Thomas Dixon is Director of the Centre for the History of the Emotions at Queen Mary University of London. His new research – part of the Living With Feeling project – explores the history, philosophy, and experience of anger.

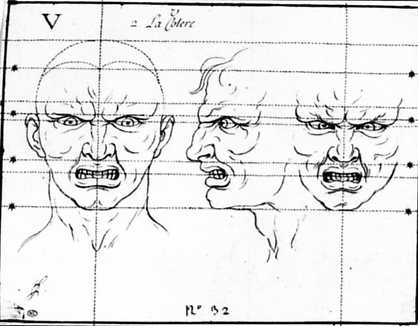

‘La Colère’ by Charles Le Brun

In this, the second in an occasional series asking ‘What is anger?’, Thomas discusses the possible answers to that question suggested by a classic work of ethnography by the anthropologist Jean L. Briggs, who died earlier this year.

He reflects on parallels between history and anthropology, describes the Inuit culture of emotional control documented by Briggs’s in her remarkable book Never In Anger (1970), and finally asks where Briggs’s research leaves the quest for a universal emotion that corresponds to the English word ‘anger’.

As a student of foreign feelings, unfamiliar words, and bizarre attitudes towards emotion found in other cultures, I like to think of myself as something of an anthropologist. The past, as has often been noted, is a foreign country and its inhabitants lived and felt in ways that it takes an effort of scholarship and imagination to recover. The historian of emotions, like the anthropologist, is all too aware of the differences between their own mindset and worldview and those of the people they are studying, while also hanging on to a sense of some shared humanity and the possibility of making real, sometimes emotional connections.

The analogy between cultural history and anthropology is a good one, although I realise with some discomfort that while plenty of historians have described themselves as anthropologists of the past, not so many anthropologists tend to line up to boast that their work is a kind of history. In any case, the parallel only goes so far. In my work as a historian I have never, for example, risked my life in an extreme climate, isolated myself completely from western civilization for months on end, been ostracized by the people I am studying, or tried to subsist on a diet made up predominantly of raw fish. Jean Briggs did all of those things as an intrepid graduate student in the early 1960s in a remote arctic region. The result was a classic work of ethnography describing the social lives and emotional dynamics of the small group of Inuit among whom she lived. It was published in 1970 and is still in print – Never In Anger: Portrait of an Eskimo Family.

It was August 1963 when Briggs arrived in an area of arctic tundra in the Canadian Northwest Territories, northwest of Hudson Bay, to study a community of only twenty to thirty-five individuals, calling themselves the Utkuhikhalingmiut – the only human inhabitants in an area of 35,000 square miles, subsisting through fishing, hunting, and trading. The Utku – Briggs mercifully abbreviates the name throughout – agreed to play host to Briggs, one of the families taking her in as their adoptive daughter. Briggs’ intention was to spend a year to eighteen months studying shamans and shamanism. It was only some time after her arrival, as she started to learn the language and ask more questions, that Briggs discovered that the Utku had in fact been converted by missionaries some decades earlier and were now all devout Anglicans. Indeed, her adoptive father – referred to by the pseudonym ‘Inuttiaq’ in the book – was the religious leader of the group and led regular prayer meetings and religious services. Without any shamans to study, Briggs had to find a new topic for her research, and she gradually settled upon the emotional dynamics of the group as her main focus.

It was August 1963 when Briggs arrived in an area of arctic tundra in the Canadian Northwest Territories, northwest of Hudson Bay, to study a community of only twenty to thirty-five individuals, calling themselves the Utkuhikhalingmiut – the only human inhabitants in an area of 35,000 square miles, subsisting through fishing, hunting, and trading. The Utku – Briggs mercifully abbreviates the name throughout – agreed to play host to Briggs, one of the families taking her in as their adoptive daughter. Briggs’ intention was to spend a year to eighteen months studying shamans and shamanism. It was only some time after her arrival, as she started to learn the language and ask more questions, that Briggs discovered that the Utku had in fact been converted by missionaries some decades earlier and were now all devout Anglicans. Indeed, her adoptive father – referred to by the pseudonym ‘Inuttiaq’ in the book – was the religious leader of the group and led regular prayer meetings and religious services. Without any shamans to study, Briggs had to find a new topic for her research, and she gradually settled upon the emotional dynamics of the group as her main focus.

Briggs’s adoptive father Kigeak (referred to as ‘Inuttiaq’ in her book) in a photo taken by Briggs in the early 1960s. Picture source: Nunatsiaq News

Briggs’s wonderful book is involving for many reasons. The descriptions of the setting, climate, and atmosphere are vivid and evocative, giving a sense of the desolate majesty and danger of the icy surroundings. The domestic details are telling too – from the endless catching, gutting and eating of fish (I started to feel despair, ennui, and nausea after a while just reading about it), to the techniques for scraping and sewing caribou hide, to the personal habits of her charismatic adoptive father Inuttiaq – fond of delivering not only moralistic sermons and prayers but also lewd jokes. The tense relationship between Briggs (known to her adoptive family as “Yinni”) and Inuttiaq is at the heart of the book, and the way that Briggs includes her own behaviour, emotions, and attitudes within the scope of her study is one of the things that made it so unusual and successful as an ethnographic study.

Never In Anger documents, then, not only the prevailing emotional regime among the Utku but Briggs’s attempts (and repeatedly failures) to conform to it. She finds herself, time and again, behaving like a kapluna (that is, a white American outsider) – too often allowing her annoyance, displeasure, and despair to become visible. The resulting tensions finally come to a head when she – believing herself to be expressing Inuttiaq’s wishes – gets into an angry confrontation with a visiting group of kapluna fishermen, who wish to borrow a canoe (having already carelessly damaged the Utku’s only other boat). Yinni’s anger with the fishermen, and then with Inuttiaq, who undermines and reverses her refusal to lend the canoe, and with herself for her failure of self-control, leads to months of unhappy resentment and ostracism.

Someone like Yinni who could so easily and frequently lose their temper was, in the eyes of the Utku, as bad as a baby or an animal. Indeed this was a standard twentieth-century Inuit belief about kaplunas more generally – that they were loud, irrational, and bad-tempered like the dogs from whom they were descended (pp. 74, 329). In this we see an ironic mirror image of the common belief among western colonizers in the nineteenth century that indigenous ‘savages’, unlike civilized Europeans, were unable to control their emotions.

Learning restraint

Expressions of strong emotions of all kinds were of vanishing rarity among the Utku. Indeed, an anthropologist visiting rural Kent would observe more outbursts of anger and sadness over my family breakfast table on any given morning than Jean Briggs documented in her entire eighteen months among the Utku. Inuttiaq, for all his emotional intensity, his strange violent fantasies, and his violent beating of his dogs, was a model of restraint when it came to other people. Inuttiaq’s wife Allaq said of her husband that he was the only parent she had known who never got angry with his children (p. 69). Speaking as the father of two young children, I find this a truly astonishing feat, if true. Briggs wrote that she too never saw Inuttiaq lose his temper with anyone. Even some of the Utku found this extreme restraint troubling. Some expressed the view that a man who never lost his temper could do terrible violence – even murder – if he did once become angry (pp. 46-47).

This Utku ideal of emotional self-control was based on a strong contrast between the rules of expression that applied to young children up to the age of about six and older children and adults. Infants and toddlers were allowed to scream and shout, throw tantrums, weep uncontrollably, and generally create bedlam. Older children and adults, however, were supposed to be in possession of an all-important quality called ihuma, which Briggs translates as ‘mind’, ‘reason’, or ‘will’ (pp. 111-12). The possession of ihuma should lead to emotional containment, self-control, and near-constant outward calm. Situations that might provoke an explosion of rage from a modern American, Briggs noted, produced nothing more than laughter, a shrug, or a ‘too bad’ from the Utku.

The thriving Utku camp at Back River on a typical day in the early 1960s, in a photo taken by Briggs. The Utku treated Briggs as kin, teaching her their ways and traditions. Picture source: Nunatsiaq News

It was not only anger, but also other commonplace feelings such as love and sadness, that Briggs was surprised to find almost imperceptible among Utku adults. The indulgence of infant emotions extended to their being shown physical warmth and affection by adults, but demonstrative loving gestures such as kisses, embraces, holding hands, or linking arms were never seen between husbands and wives or between parents and their older children (p. 117). Separations and reunions between loved ones were marked by nothing more expressive than a gentle handshake, if that. Tears too were considered inappropriate for all but the youngest infants. When a fourteen-year-old boy allowed a tear to run down his cheek when his father was about to be flown to hospital, possibly never to return, his sister laughed with others about this amusingly childish behaviour (p. 258).

In a later book, Briggs has documented the use of imaginary emotional dramas to teach young Inuit children these habits of self-control.1 Adults would provoke and tease children with tests and questions – encouraging them to be greedy, violent, or vindictive – as an indirect way to teach them the opposite virtues of generosity, calmness, and forgiveness. In a 1994 research chapter entitled ‘“Why Don’t You Kill Your Baby Brother?”The Dynamics of Peace in Canadian Inuit Camps’, Briggs explains that a heightened awareness of the threats of hostility and bloodshed led to the creation of these regimes of emotional education and control among the Inuit. And of course, of all human emotions, anger is the one most strongly associated with such threats.

Angry Jesus

In a previous post I explored some of the foundational texts of western moral philosophy, as deployed by Martha Nussbaum, as intellectual and moral tools in the restraint of anger. Another great text (or collection of texts) conveying ancient ideas about living with feelings is the Bible. And it was to the authority of God and the Bible that Inuttiaq turned for the underpinning of the Utku emotional regime – a regime which, incidentally, undoubtedly long predated the community’s conversion to Christianity. One of the recurring themes of Inuttiaq’s stark and direct sermons – one that Briggs couldn’t help but feel was directed towards her – was that God would protect people from the clutches of Satan so long as they prayed regularly and did not get angry, and such people would go to heaven. Those who did get angry, however, would be taken by Satan and used as firewood (pp. 52, 56, 257, 267-8).

Given this use of God and the Bible to justify such an extreme ban on expressions of anger, it is not surprising to learn that Inuttiaq showed some embarrassment when trying to explain the story of how Jesus angrily drove the money changers out of the temple. Jesus only behaved like this once, Inuttiaq pointed out, and the money changers were being very bad (pp. 331-2).

Now this example of Jesus’s cleansing of the temple brings us to the crux of the matter for another reason too. The Utku term used to describe what Jesus did to the money-changers was huaq – to scold – which is just one of several different words with connotations of anger. Never In Anger demonstrates what happens when someone schooled in one emotional regime has to live under the rule of a quite different regime, and struggles to adapt their beliefs, emotions and behaviours accordingly. So far, this can be framed in a fairly standard way as an example of how different human societies (whether remote from each other in time, space, or cultural distance) can have different attitudes to the emotion of anger. But of much more importance and interest as far as I am concerned is the way that it can help us to think about whether there is any such thing as the emotion of anger. Briggs herself, for the sake of brevity and convenience, generally refers in her book to people displaying ‘anger’ or ‘bad temper’. However, these English labels do not have direct equivalents in the Utku dialect. Never In Anger is a book not only about a culture with a strong apparent aversion to what we call “anger” but also one with no single equivalent concept of “anger”.

Lust in translation

In an appendix and glossary analysing Utku emotion terms and concepts, Briggs makes several observations about the impossibility of making a tidy one-to-one translation between Utku words and English words. Briggs suggests nine broad emotional ‘syndromes’, and arranges the various terms under those headings. One of the nine syndromes is ‘Ill Temper and Jealousy’ and includes eight different Utku terms, five of which relate to aggression and hostility, and three to possessiveness or unhappiness of other kinds (pp. 328-37). The five terms relating to aggression and hostility are huaq – to scold, as Jesus did in the Temple; ningaq – to aggress physically; ningngak – to feel or express hostility; qiquq – to be clogged up with foreign matter, to feel hostile; urulu – to feel, express or arouse hostility or annoyance (p. 329).

Let me make four quick points about this. First, and most obviously, as I have said, there is no Inuit word for “anger”. Secondly, it is notable that there is no reference anywhere to the idea that any of these Inuit words includes a necessary reference to revenge or pay-back (which is considered a defining feature of orge – the Ancient Greek philosophical concept of anger adopted by Nussbaum and others). Thirdly these words are primarily, though not exclusively, terms for outward actions – such things as shouting, scolding, threatening, and physically attacking. The Inuit vocabulary as translated by Briggs (and this is reinforced also by another recent linguistic study) is primarily a behavioural one.2 So, whatever it is that is standing in the place of “anger” or “bad temper” in the worldview of the Utku seems to have been more a set of behaviours than a set of feelings. Finally, Inuit languages do not seem to have an equivalent category to the English ‘emotion’ at all, so their second-order moral and psychological beliefs about shouting, attacking, and hostility will not be based on the same model of the mind as is familiar in modern academic psychology.

The historian of emotions and the anthropologist, then, do have one more thing in common. Each needs to pay close attention to language, to problems of translation and to the multiple meanings of even apparently familiar emotion words if they are going to do justice to the experiences and motivations of the people they are studying. This lesson applies, in fact, even within a relatively short historical period and in a single language, even before facing up to the formidable problems that attend translations of terms across languages and cultures.

We have already seen in these first two blog posts that the simple word ‘anger’ when used by a philosopher, an anthropologist, and a historian may refer to three quite different things. And even that is probably a ludicrously conservative estimate, as future posts will show.

Follow Thomas Dixon on Twitter:@ThomasDixon2016

Learn more about the Living With Feeling project

More blog posts relating to Living With Feeling

Learn more about Jean Briggs:

Obituary of Jean Briggs in the Toronto Globe and Mail

Two hour-long interviews with Jean Briggs – ‘Never in Anger and Beyond’ – broadcast on the CBC ‘Ideas’ programme in 2011 – Part One and Part Two.

Feature article in the Nunatsiaq News about Jean Briggs’s and her four decades of work with the Utku

A Memorial University Gazette article about Jean Briggs’s book Inuit Morality Play

References:

1 Briggs, Jean L. Inuit Morality Play: The Emotional Education of a Three-Year-Old. Yale University Press, 1999.

2 Fortescue, Michael. “The Semantic Domain of Emotion in Eskimo and Neighbouring Languages.” In The Lexical Typology of Semantic Shifts, edited by Päivi Juvonen and Maria Koptjevskaja-Tamm. Cognitive Linguistics Research 58. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2016, pp. 285–333.