Dr Hera Cook is an historian of emotions and sexuality at the University of Otago, Wellington, with current interests in emotional management and inequality. Here she reviews William Reddy’s new book for the History of Emotions Blog.

Dr Hera Cook is an historian of emotions and sexuality at the University of Otago, Wellington, with current interests in emotional management and inequality. Here she reviews William Reddy’s new book for the History of Emotions Blog.

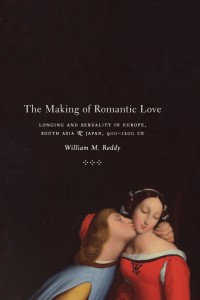

William Reddy is a historian whose work is notable for interdisciplinary depth and an accompanying adventurousness. I have learned a lot from his work and I admire these qualities, which are evident in The Making of Romantic Love. Longing and Sexuality in Europe, South Asia & Japan, 900-1200 CE. The book uses three case studies to illustrate the claim that “sexual desire is not universal” (34). The culture of Medieval French troubadours has traditionally been supposed to provide origins of romantic love in “Western culture.” Reddy compares that sexual culture with two other elite cultures that existed during a similar period; Bengal and Orissa in what is now India and Heian Japan.

Over the past fifteen years, Reddy has engaged with the anthropological literature on emotion, as well as publishing extensively on the application of cognitive and affective neuroscience to definitions of emotion and the use of these ideas in relation to historical evidence. Many neuro-philosophers and neuroscientists argue that “all emotions are associated with activated thought “materials,” that is with cognitions, and emotions are, in practice, indistinguishable from aspects of cognitive processing” (7). Reddy took this conception of emotions as cognition and developed the concept of ‘emotives,’ which are performative speech utterances such as ‘I love you’ or ‘I hate you’. The individual is enabled to discover what they feel through the process of shaping their complex internal experiences into a specific utterance (Reddy, 1997, 2001). Reddy expands this to encompass insights from cognitive behavioral therapy, according to which a person’s emotional temperament consists of an array of “chronically accessible thought material, developed over a lifetime of patterned repetitions and habituations” (7, 371-73).

These ideas provide him with the basis for an approach to romantic or sexual love that is free of what he describes as “Western-specific notions,” such as “passion,” “appetite” or “drive” (6).

The book begins with the statement: “In a common Western way of feeling, romantic love is paired with sexual desire. The lover feels both at once, yet the two feelings are in tension with each other” (1). This recourse to a taken-for-granted “Western” cultural unity is problematic as sexual beliefs vary considerably across heterogeneous populations even within countries. Two decades of research into sexuality in British society suggests to me that romantic love is no longer perceived to be in tension with sexual desire, if it ever was so outside strongly religiously engaged sectors of society. In most of the book, it is the “commonsense Western notion of sexual desire” or appetite that is central and this, I would agree, is central to our conception of sexuality (106).

Reddy defines romantic or sexual love as a “longing for association.” He prefers the term longing because, he claims, “desire has been used as a “synonym for lust, meaning appetitive cravings for sexual release, and because of love’s opposition to lust.” He chose association as “a general term that can refer to any significant relationship” (6). This definition of romantic or sexual love, raises the question; what is the role of the body and specifically the genitals in the experience of “longing for association”?

Rejection of any role in ‘emotion’ for body parts or systems other than the brain, or for the purpose of signaling emotion (blushing, gestures, etc) to others has been an important part of Reddy’s methodology in his previous emotions research. As explained above, he argues that “emotions are, in practice, indistinguishable from aspects of cognitive processing” (7). Hence, any role for the rest of the body is excluded from the “longing for association.” Reddy rarely makes this rejection of bodies explicit, rather he subsumes physical bodies and their functions in the concept of appetite or desire, and any mention of involvement of the body in sexual love is treated as a cultural construction. He believes that “the presumption …sexual desire [is] a powerful bodily appetite” is likely to fade from view as have other “emotional states that were considered extremely common,” giving hysteria and acedia as examples (16). He goes on to explain that “present-day experimental evidence [on sexuality] offers little support for the age-old Western doctrine that there is a sexual appetite that is comparable to hunger or thirst” (16, see also 10). This rejection of the link between sexual desire and what he sees as the uncomplicated appetite of hunger highlights Reddy’s lack of attention to bodies; what of anorexia, bulimia and rising levels of extreme obesity? Any and all of our bodily processes are subject to shaping by culture. There is no category of culturally unmediated bodily appetites from which to withdraw sexual desire. As this suggests, Reddy rejects the existing concept of sexual appetite without providing an answer to questions as to how brain and body do interact to produce action. And the result of Reddy’s rejection of the role of the body in sexual attraction is a term that could apply to any strong affective relationship.

Reddy uses “longing for association” as a basis to compare the medieval French elite conception of romantic love with that in parts of South Asia (Bengal and Orissa) around the twelfth century and with the imperial elite in Heian Japan. The claim that the Western cultural conception of embodied sexual responses differs from those of entirely separate cultures seems incontestable – how could it be otherwise? It is, however, difficult to assess the differences on the basis of the account the book offers. The South Asian evidence largely refers to a single sect, notwithstanding the fact, which Reddy explains, that Vaishnavism and related cults or practices sat within a context of many Indian cults. Did people inhabit a culture of only one sect or did they move from sect to sect according to their needs? What relevance did the beliefs of this sect have to this society? The Devidasis, or temple women, who are described interacting with males were a form of courtesan or geisha who lived outside the mainstream of their society. There were apparently middling groups or castes who rejected the sexual attitudes of this cult but there is no description of the impact of this in what was a highly stratified society. The Japanese evidence consists of poetry and narratives written by elite men and women. It is considerably more detailed than the South Asian sources and closer to the type of material available from France.

In the south of France, the tenth to twelfth century is believed to have seen rapid changes in sexual mores, as a result of the Gregorian Reforms. The reforms included the rejection of clerical marriage and the imposition of life-long marital monogamy on the elite, accompanied by insistence that “all sexual behaviour, all sexual longing, all sexual pleasure was bound up with the realm of sin and profoundly dangerous to the soul” (106). In the tenth century, these ideas, which came from the church fathers, had little purchase. By the late twelfth century, re-marriage due to annulment was much less available, excluding the children of serial sexual relationships from inheritance and their mothers from a secure position. This severely diminished the possibilities available to those rare elite women who were sufficiently beautiful, clever and manipulative to move from partner to partner at the highest levels of the French courts and to their would-be partners. Reddy argues that in response to these Gregorian reform induced changes, romantic love was constructed by the troubadours as fin’amors, a pure and powerful motivating force that could bring sexual partners together in “innocent bliss” free of lust (32). This provides the basis for the long-standing claim that medieval French troubadours created the concept of romantic love, which allegedly continues to shape “longing for association” in “Western culture” today.

There appears to be sufficient evidence to make a comparison between Japan and France, though that for South Asia is more limited. Reddy’s focus is, however, almost wholly on the responses that are analogous to fin’amor and part of his scheme of cognitive emotion, while the embodied experience that the Troubadours and the Church denigrated as lust is reduced to the concept of appetite. He argues that the elites in Bengal and Orissa and Heian Japan had “quite different category schemes for understanding what Christians divided into “bodily” and “spiritual,… [they] simply did not distinguish “appetites” from other types of motivational forces, nor did they group the sexual appetite with hunger or thirst” (5). So how did they treat the embodied element in sexual love? I came away from the book without convincing answers. Reddy commented about Japan and South Asia that “there is no indication in the documents that members of these elites regarded sexual release as inherently pleasurable.” (5). I am unsure what Reddy means by sexual release – the conception of orgasm as release of tension may well be a cultural construction but “sexual release” is a Western cultural euphemism or synonym for orgasm and he appears to be implying that there is no evidence these elites regarded sexual orgasm as pleasurable. This is not credible. Reddy does not explain the construction of embodied experience because he does not believe it is part of the category of emotion. The extent to which readers share this belief may well determine the extent to which they find the book convincing. The book does, however, ask the reader to take a comparative perspective seriously. Reddy’s effort to look beyond his discipline and his cultural framework makes for a challenging and at times rewarding reading experience.

Return to the Introduction to the William Reddy Round-table

Read Katherine Clark’s review.

Read David Lederer’s review.

Read William Reddy’s response.