Jeremy C. Young is an assistant professor of history at Dixie State University (St. George, UT, USA) and the author of The Age of Charisma: Leaders, Followers, and Emotions in American Society, 1870-1940 (Cambridge University Press, 2017). He earned his Ph.D. in United States history at Indiana University in 2013. He is a historian of the 19th and 20th century United States, with particular interests in the history of emotions, social movements, and political communication.

Jeremy C. Young is an assistant professor of history at Dixie State University (St. George, UT, USA) and the author of The Age of Charisma: Leaders, Followers, and Emotions in American Society, 1870-1940 (Cambridge University Press, 2017). He earned his Ph.D. in United States history at Indiana University in 2013. He is a historian of the 19th and 20th century United States, with particular interests in the history of emotions, social movements, and political communication.

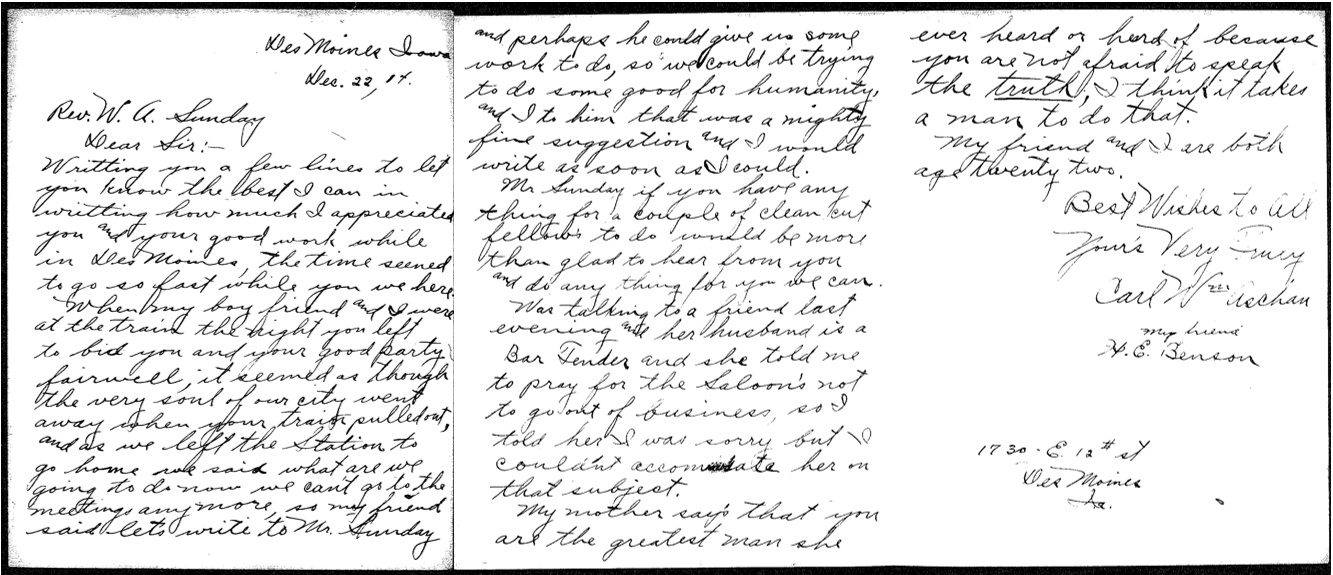

In 1914, twenty-one-year-old Carl William Aschan watched evangelist Billy Sunday’s train depart from Des Moines, Iowa with a sense of spiritual emptiness – “as though the very soul of the city went away.” Dejectedly, Aschan and his friend H. E. Benson wondered aloud, “What are we going to do now we can’t go to the meetings any more[?]” “Let’s write to Mr. Sunday,” Benson suggested, “and perhaps he could give us some work to do, so we could be trying to do some good for humanity.” Aschan put the question to Sunday in a letter. “Mr Sunday if you have any thing for a couple of clean cut fellows to do would be more than glad to hear from you and do any thing for you we can.”[i]

Historians tend to think of emotions as an effect of cultural changes. In many cases, we focus on the emotions that are considered acceptable or desirable within a culture, and we study how those emotional standards change over time.[ii] It’s easy to view Aschan’s anguish over Sunday’s departure as conditioned by a largely Protestant society that privileged religious conversions, leading Aschan and Benson to lament the newfound lack of religious experience in their lives. But what if we instead imagined emotions as a site of agency – as the cause of social and cultural shifts? What if, simply by experiencing the influence of Billy Sunday, Carl William Aschan changed the course of history?

Converts such as Aschan generally expressed their desire to convert in personal terms, as a response to internal emotional crises. Prior to his conversion, schoolteacher Edgar G. Gordon wrote, he had been consumed by self-loathing for his “pool-playing, card-playing, dancing, ‘suds’-sipping” ways. “I had long had a vision of service and of my duty,” he wrote to Sunday in frustration in 1913, “but until you challenged, until you dared me to be a man, I had not the decision [to act upon it].”[iii] Similarly, Charles H. Thurston detailed his struggles with alcoholism prior to his encounter with Sunday. “In spite of all I could do the appetite [for alcohol] held me fast,” he lamented. “This continued for seven or eight years” until a tabernacle conversion finally sobered him up.[iv]

Once they listened to Sunday’s emotional sermons and underwent powerful religious experiences, however, converts often found personal transformations to be inadequate expressions of their newfound selves. Many were like Aschan and Benson, burning up for “any thing for a couple of clean cut fellows to do” – longing for a great collective work that would invest their conversions with an enduring sense of purpose. Many found such a mission in Sunday’s exhortation to convert others. William Ward Ayer, converted by Sunday at the age of nineteen, became a prominent New York minister and converted thousands or his parishioners. “What happened to them,” he explained in 1960, “happened to them because of what happened to me through Billy Sunday.”[v] Syracuse bank president Lucius A. Eddy, another Sunday follower, singlehandedly procured over four thousand converts over a twelve-year period.[vi] Sunday followers who lacked the prominence of Ayer or the wealth of Eddy worked on a smaller scale, founding Billy Sunday Clubs designed to continue the work of conversion. In a letter to Sunday, new convert Jamie Goldsmith confessed that he had not “done very much in trying to save souls” before he went to the revival meetings; now, however, Sunday had “shown me where I stand.”[vii]

When Sunday’s followers were not converting their neighbors, they were enthusiastically promoting the evangelist’s political platform – particularly his support for prohibition legislation. Sunday revivals often doubled as political campaigns for local or state prohibition legislation, and converts’ sheer numbers and depth of commitment made their movement a force to be reckoned with.[viii] Omaha mayor and prohibition opponent James C. Dahlman, responding to a report in the Omaha Bee that Sunday would like nothing better than to “inundate Jim and sweep him out of the city hall,” was so afraid of the Sunday revival in his city that he sang hymns in the front row of the tabernacle, praised Sunday in the press, and provided city facilities for the revivals free of charge.[ix] Similarly, Sunday’s comment to a Columbus, Ohio reporter that mayor George Karb might have been “elected by the whiskey ring” was enough to send Karb skittering to address the tabernacle crowd in that city.[x] Dahlman and Karb were right to fear the political power of Sunday’s movement. In November 1916, Michigan voters passed a statewide ban on alcohol after Sunday preached in support of the bill in three of the state’s largest cities. Similarly, voters in Decatur, Illinois enacted prohibition just months after Sunday had conducted a revival there; journalist Bruce Barton noted that Sunday’s presence had galvanized local churches and converted the city’s most important newspaper to the dry cause.[xi]

Historians should fight the urge to dismiss these activities as conditioned solely by emotional and cultural standards. It’s true that turn-of-the-century Americans, particularly those in the middle class, longed for intense emotional experiences that would ground them in a newly unfamiliar society, and that most converts wanted to find emotional fulfillment, not to drive national policy debates – at least at first.[xii] Yet by attaching themselves to a leader and movement with a definite political platform, many Sunday followers decisively entered the public sphere. Sunday’s movement was only as strong as the number of followers he could muster. Simply by connecting emotionally with Sunday and converting in his tabernacle, converts swelled the ranks of his movement and made him and his causes politically powerful; their desire “to do some good for humanity” under his auspices only augmented their influence. The emotional experiences of Sunday’s followers redirected their internal conflicts toward external political goals and helped them to shape historical trends. By transforming themselves, converts such as Aschan transformed their society as well.

References

[i] Carl William Aschan to Billy Sunday, Dec. 22, 1914, folder 23, box 1 (reel 1), Papers of William and Helen Sunday, Grace College and Theological Seminary, Winona Lake, IN.

[ii] Peter N. Stearns and Carol Z. Stearns, “Emotionology: Clarifying the History of Emotions and Emotional Standards,” American Historical Review, Vol. 90, No. 4 (October 1985), 813, 816, 825.

[iii] Edgar G. Gordon to Billy Sunday, Nov. 16, 1913, folder 42, box 1 (reel 2), Papers of William and Helen Sunday.

[iv] Charles H. Thurston, “From One of the Converts,” in “Personal Gains from the Sunday Campaign: A Sheaf of Testimonies,” The Congregationalist, February 22, 1917, 257.

[v] Interview with William Ward Ayer in The Billy Sunday Story, dir. Irvin S. Yeaworth, Jr. (orig. pub. Chester Springs, Penn.: Sacred Cinema/Westchester Films, ca. 1960; Garland, Tex.: Beacon Video Ministries, 1989).

[vi] Homer Rodeheaver, Twenty Years with Billy Sunday (Winona Lake, IN.: Rodeheaver Hall-Mack, 1936), 125.

[vii] Jamie Biggerstaff Goldsmith to Billy Sunday, 1924, folder 33, box 1 (reel 2), Papers of William and Helen Sunday.

[viii] Rodeheaver, Twenty Years with Billy Sunday, 32.

[ix] Omaha Bee, Oct. 27, 1915, quoted in Leslie R. Valentine, “Evangelist Billy Sunday’s Clean-Up Campaign in Omaha: Local Reaction to His 50-Day Revival, 1915,” Nebraska History, 64 (1983), 222-23.

[x] “Sunday Comes Late Today,” Columbus Citizen, Dec. 28, 1912, 1, quoted in Donald Elden Pitzer, “The Ohio Campaigns of Billy Sunday with Special Emphasis upon the 1913 Columbus Revival” (M.A. thesis, Ohio State University, 1962), 95, 124.

[xi] Bruce Barton, “In the Wake of Billy Sunday,” Home Herald, Vol. 20, No. 22 (June 2, 1909), 4.

[xii] T. J. Jackson Lears, No Place of Grace: Antimodernism and the Transformation of American Culture, 1880-1920 (New York: Pantheon, 1981), 8-11.