Thomas Dixon is Director of the Centre for the History of the Emotions at Queen Mary University of London. His books include From Passions to Emotions (2003) and Weeping Britannia: Portrait of a Nation in Tears (2015).

Thomas Dixon is Director of the Centre for the History of the Emotions at Queen Mary University of London. His books include From Passions to Emotions (2003) and Weeping Britannia: Portrait of a Nation in Tears (2015).

Following on from a post by Markus Wagner and Sofia Vasilopoulou about the role of emotions in determining the result of the EU referendum, here Thomas tries to keep up with some of the emotional responses the result has produced from voters, politicians, and journalists.

“…let grief Convert to anger; blunt not the heart, enrage it.”

Macbeth (4.3.228-9)

For a historian of emotions interested in how social, linguistic, and emotional changes happen in tandem, the last few months have been fascinating. The scene had been set for me back in November 2015 when Oxford Dictionaries announced that their Word of the Year was not a word at all, but a crying-face emoji. This pictograph had been chosen ahead of the rest of a shortlist which included the term ‘Brexit’. Our technology, our language, our politics, and our feelings were already evolving together. In the last few weeks this process has accelerated to a frantic pace. I started writing this post on political emotions many times, but found myself repeatedly outpaced by the speed of the Brexit melodrama.

For a historian of emotions interested in how social, linguistic, and emotional changes happen in tandem, the last few months have been fascinating. The scene had been set for me back in November 2015 when Oxford Dictionaries announced that their Word of the Year was not a word at all, but a crying-face emoji. This pictograph had been chosen ahead of the rest of a shortlist which included the term ‘Brexit’. Our technology, our language, our politics, and our feelings were already evolving together. In the last few weeks this process has accelerated to a frantic pace. I started writing this post on political emotions many times, but found myself repeatedly outpaced by the speed of the Brexit melodrama.

So, to start with there was all that new language to think about – Brexit and Bremain had already become staples of political discussion – but now people were getting carried away and prefixing pretty much anything with ‘Br-‘. We were all on the edge of a Brexistential crisis, and I was happy to get into the spirit of things on the morning of the vote:

Right, I'm having #Brcoffee and #Brtoast then I'm going to #Brvote #Bremain. And then tomorrow our spelling will return to normal.

— Thomas Dixon (@ProfThomasDixon) June 23, 2016

I wasn’t feeling so cheery the next day, having watched with horror as the results came in, and seen Nigel Farage proclaiming victory for Leave. An opinion poll trying to get ‘Inside the mind of the voter’ found that many Remain voters had been reduced to tears by the result and were feeling emotions of sadness, frustration, and anger. It was all getting very Bremotional. On social media, several people compared their feelings of loss with the famous five stages set out by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross in her 1969 book On Death and Dying, based on interviews with dying patients.

Brenial

Branger

Brargaining

Brepression

Bracceptance#Brexit— Nolen Gertz (@ethicistforhire) June 24, 2016

Another popular version of this idea was a slightly more elaborate seven-stage model:

Of all of these emotional responses, anger – or should I say ‘Branger’? – was especially prominent in the hours and days after the result was announced. The Green Party tried to recruit new members by harnessing their emotions of ‘disappointment and anger’:

Let’s turn today’s disappointment & anger into change – join us now to make it happen: https://t.co/N7IGRsUalw pic.twitter.com/ymT4KrLe49

— The Green Party (@TheGreenParty) June 24, 2016

When leading figures from the arts were asked by the Guardian to respond to the referendum result, many mentioned anger, alongside emotions of shame, revulsion, and confusion. The playwright Lucy Prebble declared ‘I feel nothing but rage’, and went on to list Cameron, Farage and Leave voters as the targets of her fury. Nick Clegg wrote an article for the Financial Times, which was an outpouring of anger – directed not at Leave voters – but at the Prime Minister who had agreed to the referendum and the Leave campaigners who had won voters round:

I am angry that my children’s future has been put at risk by a needless referendum. Angry at the brazen mendacity of a Leave campaign which has no idea what happens next. Angry at the careless elitism of Michael Gove, Boris Johnson, Steve Hilton and other leading Brexiters, parading themselves as tribunes of the people from their gilded worlds in Westminster, North London and California.

It was still only Friday 24th June and I already had far too many opening paragraphs for this blog post. A whole post about the nature of anger now seemed like the best idea, and I started to think about this while also writing a couple of short talks about my new work on anger for the ‘Living With Feeling’ project. I was also intrigued to learn from the research of Markus Wagner and Sofia Vasilopoulou that voters who were angry about the EU were more likely to vote Leave than those who were fearful. What are politicians doing, I asked myself, when they invoke this anger? Why were some commentators impressed by the apparently genuine anger shown by David Cameron when he exasperatedly demanded that Jeremy Corbyn should resign, during Prime Minister’s questions? Is there a significant difference between the anger of a Liberal Democrat and the anger that drives a UKIP voter (discussed here by Nick Robinson in 2014)? Is political anger something physiological, or moral, or both? What is the relationship between grief and anger? Can one be converted to the other, as suggested in the quotation from Macbeth in the title of this post? Or was Malcom X right that it was only anger, and not tears, that could bring political change?

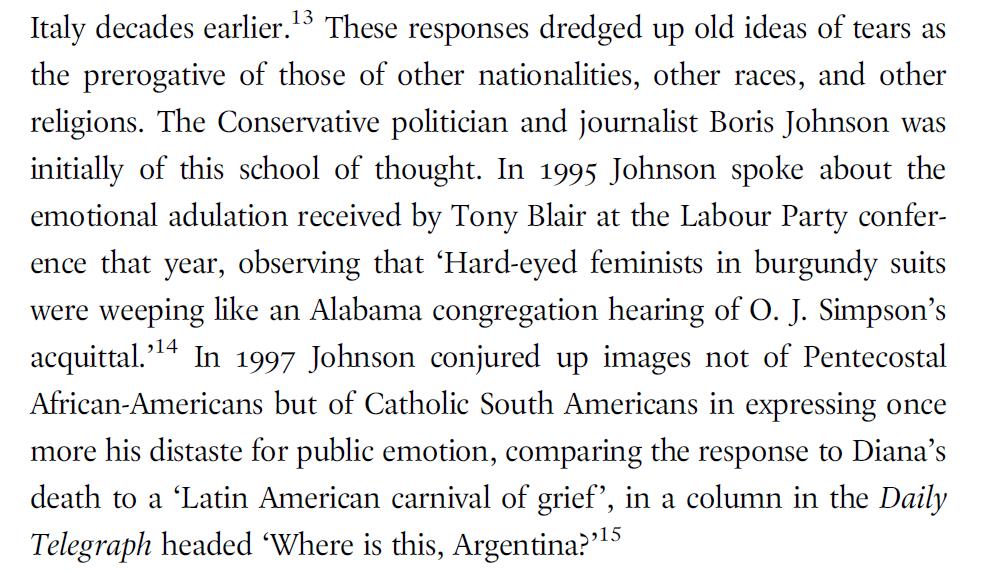

But my answers to these questions would have to wait a bit longer, as now my old research theme of tears and emotions was making a comeback. For a few days after the announcement of the EU referendum result, it seemed as though the feelings of, and about, Boris Johnson would be at the heart of the Brexit story. In Johnson’s column in the Telegraph published on 27th June, he wrote about the need to reach out to those Remain voters who had feelings of ‘dismay, and of loss, and confusion’ – those 16 million voters who, he noted, did ‘what they passionately believe was right’. OK, I thought, that’s interesting that Johnson is now so interested in political feelings and passions – that will be a good starting point for my blog post, especially since he used to be so down on emotions. As I noted in Weeping Britannia, Johnson has long associated tears with foreigners of various kinds:

From Thomas Dixon, Weeping Britannia (2015), p. 304.

But three days later Johnson had been stabbed in the back by his erstwhile sidekick Michael Gove and was no doubt having some pretty strong feelings of dismay, and loss, and confusion of his own. He was no longer the emotional focus of Brexit. The melodrama had moved on, leaving Johnson fuming about the atmosphere of ‘hysteria’ in the country. The ‘contagious mourning’ was giving him unwelcome flashbacks to that emotional Diana moment nearly two decades ago. Not for the first time, it was as though he had gone to sleep in Islington and woken up in Buenos Aires or, perhaps even worse, at the dawn of Blair’s Britain.

Having given up on Boris Johnson, and after another hectic week had passed, I thought Andrea Leadsom was going to be the protagonist to focus on. She gave an interview to The Times in which she seemed to claim that being a mother gave her an electoral edge over the childless Theresa May in the contest to succeed David Cameron. Leadsom herself was one of the first to react to the article on Twitter – with very strong emotion:

Truly appalling and the exact opposite of what I said. I am disgusted. https://t.co/DPFzjNmKie

— Andrea Leadsom (@andrealeadsom) July 8, 2016

@thetimes @RSylvesterTimes this is the worst gutter journalism I've ever seen. I am so angry – I can't believe this. How could you?

— Andrea Leadsom (@andrealeadsom) July 8, 2016

But soon the emotional and angry Andrea Leadsom – reportedly reduced to tears by the hostile response that interview provoked – had gone the same way as all the other potential rivals to the notably restrained Theresa May. So Leadsom’s feelings are no longer the story either and the focus has switched not only to the new Prime Minister Theresa May but also to the woman who would like to lead the opposition to her government, Angela Eagle.

When she announced her resignation from Jeremy Corbyn’s shadow cabinet, Eagle gave several interviews in which she often seemed on the verge of tears – as in the last few moments of this one for the BBC. Then this morning – that’s the morning of Tuesday 12th July for those trying to keep up – just as I was yet again trying to find a way to tie all this emotion together, I turned on the radio at precisely this moment on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme, as John Humphrys asked Angela Eagle whether a potential leader should be susceptible to tears:

“I’m not crying now.”

John Humphrys asks Angela Eagle if she's ruthless enough for leadership. #R4Todayhttps://t.co/b1ITWo6U7V

— BBC Radio 4 Today (@BBCr4today) July 12, 2016

Do we really want a leader, Humphrys asked, who might have to face up to someone like Vladimir Putin, but could be reduced to weeping by the pressure of doing so? Never mind the fact that Putin himself seems less averse to tears than John Humphrys might think (or indeed than John Humphrys seems to be himself), Eagle responded that she thought it perfectly appropriate for politicians to be in touch with their emotions. Humphrys still wasn’t satisfied. He put it to Eagle that he couldn’t imagine Theresa May shedding tears, and that politicians should be able to control their emotions even when under stress. As I listened with my usual mixture of disbelief and resignation to Humphrys’s line of questioning, Eagle responded firmly – possibly angrily – ‘Well, look, I’m not crying now, am I?’

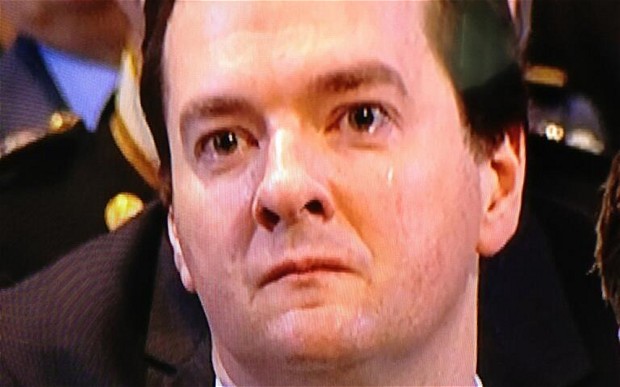

John Humphrys has form on this subject, and was another one of those I wrote about in Weeping Britannia. When George Osborne shed a tear at Margaret Thatcher’s funeral, he too was grilled by Humphrys on The Today Programme, about whether he was generally the ‘sort of person’ who wept, rather than being too ‘macho’ to show his feelings.

John Humphrys has form on this subject, and was another one of those I wrote about in Weeping Britannia. When George Osborne shed a tear at Margaret Thatcher’s funeral, he too was grilled by Humphrys on The Today Programme, about whether he was generally the ‘sort of person’ who wept, rather than being too ‘macho’ to show his feelings.

So, despite my attempts to move on from tears to anger, from the Diana effect to Brexit rage, politicians and commentators keep dragging me back, kicking and weeping, to my previous research project. So, I thought it would be appropriate to end this chaotically emotional post with a paragraph that I cut from the final text of Weeping Britannia, but which is now particularly apt, given Theresa May’s installation as Prime Minister, and John Humphrys’s assertion that he couldn’t imagine her crying.

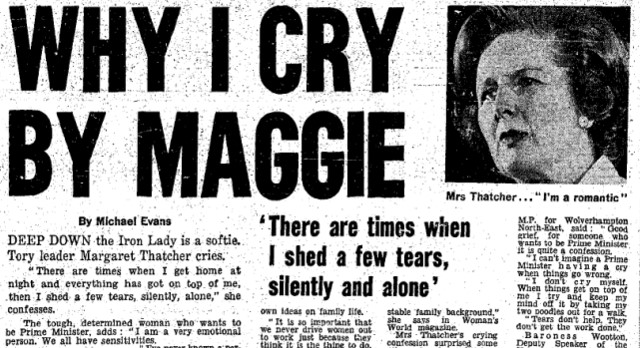

I wrote the following paragraph in 2014, having read an interview with Theresa May in Total Politics in 2012. It had made me think about the way politicians historically have deployed tears, and especially how Margaret Thatcher had done so to try to soften her image in the 1970s and 1980s. In 1978, for instance, Thatcher had given an interview to Woman’s World in which she confessed to sometimes crying after a stressful day. This was pounced upon by the tabloid press with headlines like this one in the Express:

So, back in 2014, I was thinking about all of this, and the need for Theresa May to reconsider her own emotional style, when I wrote as follows:

The only woman currently considered a likely candidate to succeed David Cameron, and who would face comparisons if she did so with the Conservatives’ first and only female leader to date, is Theresa May. In an interview in 2012, Theresa May, like Margaret Thatcher before her, was asked to reveal her ‘softer side’. In response she spoke about her love of shoes, cookery, and walking. ‘Ask what makes her cry, though’, the interviewer complained, ‘and the defences go up again. “I’m not somebody who often tears up in public,” she says.’ Politicians each have their own emotional style, and Tony Blair proved that emoting need not be accompanied by tears, but Theresa May will need to do better than this if she wishes to satisfy the post-Thatcher appetite for public displays of private emotion. David Cameron should monitor his Home Secretary’s future interview performances carefully. If one appears under the headline, ‘Why I Cry by Theresa’, he will know that her ambitions have reached a new level.

But in the newly hyper-emotional world of post-Brexit Britain, perhaps I was wrong. Perhaps it is Theresa May’s very unemotional demeanour that has marked her out as the best possible leader in a time of crisis – someone who, unlike more or less all her rivals and opponents, has not succumbed to the Bremotional turmoil of the last two weeks.

As for me, I’m hoping to get round to writing about the history, science, and politics of anger one day soon…![]()

Follow Thomas Dixon on Twitter: @ThomasDixon2016

Read more about the ‘Living With Feeling Project’

Pingback: What is anger? 1. Martha Nussbaum | The History of Emotions Blog