As part of #shameweek, I want to sketch a theory of shame’s crucial place in liberalism and in critiques of liberalism.

Secular liberalism, which was born in Athens in the fifth century BC, replaced the gods of Olympus with the god of Public Opinion. According to the fifth century philosopher Protagoras, who is perhaps the father of liberal philosophy, what drives us to obey the law and fit in with the manners of civilisation, is not fear of divine punishment, but rather our natural sense of shame and justice. These are the sentiments that enable us to live together in cities. Shame and the desire for public approval are the bedrock of liberal civilisation.

Secular liberalism, which was born in Athens in the fifth century BC, replaced the gods of Olympus with the god of Public Opinion. According to the fifth century philosopher Protagoras, who is perhaps the father of liberal philosophy, what drives us to obey the law and fit in with the manners of civilisation, is not fear of divine punishment, but rather our natural sense of shame and justice. These are the sentiments that enable us to live together in cities. Shame and the desire for public approval are the bedrock of liberal civilisation.

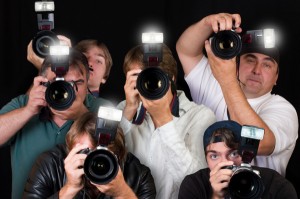

What really matters to humans, according to Protagoras, is not what the gods think of us (who knows if the gods really exist or not) but what other people think of us. ‘Man is the measure of all things’, he claimed, therefore the measure of our true worth is our public standing. This radical idea, which is the kernel of liberalism, introduces a new volatility and insecurity into public life. The old caste divisions are less certain, more fluid. To rise to the top of society, all one needs are the rhetorical and PR skills to win the attention and the approval of the public, and to avoid their censure. One’s ascent could be swift, but so could one’s fall.

Cicero, for example, manages to rise into the senate class of the Roman Republic on the wind of his rhetorical ability, and his ability to network, win friends and influence people. He is the archetypal liberal, deeply driven by the desire for public approval, and at the same time, wracked with the fear of making a fool of himself in front of the public (we hear a description of how Cicero suffered what sounds like a panic attack once when giving a major speech, and he says in De Oratore that the better the orator, the more terrified he is of public speaking).

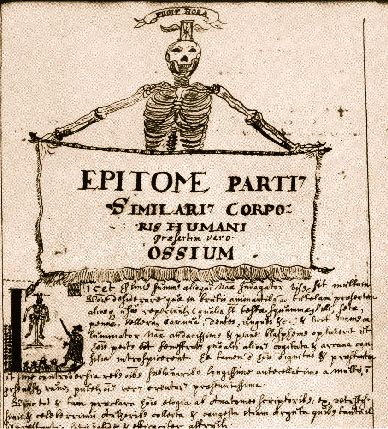

It is interesting, in this respect, that the first recorded instance of social anxiety is during the Athenian enlightenment, at the birth of liberalism, at the very moment when the public is being deified into an all-powerful god. We read in Hippocrates of a man who ‘through bashfulness, suspicion, and timorousness, will not be seen abroad; loves darkness as life and cannot endure the light or to sit in lightsome places; his hat still in his eyes, he will neither see, nor be seen by his good will. He dare not come in company for fear he should be misused, disgraced, overshoot himself in gesture or speeches, or be sick; he thinks every man observes him’. There is, I suggest, a profound connection between liberalism’s deification of public opinion and the terror of making a fool of oneself in public.

Later theorists of liberalism built their ethics on the same natural foundation of our desire for status and our fear of shame and humiliation. Adam Smith, in particular, built his Theory of Moral Sentiments on this idea that humans’ over-riding drive is to look good to others, and to avoid looking bad. We imagine how our actions look to an ‘impartial spectator’, we internalise this spectator, and conduct our lives permanently in its gaze – and that’s what keeps us honest, polite and industrious. We constantly perform to an audience – in fact, his ethics are full of examples taken from the theatre. He constantly asks himself what looks good on the stage, what wins applause. Morality has become a theatrical performance.

It’s a similar ethics as one finds in Joseph Addison’s Spectator and Tatler essays, where he imagines a ‘court of honour‘ that judges the behaviour of various urbanites: this person snubbed me in the street, that person behaved abominably in the coffee-house, and so on. The All-Seeing God is replaced by the thousand-eyed Argus of the Public, which spies into every part of your behaviour, judges you, and then gossips. Unsurprising, then, that Mr Spectator himself should be a shy, self-conscious, retiring character – we long to observe the foibles of others, yet are frightened of our own foibles being found out.

This liberal, Whiggish ethics celebrates the city, because the city is where we are most watched, most commented upon, and therefore where we are most moral. The city makes us polite (from the Greek polis) and urbane (from the Latin urbs). It polishes off our rustic edges and makes us well-mannered. Liberal ethics also celebrates commerce and finance, for the same reason. The man of business must carefully protect their reputation, because his financial standing, his credit, depends on the opinion others have of him. Therefore, commerce makes us behave ourselves. This theory, popular in the 18th century, is tied to the development of the international credit markets – governments have to behave themselves now because they need to maintain the approval of investors (this is well-explored in Hirschman’s The Passion and the Interests).

We can still see this liberal ethics of status and shame today, particularly in the neo-liberalism of the last few decades. It was believed that countries and companies are kept honest by ‘market discipline’ – by the gaze of shareholders and investors. If a finance minister or a CEO behaves badly or shamefully, if they fail to govern themselves or to apply fiscal discipline, they will be punished by the market. Likewise, our culture is ever-more dedicated to seeking the approval of that god, Public Opinion, whose attention we seek through blogs, tweets, YouTube videos, reality TV shows, through any publicity stunt we can keep up. The greater your public following, the greater your power.

Yet, right at the very birth of liberalism in the fifth century BC, a critique of it arose, also based on shame.

Plato insisted that liberal democratic societies had produced a false morality, a morality of spectacle. We only care about looking good to others, rather than actually being good. He illustrated this with the myth of the ring of Gyges, which makes its wearers invisible. If we had that ring, and were protected from the gaze of others, would we still behave ourselves, or would we let ourselves commit every crime imaginable? If all that is keeping us honest is the gaze of other people, then what really matters is keeping your sins hidden from the public.

Civilisation, Plato suggested, had made us alienated, which literally means ‘sold into slavery’. We have become slaves to Public Opinion, before which we cringe and tremble like a servant afraid of being beaten. We contort ourselves to fit the Public’s expectations, no matter how much internal suffering and misery it causes us. It’s far more important to look good to the Public than to actually be happy and at peace within. So we put all our energy into tending our civilised masks, our brands, our shop-fronts, while our inner selves go rotten.

One finds a similar critique in the Cynics and the Stoics, both of whom lambast their contemporaries for being pathetic slaves to public opinion, who tremble at the prospect of advancement or being snubbed. A man of virtue, they insist, cares only for whether they are doing the right thing, they don’t care how that looks to the public, how it plays on the evening news. Against the spin and sophistry of liberalism, they put the steadiness and self-reliance of virtue.

Diogenes the Cynic, attacking shame

The Cynic takes the revolt against liberal morality to an extreme. It’s a hypocritical morality, the Cynic insists, that divides our public from our private selves, and which makes us hide behaviour that is in fact perfectly natural. The Cynic breaks down the wall between the public and the private self. Anything which one is happy to do in private – such as defecation, say, or farting, or masturbation – one should be equally happy to do in public. Cynics trained themselves to de-sensitise themselves to public ridicule, not just for the hell of it, but so that they could move from a false ethics based on looking good to others, to a true ethics based on obedience to one’s own ethical principles.

Today, perhaps, we are more than ever obsessed with our public standing, and terrified of public ridicule. As Theodore Zeldin wrote: ‘Creating a false impression is the modern nightmare. Reputation is the modern purgatory.’ We live, as Rousseau put it, ever outside of ourselves, in the opinions of others (this, in fact, is the meaning of paranoia – existing outside of oneself). This desperate need for public approval, and terror of shame or obscurity, is, I would suggest, at the heart of many of the discontents of liberal civilisation – social anxiety, depression, narcissism.

Yet we don’t have to accept these discontents as an inevitable part of civilisation, as Sigmund Freud or Norbert Elias argued. We can in fact modulate shame. We can reprogramme shame by reprogramming the attitudes and beliefs which direct it. As Plato, the Stoics and the Cynics suggested, we can challenge the values that give so much importance to status and reputation, and learn to embrace new values, which focus less on public opinion, and more on being true to our own principles. Many of the Greeks’ techniques for cognitive change are found in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy today – including a technique specifically designed to help people overcome a crippling sense of shame or self-consciousness. It’s called ‘shame-attacking‘, and involves intentionally drawing attention and ridicule to yourself in order to de-sensitise yourself to the experience, just as the Cynics did 2400 years ago.

Which emotion links some people’s attitudes to the banking bonuses, journalists hacking the voicemail of Milly Dowler’s parents, our reaction to eating bitter lemons, the smell of Hydrogen Sulphate, and the Holocaust? The answer is disgust.

Which emotion links some people’s attitudes to the banking bonuses, journalists hacking the voicemail of Milly Dowler’s parents, our reaction to eating bitter lemons, the smell of Hydrogen Sulphate, and the Holocaust? The answer is disgust. Over at the New York Times’ excellent Opinionator blog

Over at the New York Times’ excellent Opinionator blog This may sound like science fiction, but many young neuroscientists are already researching morality pills, including

This may sound like science fiction, but many young neuroscientists are already researching morality pills, including