Dr Thomas Dixon is the Director of the Centre for the History of the Emotions at Queen Mary, University of London. Here he writes about the representations of tears and weeping in Shakespeare’s first tragedy.

I have been researching the history of crying for several years. This interest started back in 2009 when I was invited to an event on Darwin and the emotions and began thinking again, for the first time in ages, about The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872). This is a surprising and striking book in many ways, including its emphasis on the purposelessness of emotional expressions, and its pioneering use of research questionnaires and photographs. But what caught my attention in 2009 was the chapter on ‘Special Expressions in Man: Suffering and Weeping’, including the assertion that ‘Englishmen rarely cry, except under the pressure of the acutest grief; whereas in some parts of the Continent the men shed tears much more readily and freely.’

My attempt to position those three simple words of Darwin’s – ‘Englishmen rarely cry’ – in the longer histories of science, emotion, and national identity, has now led me back to Shakespeare, and to a play currently being revived by the RSC. The Lamentable Roman Tragedy of Titus Andronicus, to give it its full title, was first performed in 1594 and it serves as a microcosm of early modern weeping, understood as a kind of performance, a work of nature, and an outward token of inner states.

The play is a revenge tragedy of astonishing violence: bowels, limbs, heads, hands and tongues are lopped and hewn. Virtually all the protagonists end up dead – many of them in a final blood-soaked show-down in which Titus kills his only daughter, the defiled Lavinia, who has been raped and mutilated by Queen Tamora’s sons, whom Titus now serves in a pie to their mother, before being promptly killed by the emperor, who is in turn killed by Titus’s remaining son Lucius. There is much sorrow and plenty of weeping – although not during the final scenes of tearless and pitiless revenge. The play is a very useful one for my purposes, as its writing, performance and reception can be used to explore medical ideas about the body and mind, as well as the histories of tragedy, Stoicism, religion, and morality.

As performed on the London stage in 1594, Lavinia would have been portrayed by a boy-actor and not a woman. We do not know whether he produced tears himself, but it is likely that some of the audience would have been moved to tears by this spectacle. And this reinforces the strangeness of weeping as something simultaneously the acme of emotional sincerity and the height of theatrical fakery. Tears of sorrow shed by the audience in sympathy with a young boy in good health pretending to be a mutilated woman in the midst of a horrific family revenge in ancient Rome might be interpreted as evidence of admirable powers sympathy or of a pathological susceptibility to dangerous, false and unreal passions, as anti-theatrical polemicists claimed.

Weeping was indeed an act, and yet at the same time a work of nature – something elemental, which came easily to children and women because they were more under the sway of the passionate parts of nature, and more naturally moist. Weeping, for early moderns, was like urinating, sweating, or vomiting. It was an ‘expression’ in the literal sense of a squeezing out or excretion. We can trace our own ideas about weeping as a kind of ‘emotional incontinence’ back to this humoural view of the body, according to which tears were a kind of ‘excrement’ – a liquid distilled from the blood, spirits, humours or vapours, produced by the heart or brain, and pressed out through the eyes.

For the English clergyman and physician, Timothy Bright, writing his Treatise on Melancholy in 1586, tears were ‘the brain’s thinnest and most liquide excrement’. Robert Burton, in his Anatomy of Melancholy, in 1621, described sweat and tears within a similar humoural system, in which the principle humours, or fluid parts of the body were blood, phlegm, choler and melancholy. ‘To these humours,’ he noted, ‘you may add serum, which is the matter of urine, and those excrementitious humours of the third concoction, sweat and tears.’ René Descartes, in his 1649 treatise on The Passions of the Soul, treated tears and sweat together too: as the products of vapours issuing from the body. For Descartes, weeping was a kind of sweating from the eyes. Only after the 1660s did anatomists, following Nicholas Steno, teach that tears were produced by the lachrymal glands.

The scenes in Titus Andronicus in which tears flow volubly like forces of nature, connect with this sense of bodily overflow. Shakespeare identifies human tears with all the seasons and all the waterworks of nature – streams, rivers, and oceans; showers, storms and life-giving rain. Lavinia and Titus at different points refer to their ‘tributary tears’ of mourning – alluding simultaneously to tributes to the dead and to natural rivulets. Lavinia is described as a pure spring, muddied by her rape, and Titus’s grandson is described both as a ‘tender sapling’ and a ‘tender spring’ – tender in the sense both of youthful and moist. Titus tells the boy, ‘thou art made of tears’.

Titus’s depicts his own tears as forces of nature, describing himself as the sea and the earth; Lavinia as the sky (or ‘welkin’) and wind.

When heaven doth weep, doth not the earth o’erflow?

If the winds rage, doth not the sea wax mad,

Threatening the welkin with his big-swollen face?

And wilt thou have a reason for this coil?

I am the sea; hark, how her sighs do blow!

She is the weeping welkin, I the earth:

Then must my sea be moved with her sighs;

Then must my earth with her continual tears

Become a deluge, overflow’d and drown’d;

For why my bowels cannot hide her woes,

But like a drunkard must I vomit them.

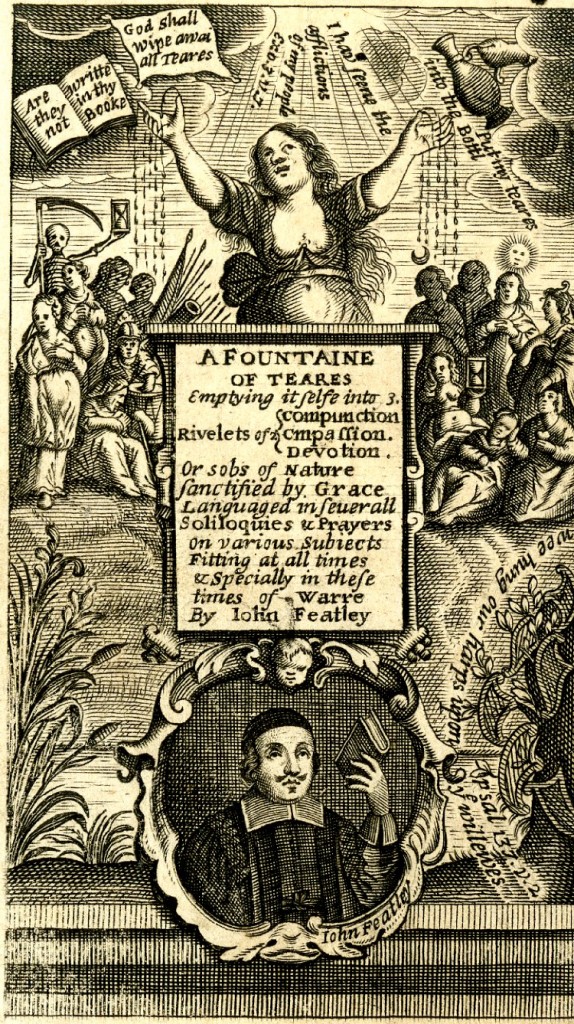

That final image of vomiting out woes reinforces the understanding of tears as a voiding of bodily waste. This moment is the high water mark of Titus’s epic, meteorological, humoural, natural weeping. And it is part of a literary tradition of tears that continued into the seventeenth century – including religious texts by Catholics, Puritans and Anglicans. In the latter category John Donne’s 1623 sermon on the text ‘Jesus Wept’, George Herbert’s 1633 poem ‘Grief’, and the 1646 devotional work by John Featley, pictured below, entitled A Fountain of Teares (1646) are notable examples.

Herbert’s poem on grief starts:

O Who will give me tears? Come all ye springs,

Dwell in my head & eyes: come clouds, & rain:

My grief hath need of all the watry things,

That nature hath produc’d.

And in Descartes’s treatise on the passions of the soul we find a physical rationale for the identification of tears with natural aquatic processes. For Descartes weeping and raining are not just metaphorically but literally the same thing; both are instance of vapours, in the body or in the air, being converted into water – as rain or as tears, respectively. This occurred when the vapours were more abundant and less agitated than usual. So, when weeping eyes are described as ‘rainy’ in Titus Andronicus, Descartes, at least, would not have read that as a metaphor. Renaissance bodies were weather systems, with their vapours, humours, and liquors, flowing like tributaries, amassing like oceans, and falling like rain.

We can also gain an insight into the meanings of Titus’s tears by turning to medical texts of the period. Bright’s treatise on melancholy, which Shakespeare may have read, was published a few years before the play was first performed. Here we learn something interesting about the cessation as well as the production of tears. Learned Elizabethans had religious, philosophical, medical, and political reasons to be afraid of excesses of passion, including sorrow, and we can read Titus Andronicus as a reflection on the dangers of excessive weeping, as well as on the monstrosity of those who do not weep.

Tears are repeatedly shown, in the play, to impair the functions of the rational mind. On more than one occasion tears choke or interrupt an attempt at articulate speech. Tears are signs and symptoms of strong passions, themselves widely conceived as diseases of the soul. The Roman Catholic writer Thomas Wright, in his 1601 work on The Passions of the Minde, wrote that there were three main consequences of inordinate passions: ‘blindness of understanding, perversion of will, and alteration of humours; and by them, maladies and diseases’. And these are precisely the effects that Titus’s inordinate sorrows seem to have on him.

After the speech in which Titus declares ‘I am the sea’ and ‘she is the weeping welkin’, a messenger enters the stage carrying two heads and a hand. The heads belong to Titus’s sons, and the hand is Titus’s own, chopped off by himself and misguidedly offered as a ransom for his sons’ lives. This mocking of Titus’s pleas for mercy by the execution of his sons, and the scornful return of his hand, is the final blow. This is when the crying stops. Titus in fact responds with laughter. His brother protests that this is unfitting. Titus replies: ‘Why? I have not another tear to shed. Besides, this sorrow is an enemy, And would usurp upon my watery eyes, And make them blind with tributary tears.’

From this moment, Titus weeps no more and, pretending to be mad, he sets out to exact his clear-eyed, dry-eyed revenge on Tamora and her sons, whom he lures to their doom in a piece of weird and macabre clowning, which ends with him slitting their throats, making them into a pie, and serving it to their mother at the feast of death at which he also kills Lavinia – ‘her for whom my tears have made me blind’. Surely, however, Titus is not pretending to be mad. He is mad. His dry eyes show not that he has mastered his sorrow but that his sorrow has mastered him.

It was widely agreed in treatises on the passions and on melancholy, throughout the period, that tears were signs of moderate, but not extreme sorrow. That was the view of Aristotle, and was echoed by Bright in 1586, by Montaigne in his Essays, by Descartes in his treatise on the passions of the soul, and by Walter Charleton in his Natural History of the Passions of 1674. Extreme sorrow, according to medical authorities of the period, could lead to physical illness, could take the form of melancholia, could drive people mad and could dry up their tears. The inability to weep, in turn, could cause madness, or even death.

Timothy Bright wrote of the passion of sorrow that ‘if the perturbation be too extreame, and as it were ravisheth the conceite and astonisheth the heart’ then tears are dried up and other, stronger movements replace them, ‘as voydance of urine, & ordure’. This final possibility is not explored by Shakespeare, but in other respects Titus, described in the play as ‘the woefull’st man that ever lived in Rome’, is a textbook example of the progress of the passions. His conceit is ravished, and his heart astonished. Titus’s abundant weeping in inordinate passion is replaced by a destruction of the mind, a stupidity of heart, and a dryness of the eyes: ‘I have not another tear to shed’.

In Titus Andronicus, the final tears of the final act belong to a young boy – Titus’s grandson. The boy’s father, Lucius, Titus’s only remaining son, addresses the child in words that are surely also addressed over his head to the theatre audience beyond:

Come hither, boy, come and learn of us

To melt in showers.

What Shakespeare presents his audience with here is a task – somehow to learn to weep without becoming morally and mentally deranged, without going blind, without losing the power of speech. More importantly he provides them with an activity through which to make the attempt – the collective witnessing of a classical tragedy. And thanks to Shakespeare, gathering in theatres and weeping over tragedies – experiencing a sympathy of woe – became a part of the English national character, noted by foreign visitors, long before the tide turned so that it would become possible for someone to claim that ‘Englishmen rarely cry’.

This post first appeared in the June 2013 issue of Viewpoint, the magazine of the British Society for the History of Science. Thomas Dixon has also reflected on the history and meaning of tears in a BBC Radio 3 Sunday Feature, and an article for Aeon magazine.

Pingback: Violence, vomit, and hysteria: An interview with Rose Reynolds | The History of Emotions Blog