bodily defects functioned as telltale signs of imperfections in the emperor’s character and personality: Caligula’s pallor and thin limbs pointed to the fragility of his mental state and leadership, while Vitellius’ obesity underpinned the greed that characterised his regime. Smell also diagnosed foul emperors: the deceptive effeminate use of perfumes and scents by depraved emperors like Caligula, Nero or Elagabalus; the destructive, flatulent Claudius pictured defecating himself as he died; or Maximinus Thrax, who drank so much wine and ate so much meat that he literally sweated buckets, which he would then exhibit by the pint.

This idea of innate foulness exuding from the emperor’s body is most vividly recounted in Lactantius’ description of the death of Galerius, persecutor of Christians, in AD 311, struck down by a terminal disease that started out as a malign cancer on his genitals, which spread around his body despite repeated surgery, eating away at his entrails and dissolving his buttocks in decay. Lactantius revels in his extended account of the gruesome disease:

As the marrow was assaulted, the infection pushed on inwards and seized his internal organs; worms were spawned inside him. The smell spread not only through the palace, but pervaded the whole city. No wonder, since now the tubes for his urine and his excrement were now melted together. He was consumed by worms and his body was dissolved into a state of rot amid intolerable pain.

[quoting Vergil’s Aeneid on the death of Laocoon:] “At the same time he raised terrible cries to the stars, like the bellowing of a bull when he flees the altar wounded”.

Meats cooked and warm were set near his putrefying buttocks, so that the heat could draw out the little worms: when these were broken up, an innumerable swarm of these creatures squirmed out, and the very disaster that had befallen his rotting flesh was fertile in generating a far greater quantity of them.

Lactantius’ gruesome description of Galerius’ illness was part of an indulgent and highly creative exercise in aligning pagan persecution of Christian belief with divine retribution and a graphic assault on the senses: the emperor’s body visibly wasted away, his cries of pain were the stuff of legend, the infection takes hold of his innards, worms eat him up, and the stench of his rotting body filled the entire city. Immediately following this passage, Lactantius imagines Galerius finally giving way and accepting God, and his horrific experience is imagined as the catalyst for Galerius’ Edict of Toleration toward the Christians, which was posted at Nicomedia in 30 April 311, shortly before the emperor finally succumbed to his illness. The rot attacking the state was represented most visibly, tangibly and redolently by the pagan emperor’s rotting body. In Lactantius’ account, the sensations it produced were far more than creative ecphrasis: they functioned as both measure and warning of a regime that required cleansing, correcting and re-ordering.

Deviant bodies, then, were the by-products of a social, political and moral dialogue. Bodies that didn’t fit were usually symptomatic of bigger problems within the state, whether that was sexual promiscuity, social anarchy or corrupt political regimes. And this corporeal deviance was diagnosed most prominently and explicitly through careful, keen use of the senses – through colour, smell, sound, even touch and taste. A fragment of one of Varro’s Menippean Satires, comparing the city of Rome to the human body, describes the senses as the city gates, portals that monitored the relationship between the inside and the outside, that kept an eye, ear and nose on the outside world. Sometimes, as we saw with Galerius, the senses worked in tandem, where lucid and articulate perception of bodies at the margins allows for the educated elite Roman a level of sensory enlightenment: keen eyes, ears and noses told you who to look out for, who to stay away from, and how to learn from others’ mistakes.

Contact mark.bradley@nottingham.ac.uk