Is it taboo for academics to talk about their spiritual experiences? What can the humanities bring to the study of such experiences? Can we steer between the Scylla of religious dogmatism and the Charybidis of materialist reductionism when interpreting such experiences? I interviewed Jeff Kripal, professor of philosophy and religious thought at Rice University, and one of the more entertaining, brave and unusual voices in religious studies and the humanities in general.

Is it taboo for academics to talk about their spiritual experiences? What can the humanities bring to the study of such experiences? Can we steer between the Scylla of religious dogmatism and the Charybidis of materialist reductionism when interpreting such experiences? I interviewed Jeff Kripal, professor of philosophy and religious thought at Rice University, and one of the more entertaining, brave and unusual voices in religious studies and the humanities in general.

Jeff, your mentor, Wendy Doniger, has just had her book The Hindus pulped by Penguin India, after a nationalist campaign against it. This must give you deja-vu back to 1995, when your first book, Kali’s Child, provoked a similar shit-storm, even leading to debates in the Indian parliament over whether it should be banned, because of its suggestion that the mysticism of Ramakrishna was connected to his possible homosexuality. You were 33, it was your dissertation, it must have been unpleasant.

Yes. The book got me into a huge amount of trouble, and I’m still in trouble. It was awful and scary. The hate was over the top. The book itself is deeply appreciative and warm and sensitive about Hindu culture. It’s just that it tackles ideas that haven’t reached a tipping point yet in India.

Did people think you were being reductive? Because it seems to me you were suggesting Ramakrishna’s mysticism was both sexual and spiritual.

The people who drove the campaign were mainly engineers and scientists. And when I explained my argument that it was mystical and sexual at the same time, it just fried all their circuits. They think of things in very binary terms. Everything has to mean one thing, it has to be very clear.

The people who drove the campaign were mainly engineers and scientists. And when I explained my argument that it was mystical and sexual at the same time, it just fried all their circuits. They think of things in very binary terms. Everything has to mean one thing, it has to be very clear.

In subsequent books, you’ve returned to that point, about the close relationship between the erotic and the mystical. That seems to be an uncontroversial point – look at Plato, for example, or charismatic Christianity, where encounters with the Holy Spirit often sound pretty much like orgasms.

Right. One of the things I wanted to do in my second book, Roads of Excess, Palaces of Wisdom (2001), was show that my ideas about sex and mysticism were not just applicable to a single Indian saint in the 19th century, but that actually they work across the board, in western culture as well.

In Roads of Excess, you look at various western academics who wrote about mysticism, including Evelyn Underhill and Elliot Wolfson, and argued that they had mystic experiences themselves, but didn’t talk about them. They kept them secret.

Yes, and I think one of the reasons they kept them secret was their mystical experiences were connected to their sexuality.

In that book you ‘came out’, as it were, about your own spiritual-erotic experiences. Could you tell us about the spiritual experience you talk about in Roads?

I was living in Calcutta in 1989. In late October and early November, I was engaging in Kali Puja rituals, which to any western eye seem like a combination of Halloween and a religious celebration. The imagery is very macabre, and its a profound beautiful event that goes on for days. I had been visiting these temples all day, and went to bed late.

I was living in Calcutta in 1989. In late October and early November, I was engaging in Kali Puja rituals, which to any western eye seem like a combination of Halloween and a religious celebration. The imagery is very macabre, and its a profound beautiful event that goes on for days. I had been visiting these temples all day, and went to bed late.

Sometime early in the morning, I woke up, but my body didn’t. My body was paralysed but my mind came on line. Classic sleep paralysis experience. Then this presence came into the room, or out of me, or something – I don’t know where the fuck it came out of – but it was on top of me, and it was engaging me sexually. But in a really scary way. I thought I was dying. My first thought was I was having a heart attack or being electrocuted. Because it felt like I imagine it feels like when you stick a fork in the wall-socket. My whole body was vibrating. But it was also intensely erotic, to the point where it got so intense it propelled me out of my body – I had a classic out of body experience where I was floating in the room. I eventually got back into my body and woke up. But I felt residual energies in me – the feeling was that something was planted or downloaded in me. It wasn’t just blind energy, it was noetic – it had a philosophical content to it which I couldn’t have articulated at the time. All the books since have been trying to get that out on the page. It wasn’t a revelation event. It was a transmission event, which sent me off looking for similar events in texts and other people’s experience.

It reminds me of Philip K. Dick’s strange Valis experience, and how it wasn’t clear or certain to him what he meant. He spent eight years trying to figure out what it was.

This is what attracted me to his writing. When I read him, I recognized the experience, although his experience went on for weeks and months. I could see in Dick’s Valis event, the feel of what I had known. I suppose an emotion is some sort of intellectually coded energy.

You suggest unusual experiences like that are both culturally constructed – shaped by the culture you’re immersed in – but also not just culturally constructed.

I think particular cultural contexts allow them and catalyse them. I wouldn’t have had that particular experience without the Kali Puja going on around me. But I don’t think the Kali Puja caused it. I think it allowed it and catalysed it. Cultural context shapes, mediates and expresses the phenomenological feel of these events. But it’s not producing them. I think they’re cross-cultural. They’re not even historical – they’re not located on a particular point in space-time. But when they interact with human beings, they are. Philip K. Dick said he heard a voice in a dream, which said ‘someday the mask will come off, and you will realize the truth as it really is’. Dick says: ‘the mask came off, and I realized, I was the mask’. That’s the sort of flip I’m talking of – anything that happens to Jules and Jeff will become ‘us’, because we’re the mask.

In Mutants and Mystics (2011), you looked at how superhero comics and sci-fi helped to shape new forms of spiritual experience in the 20th century, including alien abduction experiences. You suggest science fiction and ‘marvellous tales’ became a way for people to connect with the paranormal and the mystic in an ostensibly rationalised and disenchanted culture. Is the field of Religious Studies beginning to take the paranormal more seriously?

In Mutants and Mystics (2011), you looked at how superhero comics and sci-fi helped to shape new forms of spiritual experience in the 20th century, including alien abduction experiences. You suggest science fiction and ‘marvellous tales’ became a way for people to connect with the paranormal and the mystic in an ostensibly rationalised and disenchanted culture. Is the field of Religious Studies beginning to take the paranormal more seriously?

I think so. You’re seeing a mini-renaissance on that. This is the origins of the field. The field of psychical research was central to people like William James, and Carl Jung, and Freud to some extent, and to Andrew Lang. Our fore-fathers or founders all began here. And then we pushed it off the academic table over the last 100 years. What I’m trying to say is, let’s put it back, not because that’s what religion is about, but because when we put it back on the table, all the other stuff looks slightly different. When people talk about the paranormal, it’s behind what we used to call magic, what we used to call myth, what we used to call mysticism – it’s fricking everywhere.

In Authors of the Impossible (2010),you talk about writing and creative inspiration as a paranormal act – a sort of co-creation between the imaginer and the Imaginal.

Yes. One of the conclusions of the humanities is that we’re written. And one of the things we’re most written by is culture and religion. If you talk to people who have these paranormal experiences, they say are things like ‘it was as if I was a character in a novel’, or ‘it was as if I was inside a movie’. I think they are. I think we are too, right now. We’re written, composed by our ancestors.

What shocked me was how many textual allusions people would naturally use to describe a paranormal event. They would talk about puns, jokes, allusions, readings or messages. It’s a textual process going on in the physical environment.

A paranormal event becomes an invitation to re-write the script. That could be on a personal level, or a cultural level for writers and film-makers. Take writers like Philip K. Dick or Whitley Strieber – these are people who create fantasy for a living. They know their spiritual experiences are fantastic. They know they’re being mediated by their imagination. They’re not taking them literally. And yet they would insist that something very real is coming through. That’s what drew me to them – I don’t find that in a lot of religious people. They confuse the stained glass window with the light coming through.

You mean that with fantasy or sci-fi writers like Dick and Strieber, there’s a playfulness or sense of co-creation?

Exactly.

The idea of the imagination as a sort of generator of spiritual realities reminds me of the Romantic-transcendentalist idea that creative minds are the legislators of the world. You have a similar idea with the Inklings – Tolkien, Lewis, Barfield – and their idea of stories and the imagination co-creating reality with God.

There are all kinds of older precedents too – the idea of Christ as the logos, the Kabbalistic notion of reality being composed of Hebrew letters. There are all these intuitions about this.

Zhivago seeing Lara from a tram – an uncanny coincidence

You talk a lot about uncanny coincidences, which reminds me of something novels do for us – they affect our emotions by creating certain uncanny moments when characters’ paths cross again through some weird coincidence. Like in Dr Zhivago when the hero happens to see his long-lost love after decades apart, or War and Peace when the injured Andre Volkonsky happens to find himself in a surgeon’s tent next to his greatest enemy Anatole Kuragin, and thinks ‘this man is somehow closely and painfully connected to me’. Perhaps that’s one of the reason we love novels – because they give us that sense of an aesthetic pattern to life. Milan Kundera talks about this in the Unbearable Lightness of Being:

Without realizing it, the individual composes his life according to the laws of beauty even in times of greatest distress. It is wrong then, to chide the novel for being fascinated by mysterious coincidences, but it is right to chide man for being blind to such coincidences in his daily life. For he thereby deprives his life of a dimension of beauty.

Right. Synchronicity is a flash moment where you’re glimpsing a hidden structure or web of connections. But these can also be little hints that, yes, I am caught in a novel. That can be reassuring or disturbing, depending if you like the novel or not.

You clearly have a real sense of the power of books and reading. Reading a book can be like a seance, connecting you to the dead. It can be a portal into another dimension. Your books give a sense of reading as something potentially dangerous.

I hope so. That’s the intention for sure.

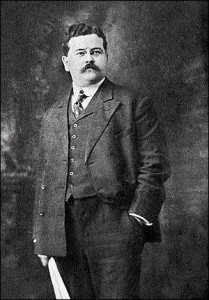

One of the things you get across is the complete uncertainty of religious experience – we can’t be sure what’s out there. I think of your chapter on Charles Fort in Authors of the Impossible, and all the theories he put forward about what’s happening with religious experiences – that there’s some massive Solaris-type consciousness playing games with us, or possibly there are innumerable spiritual entities around us, some of which are trying to eat us!

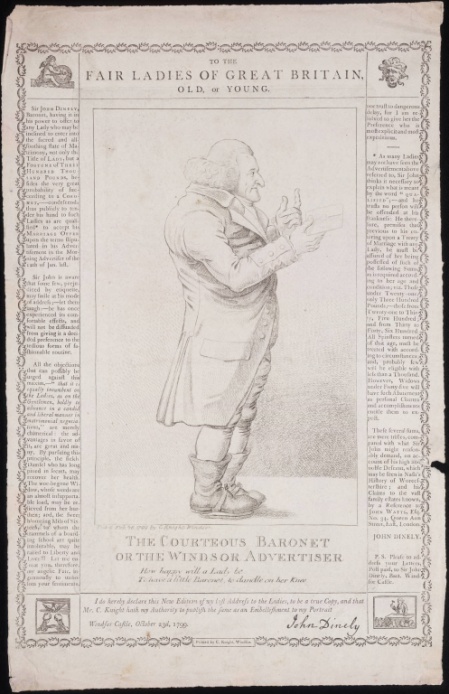

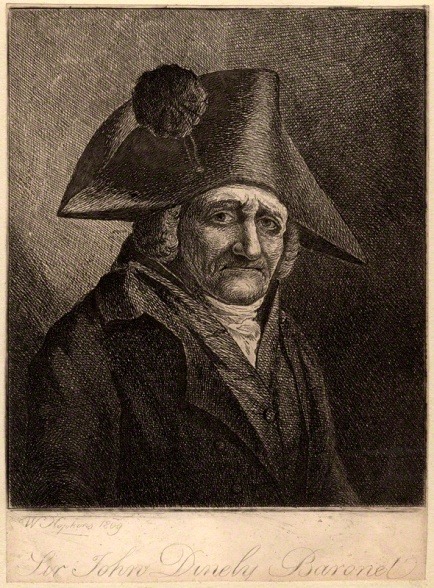

Charles Fort, chronicler of the marvellous, creator of the Fortean Times

Right – some might be trying to feed on our emotions. I love Charles Fort. He was a bold thinker. He emphasized the silliness or the trickster dimension of a lot of this. That’s important. The way this stuff seems to be playing with us, it has a kind of playful quality.

A skeptic might say, OK, these experiences seem very much tied up with our imaginations, very much tied up with our cultural expectations. Does that not suggest it’s just our imagination.

The problem with that is we lack a sufficiently robust theory of the imagination. The skeptic means the imagined is simply the imaginary. I would say often it is. But what you get in these moments is a double sensibility – the visionary knows what he or she is seeing is imagined, but also that it pertains to something that is not imagined. Sometimes that’s symbolic, but sometimes it’s empirical.

For example, Mark Twain dreams about his brother’s funeral. It’s really detailed. Two weeks later his brother dies in an explosion, and the funeral is exactly what he had seen in his dream. There you have an imagined event that corresponds perfectly to an event in space-time. So you have to say, the imagination is acting as a super-sensory organ cognizing something two weeks down the space-time continuum.

You write about the Society for Psychical Research in the 1890s, and how it tried to build an empirical evidence base for the paranormal. You prefer a more anecdotal approach – telling stories playfully, where the reader is never sure if you’re being serious or not. They’re marvelous stories. But they won’t convince the skeptic.

No, it will never convince the skeptic because the skeptic is really a materialist debunker. And here’s the other problem. A lot of the skeptical strategies are along these lines – you show us a robust paranormal event in a laboratory and we will believe you. The problem is, that demand is ignorant of how paranormal phenomena normally arise, which is in moments of trauma, death, illness or accident.

Or sex.

None of which you can get in a laboratory. So setting up the test like that is like saying, you prove that there are stars in the sky, but you can only do that during the day.

But a medium should be able to do their thing in a laboratory as well. Myers thought paranormal phenomena would be open to that sort of scientific inquiry and a convincing evidence base would arise. That doesn’t seem to have happened.

I think any reasonable person who reads up on the paranormal literature will be convinced they established something. But it’s difficult to say what, because the phenomena are not objects. They’re always stories that someone is telling you. It’s a different kind of data set. This is why one of my arguments is that the study of these phenomena should be done by the humanities.

Some scientists are still trying to build up the evidence base, aren’t they, like Dean Radin or Rupert Sheldrake.

Yes, and I admire their work. They are getting evidence but it’s not the UFO landing on the White House lawn that people are asking for. I don’t think that will happen because I don’t think that’s what these phenomena are. Ultimately I think it’s us. We’re the ones doing this. I don’t mean Jules and Jeff, I mean something weirder coming through us. But it’s not an object, it’s a subject.

OK. Many of the spiritual visionaries you’ve written about tried to find a middle-ground in their approach to spiritual experiences, between the dogmatism of organized religion and the dogmatism of scientific materialism. You’ve maintained that position yourself, outside of any organized religion. Indeed, you’ve written a book about Esalen, the commune in California that helped to create the New Age, a new ‘religion of no religion’.

OK. Many of the spiritual visionaries you’ve written about tried to find a middle-ground in their approach to spiritual experiences, between the dogmatism of organized religion and the dogmatism of scientific materialism. You’ve maintained that position yourself, outside of any organized religion. Indeed, you’ve written a book about Esalen, the commune in California that helped to create the New Age, a new ‘religion of no religion’.

Indeed.

I personally have recently joined the Christian tradition, with full acceptance that people can reach God through other traditions, because, firstly, I think religious traditions have a practical idea of ethics – which helps to protect you from the darkness outside you and inside you. As Charles Fort pointed out, how do we know what is out there and whether it wishes us good or ill? I think religious tradition and community is one way to protect yourself (though it doesn’t always work).

There’s also the idea of an ethics beyond the self – I’m not sure how often the New Age goes beyond the Self. I think there’s sometimes a risk of Gnostic hubris there: rather than worship God, people want to become gods or superheroes. What I like about Christianity is the emphasis on brokenness and humility – it’s focused on the god who cries, the god who dies.

A third reason is that older religious traditions provide community structures for all levels of society including the poorest, while with the New Age it’s often more that you pay to go on a course in massage or holotropic breathing or Tarot, then carry on your lonely journey to self-actualization. It’s more individualistic and capitalistic. And the final reason to join the Christian tradition, for me personally, is that my imagination is so grown out of Christian culture.

Right. It’s your mask. Listen, I think there are lot of responses to the situation we’re in that are entirely honourable and have a lot of integrity. And I think sticking within a religious tradition while adopting a pluralist openness to other traditions is a perfectly good way to go. And most people will probably continue to go that way. I come out of a Benedictine education and I sometimes think all my work is just a heretical Christology. It’s about Jesus still.

Having said that, I don’t buy the critique of the New Age / Spiritual-but-not-religious as not ethical or socially engaged. I see the opposite actually. The individuals I have come to know intimately who led those movements all left Christianity or Judaism not out of some superficial pride, but because they were deeply wounded by the tradition, usually around issues of gender or sexuality, so they had to leave to maintain their own physical and moral health. The other reason they left was out of intellectual honesty. They just couldn’t believe anymore – science dissolved their old world-views. They were just being honest. They moved into the human potential movement for really deep and honest reasons, and also to help create a new world, which does not yet exist. It’s sort of like, what would it be like to be a Christian in the first century?

Do you think the US is moving towards an Esalen-like religious culture?

I think the younger generations are. There’s still a lot of superficiality there. A lot of the SBNR folk, it’s a kind of fall-back position. But we know from the polls that the majority of people under 30 describe themselves that way. The big question is whether that holds into their 40s. You’re right that churches and synagogues provide the stability when people have children and want stability and something more black-and-white.

I think the younger generations are. There’s still a lot of superficiality there. A lot of the SBNR folk, it’s a kind of fall-back position. But we know from the polls that the majority of people under 30 describe themselves that way. The big question is whether that holds into their 40s. You’re right that churches and synagogues provide the stability when people have children and want stability and something more black-and-white.

My goal is not to make everyone like me. I’m trying to describe the religious crisis we’re in by virtue of religious pluralism. I want to take people’s religious experience seriously no matter whether they’re seeing Jesus or being abducted by an alien. I don’t see any criteria to reject one and not the other.

There was a piece about the rise of New Atheism in the New Yorker by Adam Gopnik, and he divides Americans into supernaturalists who believe in some sort of God, versus self-makers, who think we create ourselves. You strike me as a supernatural self-maker.

I know, there it is again! No matter what binary you put on the table I’ll be in the middle of it.

But what does that mean, becoming the author of ourselves? It sounds a bit like lucid dreaming.

The reason I’m a supernaturalist in Gopnik’s terms is I don’t think we can manufacture these events. They’re given to us. They’re moments of grace and revelation. Our choice is whether to interact with them or not. To use your language, these are co-creations, between another form of mind or consciousness – which I’m happy to call God – and our own little psyches or masks. I would insist that in many of these cases it’s both supernatural and self-authored.

But explain your idea of waking up, no longer being written but being a more conscious author. In Jewish, Christian or Muslim culture, there’s this idea we’re taking dictation from God or his angels. In that sense we’re being written. But you’re saying we need to wake up and author ourselves?

Part of the problem is a historical one. With the traditional religions, we’re weighed down by scriptural texts written thousands of years ago, which reflect the culture and values of those times.

So we’re stuck in a 2000-year-old story?

Yeah. And it doesn’t work for us anymore. Because we have different moral values and know more about the physical universe.

But there have been so many Christian stories told since then, from Wesley’s electric boogaloo spirituality, to CS Lewis’ multiple worlds science fiction. There have been a series of creative improvisations on some traditional standards, and that’s still going on.

Well, I think they’re really writing new stories, and that’s OK, I’m not a critic of that.

OK, last question, how do academics get to work at Esalen?!

Academics can become work scholars, they can just sign up and go. It involves living for a month, working every day, doing Gestalt work in the day-time and taking the course at night. It’s a total immersion over a four-week period, and it’s relatively reasonable, it’s like $1100 bucks.

Academics can become work scholars, they can just sign up and go. It involves living for a month, working every day, doing Gestalt work in the day-time and taking the course at night. It’s a total immersion over a four-week period, and it’s relatively reasonable, it’s like $1100 bucks.

Kripal’s next book, Comparing Religions: Coming To Terms, has just come out in the UK.

Dr Sally Holloway

Dr Sally Holloway