This is a guest-post by author and psychologist Hilda Reilly.

Playthings, Alex Pheby’s second novel, is based on the case of Daniel Paul Schreber, a 19th century German judge afflicted by schizophrenia. Unusually for a patient of that era, he wrote an extensive account of his psychotic experiences and long periods of hospitalization, later published as Memoirs of my Nervous Illness. The case has been made famous by Sigmund Freud who wrote his own interpretation of Schreber’s illness, although the two never met in person.

Playthings, Alex Pheby’s second novel, is based on the case of Daniel Paul Schreber, a 19th century German judge afflicted by schizophrenia. Unusually for a patient of that era, he wrote an extensive account of his psychotic experiences and long periods of hospitalization, later published as Memoirs of my Nervous Illness. The case has been made famous by Sigmund Freud who wrote his own interpretation of Schreber’s illness, although the two never met in person.

Crucial to the case is a knowledge of Schreber’s family background. His father, Moritz Schreber, was a medical doctor and child-rearing expert whose many books on the subject achieved a popularity which seems astonishing when judged by today’s standards of child care. He it was who devised the harsh and punitive regime of upbringing imposed on his own children from the age of just a few months, a regime described by Morton Schatzman, author of Soul Murder – an analysis of the Schreber case – as ‘household totalitarianism’.

Freud’s and Schatzman’s are probably the most prominent of the analytical works published on Schreber and they are at odds with each other, Freud linking his psychotic condition to repressed homosexual desire for his father and his brother, Schatzman imputing it rather to his father’s repressive disciplinarianism. In Playthings Pheby seems to subscribe to the latter theory.

The question of whether or not any author can adequately represent the reality of another person by attempting to think himself into that person’s consciousness and portraying the findings in a work of ‘faction’ is a controversial one. Yet any rendering of the past is mediated through the specific consciousness of the narrator, with all that that implies in terms of formative forces acting on the narrative produced. Indeed we might question to what extent Schreber himself was a reliable narrator.

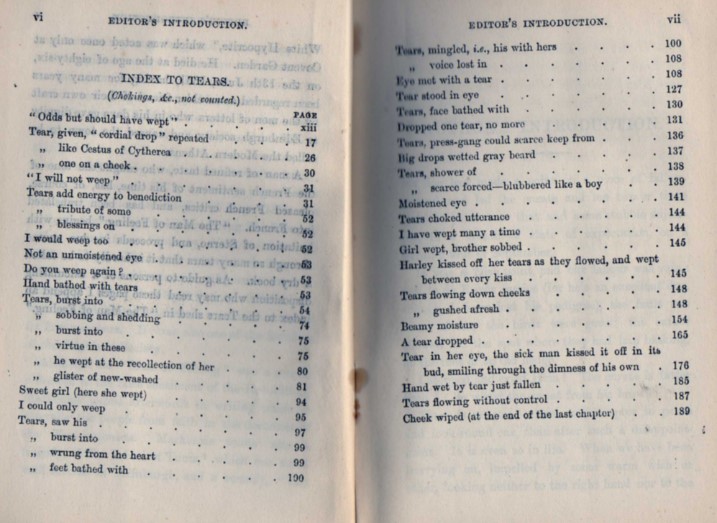

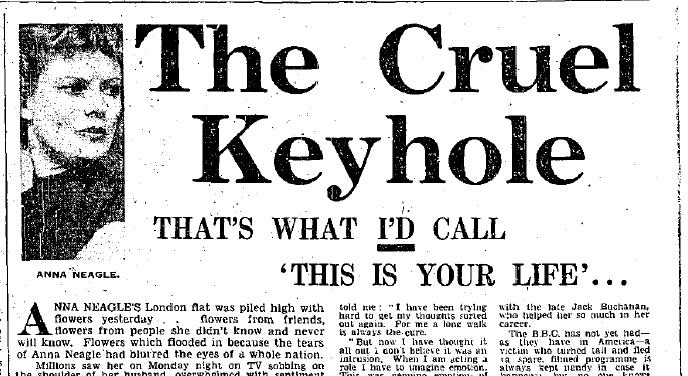

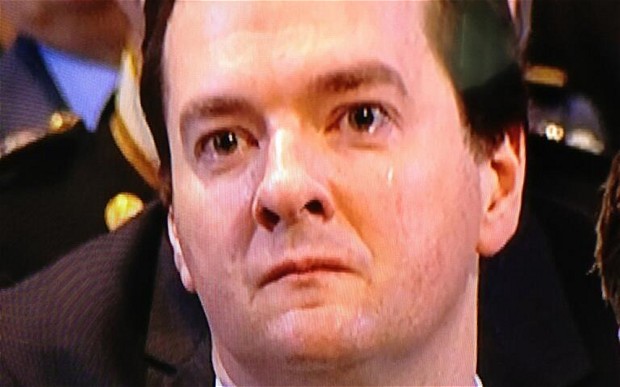

Memoirs was written towards the end of Schreber’s second hospitalisation, when he was trying to secure his release. There is undoubtedly something of the splendid in Memoirs, with its magnificent architecture of exuberant hallucinatory imagery and its elaborately surreal cosmology. Yet it is recorded with almost an air of detachment, as if written by a third person rather than directly by the experiencer himself. There isn’t the sense of confusion, disorientation, menace even, that might be expected to flavour a first-hand account. As Rosemary Dinnage comments in her Introduction to the New York Review Books Classics edition: ‘What remains missing up to the end is feeling itself: no tears are recorded.’ Was this a deliberate strategy on Schreber’s part, adopted to help him secure his release? At the very least, we should bear in mind that, although based on notes made while his illness was at its height, it was rendered into its final form when he was in the recovery stage, when some of the vigour of the original experiences would be lost, even in his own memory.

Pheby could have chosen the time frame of the novel to correspond with Schreber’s first or second hospitalisation, the periods covered by Memoirs; he could then have produced a dramatisation of Schreber’s own testimony which would, of course, have resulted in an entirely different kind of novel, and one possibly less challenging for both writer and reader.

He opted instead to set it in Schreber’s third, and last, hospitalisation, for which we have no reports from Schreber and little other information. This, of course, gives Pheby greater creative freedom and, given his stated aim of ‘exploring the psychological structure of fascism, the cancer of anti-Semitism, and the abuse of institutional power’, it is understandable why he would have felt the need for this freedom.

The style Pheby has adopted for Playthings seems to be inspired by that of Memoirs. As with Memoirs, I found it curiously devoid of emotion. There is a similar sense of dry detachment in the narration. Schreber’s mind never seems quite out of control. His conversations with hallucinated individuals struck me as too measured and coherent to be consistent with the kind of dialogue experienced in psychotic conditions. Even Schreber himself, for all his control, goes further; for example, in Memoirs he refers to the voices as “nonsensical twaddle”; or again, “……..the talk of the voices had already become mostly an empty babel of ever-recurring monotonous phrases in tiresome repetition; on top of this they were rendered grammatically incomplete by the omission of words and even syllables.” There is none of this raggedness of speech in Playthings, little of the flamboyant surreality that is found in Memoirs.

There is also surprisingly little of the religious preoccupations that feature so prominently in Schreber’s own writing. Instead much of the action is devoted to filling in Schreber’s backstory as he remembers or relives events from his strict childhood. Some of those events are based on known fact, such as his father’s accident, and others invented; for example, when the young Schreber put his baby sister to his own nipple. But whether real or fictional, they are designed to provide an explanatory framework for Schreber’s later condition.

The writing style is almost minimalist, but also studded with idiosyncratic descriptive detail. Pheby is master of the eloquent phrase: a hand ‘that was thin to the point of brittleness – like a twig one finds on the forest floor late into the autumn‘; anger which ‘filled the room like steam from an untended kettle‘. The menace is allowed to grow quietly, particularly via the person of Muller, the aggrieved and sinister orderly, who comes into his full sadistic own when Schreber is confined, helpless, in an isolation cell for recalcitrant patients.

In reading Playthings I found that I had to stop fairly early on to find out more about Schreber, his illness and his work before reading any further. In fact, throughout the book I had to keep checking the record in this way and I feel that without that background information I would have had less appreciation of the book. As yet Pheby has no information about Playthings on his website. I hope this will be rectified. It would be fascinating to get more insight into the author ’s thinking about both Schreber himself and the creation of the novel. It would also be illuminating to have the book reviewed by someone who has experience of a psychotic condition similar to Schreber’s. Only such a person can truly judge to what extent Pheby succeeds in conveying ’what it’s like’ (in Nagel’s sense) to have this kind of mental disturbance.

But perhaps the novel form is unsuited to accommodating a full-blown representation of schizophrenia. We expect a novel to make some sort of sense; we expect to be able to arrive at some understanding of the characters; we expect, however loosely, a beginning, a middle and an end. Playthings provides all this, and given the difficulty of finding these criteria realised in actual cases of psychosis we can hardly expect fiction to achieve it without a degree of compromise.

Although I can’t say I enjoyed reading Playthings in any recreational sense – it’s not a novel I would recommend for a long-haul flight – I found it stimulating to read in the context of the wider Schreber literature and as a spur to further reflection on the validity of the biographical novel as a literary genre.

Hilda Reilly has an MSc in Consciousness and Transpersonal Psychology and an MA in Creative Writing. She is the author of Guises of Desire, a biographical novel about Bertha Pappenheim, aka Anna O, the ‘founding patient‘ of psychoanalysis.

The Centre for the History of the Emotions at Queen Mary University of London seeks to appoint a Project Manager to co-ordinate the activities of a new Wellcome Trust Humanities and Social Science five-year Collaborative Award: ‘Living With Feeling: Emotional Health in History, Philosophy, and Experience’. The award will support an ambitious programme of inter-disciplinary research and public engagement into the history and meanings of ‘emotional health’. An announcement of the new award was

The Centre for the History of the Emotions at Queen Mary University of London seeks to appoint a Project Manager to co-ordinate the activities of a new Wellcome Trust Humanities and Social Science five-year Collaborative Award: ‘Living With Feeling: Emotional Health in History, Philosophy, and Experience’. The award will support an ambitious programme of inter-disciplinary research and public engagement into the history and meanings of ‘emotional health’. An announcement of the new award was