Dr Eleanor Betts recently completed her PhD in the School of History at Queen Mary University of London, researching Victorian responses to children who killed. Eleanor continues to work with the Centre for the History of the Emotions and is currently employed as an historical consultant and researcher by the National Trust and the Science Museum. You can follow her on Twitter @BettsEleanor. Below she reviews the new book by Kate Summerscale.

Dr Eleanor Betts recently completed her PhD in the School of History at Queen Mary University of London, researching Victorian responses to children who killed. Eleanor continues to work with the Centre for the History of the Emotions and is currently employed as an historical consultant and researcher by the National Trust and the Science Museum. You can follow her on Twitter @BettsEleanor. Below she reviews the new book by Kate Summerscale.

SPOILER ALERT: If you don’t want to know what happened to the boy murderer in Kate Summerscale’s book then you should read the book before you read this review!

The Wicked Boy: The Mystery of a Victorian Child Murderer, Kate Summerscale (London: Bloomsbury, 2016).

The Wicked Boy, Kate Summerscale’s latest exploration of Victorian murder and police detection, focuses on the crime committed by thirteen-year-old Robert Allen Coombes. In the summer of 1895 the body of a woman was discovered at 35 Cave Road in Plaistow, east London. Ten days previously Mrs Emily Coombes had been stabbed multiple times in the chest as she slept, the murder weapon discarded on the bed just inches from her corpse. Her two sons continued to live in the house knowing full well that the body of their mother lay decomposing in the upstairs bedroom. Their father was away at sea and they told neighbours that their mother was visiting family in Liverpool. A milkman, disturbed by a strange smell emanating from the Coombes family home and concerned by the number of flies buzzing around the front upstairs window, alerted the boys’ aunt. She barged her way into the house, marched upstairs and found the body of her sister-in-law. Robert then admitted to her that he stabbed his mother to death because she had unfairly scolded his younger brother. He was arrested, sent to trial and found guilty of wilful murder.

The Wicked Boy, Kate Summerscale’s latest exploration of Victorian murder and police detection, focuses on the crime committed by thirteen-year-old Robert Allen Coombes. In the summer of 1895 the body of a woman was discovered at 35 Cave Road in Plaistow, east London. Ten days previously Mrs Emily Coombes had been stabbed multiple times in the chest as she slept, the murder weapon discarded on the bed just inches from her corpse. Her two sons continued to live in the house knowing full well that the body of their mother lay decomposing in the upstairs bedroom. Their father was away at sea and they told neighbours that their mother was visiting family in Liverpool. A milkman, disturbed by a strange smell emanating from the Coombes family home and concerned by the number of flies buzzing around the front upstairs window, alerted the boys’ aunt. She barged her way into the house, marched upstairs and found the body of her sister-in-law. Robert then admitted to her that he stabbed his mother to death because she had unfairly scolded his younger brother. He was arrested, sent to trial and found guilty of wilful murder.

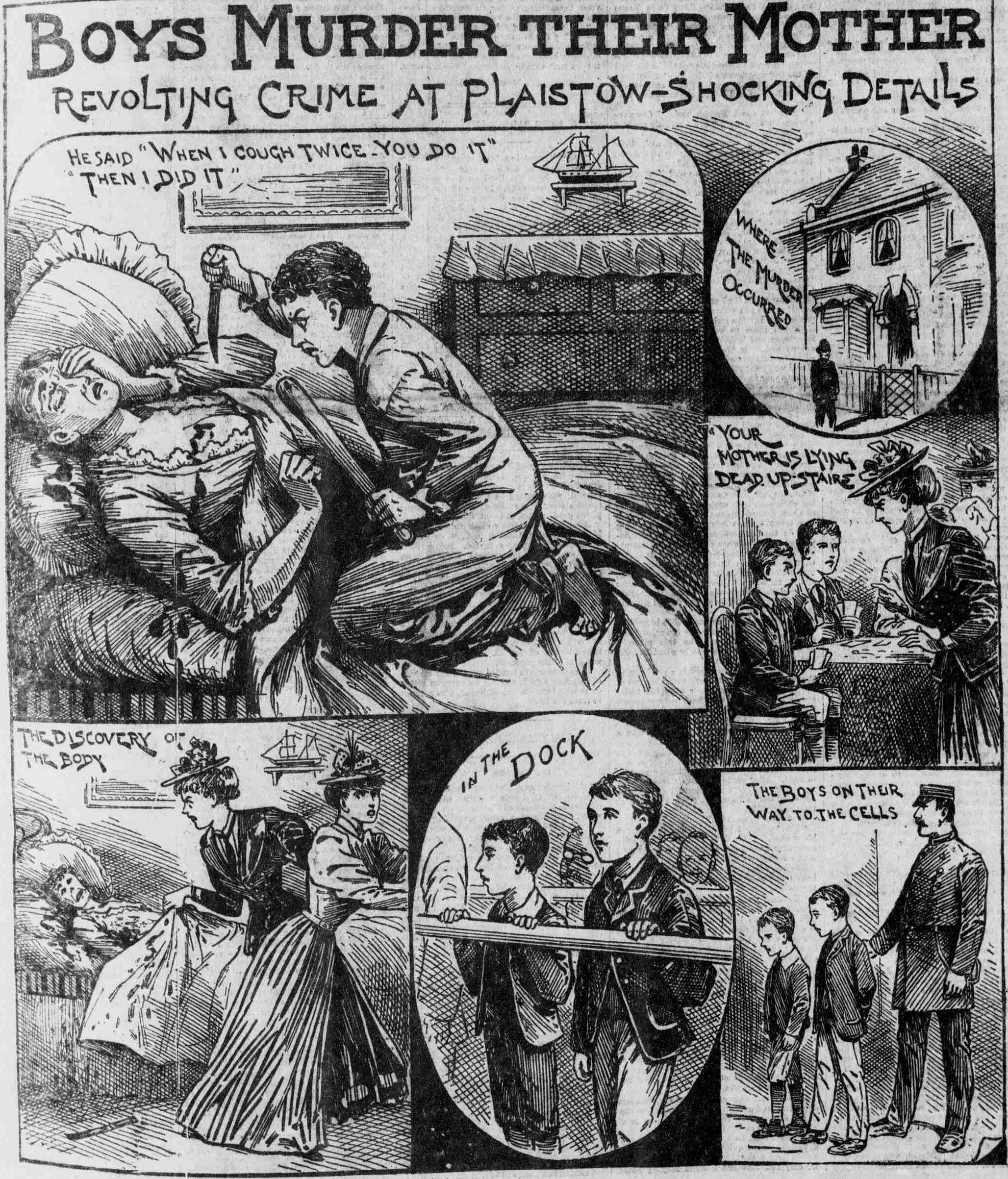

Illustrated Police News, Saturday 27 July 1895.

Newspapers throughout the country competed to report the latest news of ‘The Plaistow Matricide’. The case proved a particular sensation. Several graphic illustrations of the murder were printed in the press, tourists flocked to the Coombes’ house in Plaistow pestering neighbours for interviews and character testimonies, thousands of people mobbed the magistrates’ court in the hope of glimpsing the boy murderer. A narrative of Robert’s crime was published and adapted for stage, a melodrama staged at a penny theatre on the south bank, and a wax worker in Islington offered showmen the opportunity to buy wax-work images of the boy’s head. What made this case so sensational in the nineteenth century lends to the predicted success of Summerscale’s latest book. The idea that a young boy might be capable of wilfully killing his mother as she sleeps is horrifying. Rather than turning away in disgust, however, it is human nature to want to know more.

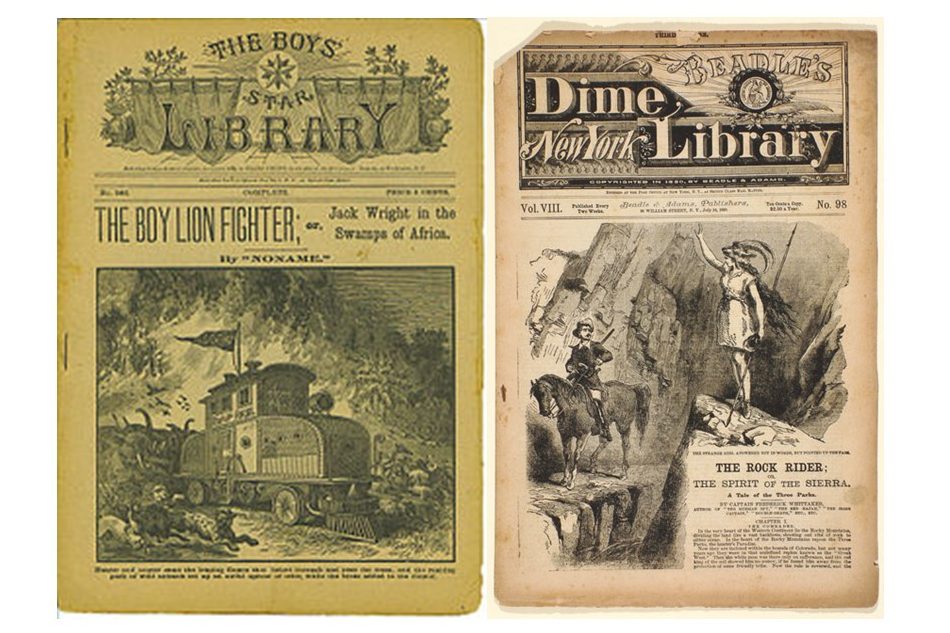

The book is divided into six sections. Part one explores Robert’s movements immediately after the murder and before his crime was detected. He takes his brother to watch cricket at Lords, they take the train to Southend-on-Sea and go fishing, they play Cowboys and Indians in the backyard and football on the street. A reader who is less well acquainted with the case does not yet know that the body of the boys’ mother is lying in the upstairs bedroom. The first three chapters read as an investigation of everyday childhood experiences in late Victorian east London. They play at the Balaam Street recreation ground, watch a melodrama staged at the Theatre Royal in Stratford and read numerous adventure stories and penny dreadfuls. Robert Allen Coombes appears to be a normal child, participating in the culture of Victorian boyhood.

Two of the penny dreadfuls in Robert’s collection

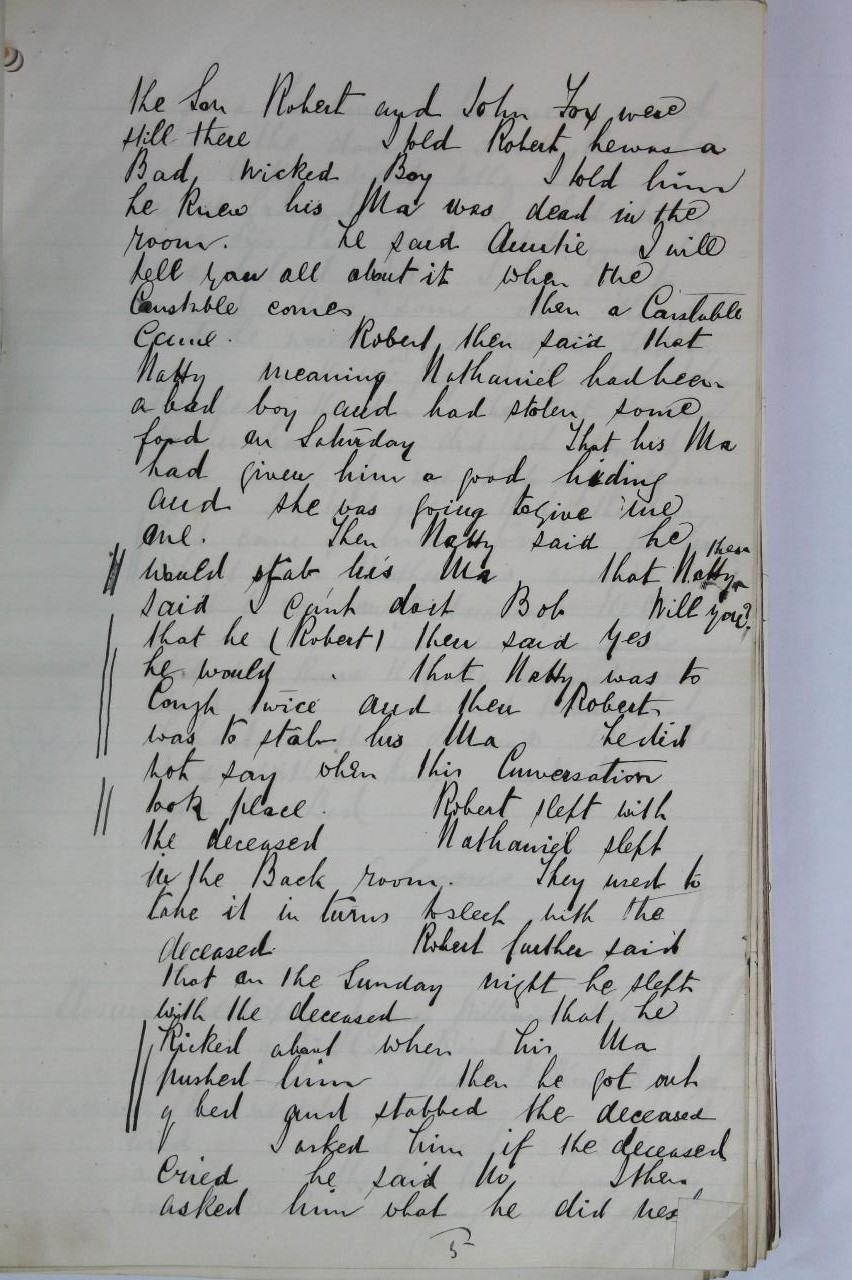

Parts two and three of The Wicked Boy focus on Robert’s journey through the criminal justice process: his arrest, the coroner’s inquest, the magisterial hearing, his time in gaol and, finally, the murder trial heard at the Central Criminal Court on the 16th and 17th of September. Summerscale skilfully weaves a narrative from the wealth of information provided in court records and articles printed in the press. Many nineteenth-century newspapers reported murder trials in considerable detail, often quoting witness statements and repeating opening and closing speeches made by lawyers. A full transcript of the trial is available to read on the Old Bailey Proceedings website. This source provides Summerscale with detailed information about the case, with accurate accounts of Robert’s movements before, during and after his arrest, and with first-person testimonies. She uses these testimonies as items of speech throughout the book. For instance Robert’s aunt shouts, ‘you are a bad, wicked boy’, when she discovers her nephew murdered his mother (p. 38). This line is taken from the aunt’s testimony in court, recalling how she discovered her sister-in-law’s body. A result of relying on court records to construct the narrative for her book is a clear, detailed and (as much as it is possible) a true account of the case. Summerscale could have sensationalised the story of murder committed by a child. Instead, she provides a book that will be of as much interest to scholars as it will to a more popular readership.

‘you bad, wicked boy’ – the aunt’s witness testimony, from the Proceedings of the Old Bailey online.

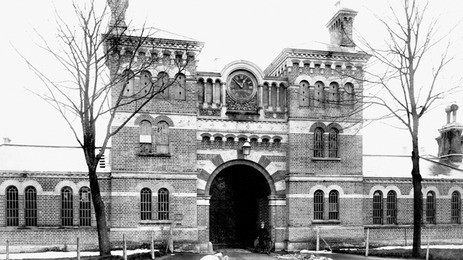

The fourth part of the book traces Robert’s life during the seventeen years he spent at the Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum. Though Robert was found guilty of killing his mother the jury considered he was insane at the time he committed the act. Rather than receiving a sentence of death, Robert was sent to serve an indeterminate period at the criminal lunatic asylum. He was the youngest person admitted to the institution by several years and was placed in Block 2 – a ward housing the more gentle and educated patients. Summerscale notes that this ward usually housed men from middle- and upper-class backgrounds. Robert had grown up in Liverpool and east London. He was the son of a merchant seaman, had attended local board schools and worked, for a time, at an iron works. His time at Broadmoor provided him with skills he would never have obtained in the outside world: he learned to play the cornet, violin and piano, he became a highly skilled chess player and grew adept at tailoring.

Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum in the 1890s

However, in my opinion this section is the weakest in the book. Access to Robert’s patient records is restricted so Summerscale is unable to provide a complete history of Robert’s experiences at Broadmoor. To get around this she offers a neat history of the institution and explores the life and crimes of some of Robert’s fellow inmates. I found this very readable, most histories require a bit of creative research to move a story forward. She explores the world in which Robert was placed, and provides readers with the opportunity to meet characters he might have met, to read about events Robert might have witnessed and to learn about the daily routines the boy murderer would have been subject to.

What I balk at is Summerscale’s tendency to play detective, analysing evidence brought to trial and coming to her own conclusions about Robert’s motive and his relationship with his mother. She reads items of evidence with a psychoanalytical approach, diagnosing Freudian tendencies in the behaviour of the boy murderer and turning to the child’s past to better understand his crime. This is certainly an interesting approach, but aside from that fact that it does not reflect the opinions and interpretations of such crimes offered by journalists and experts at the time, it is presented not as the author’s opinion but as a quasi-scientific retrospective diagnosis of Coombes. Having read numerous press accounts, the expert witness testimonies provided at the Central Criminal Court and the opinions of medical professionals in journals and magazines I have found no explicit references that promoted a psychoanalytical reading of Robert’s crime. Rather his mental aberration was explained in biological terms: he suffered head trauma during his birth and inherited a peculiar disposition from his mother.

Summerscale writes that she was intrigued by the murder committed by Coombes:

I was fascinated by Robert: in his court appearances he seemed hollow, light, scoured clean of feeling; and yet the killing suggested a catastrophic disturbance, and unbearable intensity, of emotion (p. 279).

In the final two sections of the book she traces Robert’s life after his release from Broadmoor. Did he commit any other crimes? Was he a psychopath, or just the victim of circumstance living in east London, surrounded by poverty and ill manners?

Robert immigrated to Australia in 1913. He was in military service for the entire duration of the First World War. As a stretcher-bearer he played a crucial role at Gallipoli, at the Battle of the Somme and in Flanders. He saved lives and was awarded the Military Medal for his bravery. Robert also volunteered in World War Two, lying about his age (he was 59 at the time). Summerscale dedicates the final chapter of her book to an instance of Robert’s bravery and kindness. He rescued a young boy who had been severely beaten by his father. Robert opened his home to the lad, taking him to school, helping with homework and teaching him a trade. He taught local children to play musical instruments and kept a vegetable patch, always finding time to say a friendly ‘g-day’ (p. 305). How was Summerscale able to trace this story? Well – the boy Robert saved grew into a man, a man who survived to his nineties and who gladly shared his memories of Robert Allen Coombes with the author.

Robert Coombes in the 1940s

What began as a story of a monstrous murder ends with a story of bravery and love. I’m going to admit now that I cried (properly wept) when I finished reading The Wicked Boy. Perhaps it was an outburst of emotion after having read the life story of someone who has appeared so frequently in my own research, or of jubilation that the boy murderer from Plaistow did not grow up to kill again. I think, however, that the tears were from guilt. I have treated Robert Coombes as a case – as an example of murder committed by a child. Summerscale treated him as a person. I think it important for historians to remember that we study the lives and experiences of real people – people who felt, who loved, who cried, who had wishes for the future and memories of the past. I was wrong to judge Robert Coombes by his crime alone. The murder took place on just one day of his life. He was no monster. He died a hero, and was remembered fondly.