Professor Seth Koven of Rutgers University researches and teaches the social, economic and cultural history of Britain and Europe in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. His award-winning book, Slumming: Social and Sexual Politics in Victorian London (Princeton University Press, 2004) analyzed the relationship between eros and altruism in shaping social welfare in modern Britain.

Professor Seth Koven of Rutgers University researches and teaches the social, economic and cultural history of Britain and Europe in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. His award-winning book, Slumming: Social and Sexual Politics in Victorian London (Princeton University Press, 2004) analyzed the relationship between eros and altruism in shaping social welfare in modern Britain.

In Episode 11 of ‘Five Hundred Years of Friendship’ Professor Koven speaks about the unusual friendship between Muriel Lester and Nellie Dowell – the subject of his forthcoming book, The Match Girl and the Heiress (Princeton University Press, 2015). This post for the History of Emotions Blog is an edited extract from the introduction to that book, reproduced here with the kind permission of the publisher.

__________

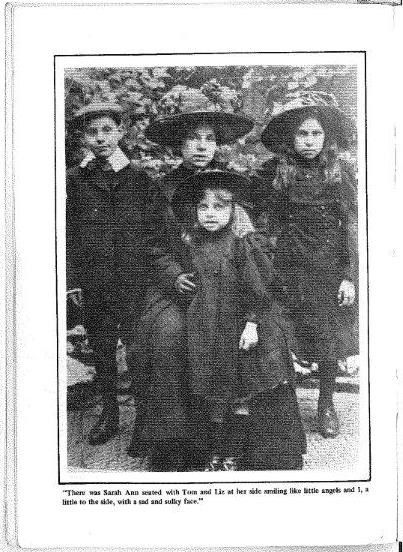

I cannot say with certainty how and when they met, but I do know that Muriel Lester and Nellie Dowell loved one another. That they ever met seems improbable, more the stuff of moralizing fiction than history. Muriel was the cherished daughter of a wealthy Baptist shipbuilder, reared in the virtuous abundance of the Lester family’s gracious Essex homes. A half-orphaned Cockney toiling in the match industry by age twelve, Nellie spent her earliest years in east London’s mean streets and cramped tenements, and her girlhood as a pauper ward of the state confined to poor law hospitals and barrack schools. During the first decades of the twentieth century, they were “loving mates” who shared their fears, cares, and hopes. Their love allowed them to glimpse the possibility of remaking the world according to their own idealistic vision of Christ’s teachings. They claimed social rights, not philanthropic doles, for their slum neighbors. They struggled for peace in war-intoxicated communities grieving for brothers, fathers, and husbands lost to the Western front. Nellie dreamed of ladies’ clean white hands. Muriel yearned to free herself from the burden of wealth. Together, they sought to create a society based on radically egalitarian principles, which knew no divisions based on class, gender, race, and nation.

Muriel Lester in 1938

The Match Girl and the Heiress is about Muriel and Nellie, the worlds of wealth and want into which they were born, the historical forces that brought them together, and the “New Jerusalem” they tried to build in their London slum neighborhood of Bow. Their friendship was one terrain on which they used Christian love to repair their fractured world. The surviving fragments of their relationship disclose an all but forgotten project of radical Christian idealism tempered by an acute pragmatism born of the exigencies of slum life. They explored what it meant to be rights-bearing citizens, not subjects, in a democratic polity. Convinced that even the smallest gestures – downcast eyes or a deferential nod of the head –perpetuated the burdened histories of class, race, and gender oppression, Nellie and Muriel believed that they could begin to unmake and remake these formations – and hence the world — through how they lived their own lives. The local and the global, the everyday and the utopian, the private and the public existed in fruitful tension as distinct but connected realms of thought, action, and feeling.

Their story is part of a much broader impulse among thousands of well-to-do women and men in late-19th and early 20th century Europe and the United States to traverse cultural and class boundaries in seeking “friendship” with the outcast. A few like Muriel self-consciously “unclassed” themselves by entering into voluntary poverty to model a society liberated from the constraints and inequalities of class. Nellie could not afford to “unclass” herself. She lived and died a very poor woman. She, like Muriel, crossed borders into a place of their own making, one committed to the unfinished business of reimagining gender, class and nation by breaking down the hierarchies upholding them.

That place was Kingsley Hall, Britain’s first Christian revolutionary “People’s House” and the institutional incarnation of Nellie and Muriel’s friendship where they tried to translate ideals of fellowship into the stuff of everyday life. Founded in February 1915 in an abandoned hell-fire Zion Baptist chapel amid the furies unleashed by the world at war, it was an outpost of pacifism, feminism, and socialism committed to radical social sharing. Muriel and Kingsley Hall’s original residents established East London’s chapter of the pan-denominational Brethren of the Common Table whose members satisfied their minimal weekly needs for food, shelter, and clothing and then placed whatever excess remained from their earnings on the communion table for others to take. They asked no questions and accepted no thanks. A special London correspondent from the United States witnessed the earnest Brethren in conversation at Kingsley Hall. He gleefully reported that the involuntarily poor among them upbraided their well-born friends for excessive self-denial. “It drives me wild to see these people going short of things they want,” one widowed mother of four complained. “They ain’t used to it. It’s going too far.” At times comically self-serious, residents of Kingsley Hall decided it was too risky to leave fun to chance: they held temperance “Joy Nights” where men and women could laugh, dance and socialize.

My first day at Kingsley Hall Dagenham, I read Nellie’s witty warm letters to Muriel. I was instantly struck by her humor and intellect as well as her evident discomfort with letter writing and the conventions of Standard English. Full of mundane chat, her longing for Muriel, and events so inconsequential that she probably forgot them the next day, Nellie’s letters invite listening to her talk as much as reading what she wrote. They retain the rhythms and freshness of speech as thoughts take flight without regard to formal punctuation. Nellie’s letters baffled, delighted, and intrigued me. Who was Nellie? Why did she write these letters, what did they signify, and why did Muriel save them?

Matchworkers at the Bryant and May factory, 1888 (c) TUC Library Collections

Nellie, I came to learn, had a remarkable global life as a proletarian match factory worker and Cockney cosmopolitan before she met Muriel. When her sailmaker father died at sea in 1881, poverty compelled her devoted mother Harriet Dowell to give her up to Poor Law officials who sent her to late-Victorian Britain’s most controversial Poor Law “barrack” school and orphanage. Nellie entered the match industry in the year of the world famous “Match Girls’ Strike” of 1888. Labor conflicts dogged her everywhere she went. Her arrival in Wellington in June 1900 was fiercely debated in the New Zealand parliament and sparked a political crisis for the Liberal ministry.

Proletarian spinsters don’t have literary executors; their family members rarely enjoy material circumstances to enable them to save letters and papers. If Nellie’s papers do exist, I have not found them. The most important sources about her survived because Muriel preserved them. Nellie and her letters mattered to Muriel. She made no secret of how much she loved, admired, and depended on Nellie, with her “broad commonsense outlook on life,” “staggering generosity” and “genius” for solving problems. In a collection full of missives from major and minor figures in modern history – heads of state, activists and reformers, Nobel laureates – Muriel herself put Nellie’s eleven letters in a manila envelope. In the distinctive unsteady hand of her old age, she wrote “Nell” on it. No other documents in her papers bore such indisputable marks of Muriel’s self-archiving, at least when I first touched and read her papers.

__________

Return to: Five Hundred Years of Friendship at the History of Emotions Blog

Like many of the first women’s college principals, Constance Maynard (Westfield College 1882-1913) found her work all too often unrewarding and lonely. She had refused an offer of marriage soon before starting as principal and she remained unmarried for life. As scholars have noted, her relationships with the women in her college were often fraught; she became involved in love triangles among the staff, and developed troubling relationships with students. In her diaries she often admitted to being deeply unhappy and this, combined with the stresses of managing a college, led to depression and at least two bouts of long-term illness. She countered these conditions with holidays, cycling, vegetarianism, and, most importantly, friendship. It was in letters to her alumnae, whom she saw and addressed as her ‘dear friends’, that she could admit to her feelings of despair and receive the comfort of their support.

Like many of the first women’s college principals, Constance Maynard (Westfield College 1882-1913) found her work all too often unrewarding and lonely. She had refused an offer of marriage soon before starting as principal and she remained unmarried for life. As scholars have noted, her relationships with the women in her college were often fraught; she became involved in love triangles among the staff, and developed troubling relationships with students. In her diaries she often admitted to being deeply unhappy and this, combined with the stresses of managing a college, led to depression and at least two bouts of long-term illness. She countered these conditions with holidays, cycling, vegetarianism, and, most importantly, friendship. It was in letters to her alumnae, whom she saw and addressed as her ‘dear friends’, that she could admit to her feelings of despair and receive the comfort of their support.

Emma Townshend is a writer and journalist, and the author of

Emma Townshend is a writer and journalist, and the author of

Dr Helen Rogers

Dr Helen Rogers

That there are better or higher friendships – different people may call them soul friends, close or old friends, or best friends – as opposed to instrumental and casual friendships, or mere friendliness, is surely right. But to say that great friendship is defined solely by its goodwill seems to miss its essence. Goodwill exists in these best kinds of friendship, but, unlike the lesser types, best friendship – arguably the quintessential sort – is based on something far more profound. In other words, a definitional approach to friendship has its limits.

That there are better or higher friendships – different people may call them soul friends, close or old friends, or best friends – as opposed to instrumental and casual friendships, or mere friendliness, is surely right. But to say that great friendship is defined solely by its goodwill seems to miss its essence. Goodwill exists in these best kinds of friendship, but, unlike the lesser types, best friendship – arguably the quintessential sort – is based on something far more profound. In other words, a definitional approach to friendship has its limits.