Margery Masterson is a Research Associate at the University of Bristol. She works on Victorian masculinity and the twin themes of militarization and memorialisation. She is currently working on the Victorian volunteers craze of the 1860s.

Margery Masterson is a Research Associate at the University of Bristol. She works on Victorian masculinity and the twin themes of militarization and memorialisation. She is currently working on the Victorian volunteers craze of the 1860s.

I often pass an old man with his dog on my usual evening walk. There’s a grey tinge to the dog’s tufted black fur, but his short-legged gait is still brisk, punctuated by frequent stops to allow his owner to catch up. With the shortening days, the dog wears a collar of flashing red lights to protect him from cyclists, making him look rather like a homemade Christmas ornament.

We exchange pleasantries and then I return to my audiobook. The shape of the man and the dog soon fades back into the gloom and all I can see are the blinking red lights. Now moving, now patiently pausing. I am currently immersed in The Forsyte Saga (1906-1921). After concluding a whirlwind plot of adulterous affairs and ruinous lawsuits in the first volume, John Galsworthy slows the pace almost to a standstill for the ‘Indian Summer’ of Old Jolyon.

At eighty five, Old Jolyon’s left alone at home while his family’s on holiday. Almost alone. Balthasar, a would-be Pomeranian, watches as Old Jolyon seeks out the company of the beautiful Irene. In his sudden, deep need for Irene’s company, Old Jolyon comes to resemble his animal (‘his eyes grew sad as an old dog’s’) and it is his dog who notices Old Jolyon’s rapid deterioration: ‘Only the dog Balthasar saw his lonely recovery from that weakness; anxiously watched his master go to the sideboard and drink some brandy, instead of giving him a biscuit .’ (Indian Summer of a Forsyte Chapter IV)

I was retracing my steps homeward when Old Jolyon shuffled outside with Balthasar to wait under a tree for Irene one last time. The impending ending flashed across my mind. ‘The dog placed his chin over the sunlit foot. It did not stir … suddenly he uttered a long, long howl.’ I echoed this howl with a sudden, unstoppable sob. My own reactive grief seemed wildly out of proportion to the peaceful death of a fictitious octogenarian. What was so sad about this scene?

The only time I can remember feeling such simple devastation was watching children’s films featuring old dogs. Memorable among these canines is the old bloodhound in Lady and the Tramp (1955) who, recovering his sense of smell, tracks the villain’s carriage only to be run over. Even more heartrending is the old golden retriever in Homeward Bound (1993) who, having crossed the entire United States to be reunited with his boy owner, is injured falling into a pit and cannot climb out. The old dog as an old man reaches its apogee in Disney entertainments. Old dogs literally speak in the voices of old man and display, especially in the animated forms, human movements and expressions.

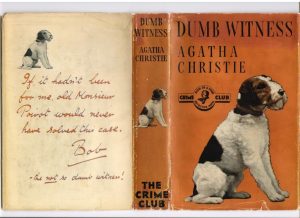

The pedigree of this synthesis of human and non-human forms is far older than Disney. Novelists in particular have long been drawn to the idea that dogs are unique witnesses to human suffering and death. Modern detective stories have always been interested in dogs as witnesses to human death – and intrigued by the problem of a witness that cannot speak. From Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes short story Silver Blaze (1892) and the dog that famously ‘did nothing, Watson’ to Agatha Christie’s Dumb Witness (1937) where Hercule Poirot deducts who the real killer is by observing the dog Bob.

Real-life celebrity dogs of the period performed hyper-masculine action ‘heroics’, like those of the sled-dog Balto, but they also excelled, as Liz Gray has discussed in this blog, in the more passive rites of mourning like Greyfriars Bobby. Dogs often mitigate the loneliness and isolation of illness, but they also bear witness to it in ways that are not always easy for historians to access. Victorian novelists were fascinated by the ways in which dogs externalized the unspoken or un-witnessed suffering of humans.

![Sol Eytinge, ‘Dora and Miss Mills’. Wood engraving from Dickens's David Copperfield in the Ticknor and Fields (Boston), 1867, Diamond Edition [Victorian Web].](https://emotionsblog.history.qmul.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/dora-and-miss-mills-225x300.jpg)

Sol Eytinge, ‘Dora and Miss Mills’. Wood engraving from Dickens’s David Copperfield in the Ticknor and Fields (Boston), 1867,

But this projection is a two-way process. The suffering humans also take on doglike qualities. Magwich in Great Expectations (1860-1), already ‘very like the dog’ in his rough mannerisms, becomes doglike in his lonely and futile longing for Pip’s regard and affection. In The Old Curiosity Shop (1840-1), Little Nell’s ‘panting dog’ of a grandfather visits her grave everyday for three months and then dies himself with doglike loyalty.

Collar of Keeper from Deborah Lutz, Relics of Death in Victorian Literature and Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

Indeed, ‘doglike’ characters seem particularly easy to twist from menacing men into pitiable specimens. Heathcliff, likened to a ravening wolf early on in Wuthering Heights (1847), takes on the more pathetic traits of a domestic dog in his mourning of Cathy. Emily Bronte’s own chief mourner was her dog, a large male mastiff called Keeper. The mastiff was an integral part of Bronte’s funeral procession and became a ‘living monument’ to her afterwards.

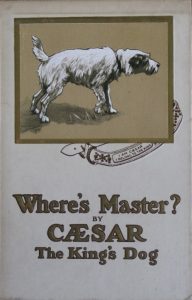

Where’s Master by Caesar the King’s Dog (1910). For more on this story see Cambridge’s Tower Project blog.

Bereaved canines act less as gate keepers and more as gateways into private human grief. This was especially true of King Edward VII’s wire fox terrier Caesar. After he prominently walked in the King’s 1910 funeral cortege, a first-person account of Caesar’s intimate view of royal bereavement was anonymously published. Where’s Master? admitted commoners into the King’s bedchamber at the moment of his death, increasing the pathos of his passing but, perhaps, lessening the awe of the occasion.

So what is it about dogs and grief that humans find both so heartbreaking and so familiar? Marjorie Garber writes in Dog Love (1996) about this quandary over pet bereavement: ‘This, I think, is part of the poignancy of the relation between human being and dog: we sense in dogs so much in the way of sympathy for our moods, grief’s, losses – and that we are so powerless to explain loss, death, and sadness to them. (Garber, p.252)

If this is true – and I think that it is – then so is the reverse. If humans pity dogs’ uncomprehending and inarticulate response to human death, we also find it particularly sad when humans are rendered similarly dumb – whether by their intrinsic personality or social conditioning. It is conspicuous that, at least in nineteenth and early twentieth century literature, female characters never suffer from ‘doglike’ grief whereas upper-middle class British men at the turn of the twentieth century, John Galsworthy’s speciality, typify an inarticulate, ‘canine’ response to bereavement.

If, as Charles Fraser has argued in this blog, ‘connection entails reciprocity’, then we must look for a genuine exchange between human and non-human animals rather than ventriloquism. I suspect there is a possibility for a human and a dog to share one another’s grief – the old man and the old dog shuffling around the house in silent communion – but I am suspicious of attempts to give a human voice to non-human animal emotions. I doubt that the ‘speaking’ sentimental canines of fiction and of history are anything more than a reflection of human emotion.

Yet, as Galsworthy shows, humans’ ventriloquism of dogs reflects real emotions. He extends the dog Balthasar’s life for a ludicrously long time so that the dog’s death can presage another family bereavement in the second volume of The Forsyte Saga. ‘What is it, my poor old man?’ says Young Jolyon to the dying dog. Later, turning to his son as they finish digging Balthasar’s grave, ‘old man, I think it’s big enough.’ (In Chancery, Part II, Ch. X) Hearing this, you simultaneously realize two things: first that the son will die, and second that his father will never be able to fully understand or express his sadness at this bereavement.

Young Jolyon will become, like his father, a sad old dog.

Want to read more posts about animals and emotion?

Try Thomas Dixon’s ‘Emotional Animals No. 1’ or Liz Gray’s ‘Loyalty and a Dog Called Bobby’ or check out our ‘Emotional Animals’ category.