Paul Strohm was the speaker at our regular lunchtime seminar today and generously agreed to write up a version of his talk as a blog post too, ranging from St Augustine to Albert Camus, via Calvin, Dostoyevsky and Freud.

Paul Strohm was the speaker at our regular lunchtime seminar today and generously agreed to write up a version of his talk as a blog post too, ranging from St Augustine to Albert Camus, via Calvin, Dostoyevsky and Freud.

Paul is Visiting Leverhulme Professor of History and English at Queen Mary, University of London, where he delivered a series of lectures in January and February 2012 on ‘Premodern Interiorities’. His topic today was the relationship between conscience and emotion, and his thoughts were drawn in part from his Conscience: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2011).

I don’t think of conscience as an emotion per se, but as working in close tandem with emotion, as needing emotion for the accomplishment of its aims.

Consider, in this respect, the moment when Augustine, on the brink of conversion but still hesitant, is chided by his angry conscience:

The day came when I was naked to myself and my conscience angrily spoke out within me [increparet in me conscientia mea]: ‘where is my tongue? Indeed, you have said that you would not cast off the burden of vanity for an uncertain truth. Yet others have not exhausted themselves in such a quest, or spent ten years or more thinking about it.’ Thus I was inwardly gnawed [rodebar intus] and violently confused with horrible shame [pudor].

This is an early stirring of conscience—in that it must begin by finding its tongue, its ‘voice.’ And notice that, even in its earliest appearance, his conscience is already irascible [‘angrily spoke out’] and sarcastic besides [‘yet others . . .’]. Its purpose is to unsettle; in this case, to ‘gnaw.’ So conscience is full of attitude . . . but I wouldn’t exactly say that it is an emotion. It knows just what it is doing—has a rational purpose, if you will—and that purpose is to stir an emotion (and, by stirring emotion, to provoke an action in the form of a new choice.)

What Augustine feels as a result of conscience’s prodding—the emotion governing his self-recrimination–is pudor. Pudor here stands at a late Classical/Early Christian crossroads. In its late Classical sense it means ‘shame’, a public emotion, an emotion one feels when ones actions do not measure up to a widely shared norm of good conduct. In its early Christian sense it means ‘guilt,’ a more inward or self-generated (or at least personally embraced) sense of personal wrongdoing.

I want to stay with this idea of conscience as reliant upon, as productive of, the emotions of shame and guilt. These are ‘situated’ emotions, each with its own developmental history. Bernard Williams first made the point I have already alluded to, that shame is most likely to be associated with Greek and classical culture, guilt with Hebrew and Christian culture. And Williams goes on to say something quite suggestive, that we can take back to Augustine’s dilemma:

The most primitive experiences of shame are connected with sight and being seen, but it has been interestingly suggested that guilt is rooted in hearing, the sound in oneself of the voice of judgement.

St Augustine of Hippo as depicted by Sandro Botticelli

Here, in this passage, Conscience shames Augustine by telling him what the world knows about him, how he appears in the eyes of the world: the standard against which Augustine is measured is what other people are doing, how bad this looks for him, to have hesitated for ten years prior to conversion, that there is a community out there which would view him as a malingerer. This humiliation by comparison with public norms is a matter of shame. And Conscience also speaks to Augustine in the voice of moral authority, finds his tongue and uses it to upbraid his errant subject in the ‘voice of judgement,’ an irrefutable voice that Freud will later call the ‘voice of the father,’ a voice ‘quite certain of itself.’ And this is a matter of guilt.

This voice of castigation, this unappeasable voice, has sounded in the ears of believers and, eventually, non-believers alike, for some two thousand years. And it is quite effective in holding people to an external (by the powerful goad of shame) and to an even more elusive and demanding internal mark (by the even more powerful goad of guilt). In fact, it proves such a powerful stimulus to emotion that its biggest problem revolves around the possibility that it might outdo itself. Here, within the evolving Christian tradition, I think of Calvin, who finds in conscience a powerful ally to self-reformation, but one that risks overbearing its subject, and even despairing in the extent of its own task.

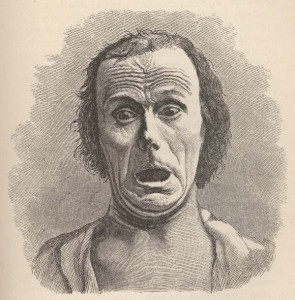

Calvin worries about whether conscience is up to the tasks imposed upon it. He imagines conscience at bay, shaken to the core, wholly intimidated by God’s wrath: ‘When oure conscience beholdeth onely indignation and vengeance, how canne it butte tremble and quake for fear’? This is a conscience that has lost, rather than gained, in self confidence and in capacity to perform its admonitory duties. The result is a form of ‘blowback,’ in which conscience, setting out to provoke salutary guilt in its subject, ends up wracked by its own guilt, including the wholly unproductive emotion of fear: fear, like the most intense of emotions, written on the body, fear that shakes to the core, fear that causes its own subject to ‘tremble and quake.’ This conscience, prey to its own despairing emotions, fails in its primary duty, which is to inspire salutary and reformative emotions in its subject. (Which is why, in Calvin’s system, conscience is itself now in need of reformation, by grace.)

Self punition and festering emotion resurface in the great nineteeth-century critiques of conscience Consider the instance of Ivan Karamazov, the perfect Freudian subject before Freud. Although he does not actually kill his father, he confesses to complicity in the crime because he has wished his father dead. This, then, is an effect of conscience: it generates feelings/emotions of guilt, which lead him to imagine himself complicit in a crime he did not commit. Conscience is, in this sense, gone awry; it provokes an emotion which, rather than leading to reformation, overbears fact and sense.

Calvin found conscience likely to be overborne, overcome by the very emotions of guilt and despair that it set out to instill. Freud goes a step further. He instates guilt not just as conscience’s consequence, but as its point of origin: an apparent effect as cause. A key Freudian perception is that guilt, and conscience as guilt’s abettor, are much freer-floating than we realize, and stand in a different relation to the criminal act than is usually assumed. A standard trajectory would be that you do something wrong and then (prodded by conscience) feel guilty about it. Whereas Freud suggests guilty emotions can precede the criminal act, can be its incentive.

All these critics of conscience see it as operating improperly, as overbearing on the one hand or stalled and festering on the other. The stalled conscience is a distinctively twentieth-century predicament, and this is a conscience in which emotion, rather than exceeding its mandate, simply fizzles out—deserts conscience and leaves it foundering.

A literary rendering of such a case would be the character Clamance, in Camus’ The Fall (La Chute, 1956). Camus elsewhere describes him as ‘the exact illustration of a guilty conscience.’ Yet in this case his guilt lacks emotional purchase, has not roused him to action. Clamance’s conscience is constituted by a ‘cry’ uttered by a woman drowning herself in the Seine, a cry which ‘waited for me until the day I encountered it’ and to which ‘I had to submit and admit my guilt’. This is a cry to which Clamance was initially unable to respond, and his inability to respond to it—even to know whence it has issued or what it wants from him–now debars his return to an untroubled life. His guilt, in this case, has become something other than a spur to action; it is pervasive but nerveless and inert, less an emotion, if we think of emotion as an affective feeling, than a continuing philosophical predicament, a state of affairs. Clamance has a conscience, to be sure; he is suffering from a predicament of conscience, an excess of it. What he needs now is some affect, some accompanying emotion. Even though emotion, strongly felt, can be unpredictable or erratic in its consequences, he lacks the incentive to choice and action that only emotion can provide.

A literary rendering of such a case would be the character Clamance, in Camus’ The Fall (La Chute, 1956). Camus elsewhere describes him as ‘the exact illustration of a guilty conscience.’ Yet in this case his guilt lacks emotional purchase, has not roused him to action. Clamance’s conscience is constituted by a ‘cry’ uttered by a woman drowning herself in the Seine, a cry which ‘waited for me until the day I encountered it’ and to which ‘I had to submit and admit my guilt’. This is a cry to which Clamance was initially unable to respond, and his inability to respond to it—even to know whence it has issued or what it wants from him–now debars his return to an untroubled life. His guilt, in this case, has become something other than a spur to action; it is pervasive but nerveless and inert, less an emotion, if we think of emotion as an affective feeling, than a continuing philosophical predicament, a state of affairs. Clamance has a conscience, to be sure; he is suffering from a predicament of conscience, an excess of it. What he needs now is some affect, some accompanying emotion. Even though emotion, strongly felt, can be unpredictable or erratic in its consequences, he lacks the incentive to choice and action that only emotion can provide.

When Wilhelm Reich, the most brilliant of the second generation of psychoanalysts who had been Freud’s pupils, arrived in New York in August 1939, only a few days before the outbreak of war, he was optimistic that his ideas fusing sex and politics would be better received there than they had been in fascist Europe. Despite its veneer of puritanism, America was a country already much preoccupied with sex – as Alfred Kinsey’s renowned investigations, which he had begun the year before, were to show. However, it was only after the second world war that the idea of sexual liberation would permeate the culture at large. Reich could be said to have invented this “sexual revolution”; a Marxist analyst, he coined the phrase in the 1930s in order to illustrate his belief that a true political revolution would be possible only once sexual repression was overthrown. That was the one obstacle Reich felt had scuppered the efforts of the Bolsheviks. “A sexual revolution is in progress,” he declared, “and no power on earth will stop it.”

When Wilhelm Reich, the most brilliant of the second generation of psychoanalysts who had been Freud’s pupils, arrived in New York in August 1939, only a few days before the outbreak of war, he was optimistic that his ideas fusing sex and politics would be better received there than they had been in fascist Europe. Despite its veneer of puritanism, America was a country already much preoccupied with sex – as Alfred Kinsey’s renowned investigations, which he had begun the year before, were to show. However, it was only after the second world war that the idea of sexual liberation would permeate the culture at large. Reich could be said to have invented this “sexual revolution”; a Marxist analyst, he coined the phrase in the 1930s in order to illustrate his belief that a true political revolution would be possible only once sexual repression was overthrown. That was the one obstacle Reich felt had scuppered the efforts of the Bolsheviks. “A sexual revolution is in progress,” he declared, “and no power on earth will stop it.” Yesterday I went to an excellent conference on revelatory experiences at the Institute of Psychiatry, which brought together neuroscientists, psychiatrists, psychologists, historians, theologians and members of the public (many of whom had revelatory experiences – turns out they’re pretty common!)

Yesterday I went to an excellent conference on revelatory experiences at the Institute of Psychiatry, which brought together neuroscientists, psychiatrists, psychologists, historians, theologians and members of the public (many of whom had revelatory experiences – turns out they’re pretty common!)

Dr Lockley showed that historians can tell us interesting things about how revelatory experiences are culturally constructed and influenced by their time. For example, Dr Shaw told us how the language of inspiration in the Panacea Society was inspired by the invention of the wireless – the mediums talked of ‘tuning in’ to God – a phrase which was subsequently taken up and popularised by Timothy Leary and the LSD counterculture. The movement was also part of the ferment during World War I – it was fiercely patriotic, and members of it lobbied the Archbishop of Canterbury to open the ‘sealed box of prophecies’ left by the 18th century visionary Joanna Southcott, which she said should be opened in a time of national crisis by the 24 bishops of the nation (here’s the box on the left). I personally think the opening of the box should be the climax of the Olympics inauguration ceremony.

Dr Lockley showed that historians can tell us interesting things about how revelatory experiences are culturally constructed and influenced by their time. For example, Dr Shaw told us how the language of inspiration in the Panacea Society was inspired by the invention of the wireless – the mediums talked of ‘tuning in’ to God – a phrase which was subsequently taken up and popularised by Timothy Leary and the LSD counterculture. The movement was also part of the ferment during World War I – it was fiercely patriotic, and members of it lobbied the Archbishop of Canterbury to open the ‘sealed box of prophecies’ left by the 18th century visionary Joanna Southcott, which she said should be opened in a time of national crisis by the 24 bishops of the nation (here’s the box on the left). I personally think the opening of the box should be the climax of the Olympics inauguration ceremony. I come from a Yorkshire Quaker family, and I remember my great-grandmother telling a story about a woman standing up during a Quaker meeting, moved by the Holy Spirit, and proclaiming: ‘Raspberry ripple with a cherry on top’. Well, yes, I mean, absolutely, I’m all for raspberry ripples, particularly with a cherry on top, but that’s not a revelation I will spend much time studying or following, because of my own value judgement about its quality or meaningfulness. (Although shortly afterwards, another Quaker family, the Frys, launched a chocolate called Ripple. Make of that what you will.)

I come from a Yorkshire Quaker family, and I remember my great-grandmother telling a story about a woman standing up during a Quaker meeting, moved by the Holy Spirit, and proclaiming: ‘Raspberry ripple with a cherry on top’. Well, yes, I mean, absolutely, I’m all for raspberry ripples, particularly with a cherry on top, but that’s not a revelation I will spend much time studying or following, because of my own value judgement about its quality or meaningfulness. (Although shortly afterwards, another Quaker family, the Frys, launched a chocolate called Ripple. Make of that what you will.)