After the publication of What is the history of emotions? Part I and Part II, to mark the blog’s first birthday, I issued a general invitation for further answers to this question. The wonderful results are now published here as a third (and final?) instalment.

Three of these six responses are from PhD students and three from established scholars. Sally Holloway writes about romance and material culture, Åsa Jansson about the profound significance of our changing notions of mental disorder, and Anna Kennedy about the continuing relevance of Jean-Paul Sartre to modern psychology. Then Emma Mason uses the poetry of e. e. cummings to get us to think about feelings, literature, science and education; Katherine Angel brings to life the problems of historical distance and identification through the diaries of Samuel Pepys; and finally Rowan Boyson refelects on a surprising emotional overlap between the history of science and the philosophy of aesthetics.

Sally Holloway

PhD Student, Royal Holloway, University of London

The history of emotions for me is a history of language, of objects, and of symbolism, which is firmly embedded in the material world. This approach has been shaped by my doctoral research on romantic love in premarital relationships between c. 1730 and 1830. I was first introduced to emotion history via the history of letter-writing, with Fay Bound Alberti’s article ‘“Writing the Self”: Love and the Letter in England c. 1660-1760’ in Literature and History (2002.) She presented love letters as a ‘highly specific way of shaping as well as reflecting emotional experience.’ This experience was not expressed at random, but within a framework of cultural and social references which ensured that the content and structure of letters was ‘no less crafted than church court depositions.’

While it would take a mind-reader to know how lovers actually felt, we can nonetheless access how individuals processed, conceptualised and expressed their emotions. My research approaches romantic love as a cultural construct which was shaped by a number of medical, religious and literary conventions. When writing love letters, individuals could adopt or jettison these conventions as they pleased. For example when the Quaker flour merchant Thomas Kirton wrote to his future wife Olive Lloyd in 1734, he recognised that,

I know Heroick Love, and Friendship are things out of Fashion, and thought fit only for Knights Errant…But I condemn their low Ideas, ’Tis thy Noble mind, as well as comely Personage, I so much admire.

This demonstrates how Thomas’s concept of love was neither ‘innate’ nor ‘unchanging’, but shifted over time in accordance with wider romantic movements. Particular tropes came in and out of vogue, with Thomas deciding to call upon heroic love to conceptualise his emotions, even though it was not deemed fashionable at the time.

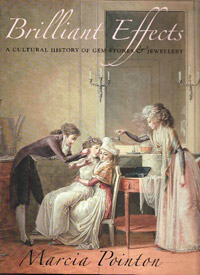

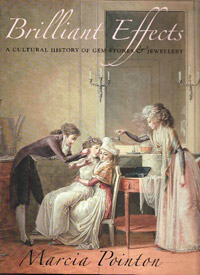

Emotions such as romantic love were also formulated using the haptic pleasures of ‘love objects.’ Love was a sensual experience, as individuals worked through their feelings by touching, smelling and gazing at gifts given by lovers. This encouraged them to think deeply about a relationship and consider how they felt about the giver, also allowing them to gauge the intensity of their passion. In providing access to this secretive and often undocumented act, the history of emotions is unique in taking romantic love below the level of literacy. My research into objects and emotion has been strongly influenced by anthropological works such as Marcel Mauss’s The Gift (trans. 1954) and Pierre Bourdieu’s Outline of a Theory of Practice (trans. 1977.) I have also been inspired by Marcia Pointon’s landmark study Brilliant Effects (2009) which explores the material, emotional and symbolic dimensions of gemstones and jewellery. Several interesting articles have been posted on this blog on this topic, such as Jenny Nyberg on ‘Grave Emotions’ and Thomas Dixon on ‘The Stuff Emotions Are Made Of.’

Emotions such as romantic love were also formulated using the haptic pleasures of ‘love objects.’ Love was a sensual experience, as individuals worked through their feelings by touching, smelling and gazing at gifts given by lovers. This encouraged them to think deeply about a relationship and consider how they felt about the giver, also allowing them to gauge the intensity of their passion. In providing access to this secretive and often undocumented act, the history of emotions is unique in taking romantic love below the level of literacy. My research into objects and emotion has been strongly influenced by anthropological works such as Marcel Mauss’s The Gift (trans. 1954) and Pierre Bourdieu’s Outline of a Theory of Practice (trans. 1977.) I have also been inspired by Marcia Pointon’s landmark study Brilliant Effects (2009) which explores the material, emotional and symbolic dimensions of gemstones and jewellery. Several interesting articles have been posted on this blog on this topic, such as Jenny Nyberg on ‘Grave Emotions’ and Thomas Dixon on ‘The Stuff Emotions Are Made Of.’

The history of emotions is therefore paramount in providing us with new ways of looking at romantic relationships. It does so through numerous intersections with gender history, social history, cultural history, anthropology and material culture. This allows historians to move beyond age-old debates about marriage for love which have dominated the last three decades, creating new insights into how couples related to one another.

Åsa Jansson

PhD Student, QMUL Centre for the History of the Emotions

I was partly drawn to the history of the emotions because I was curious about the origins of current ideas about emotionality and what it means to be human. But in the first instance my work within this field is not motivated by curiosity but by concern. I came to the history of the emotions via the history of psychiatry, and these two spheres are still very much intertwined in my own research, joined to some extent by neuroscience and psychology. For these are disciplines which purport to say something about what we are and why. And, more importantly, they are concerned with (to put it bluntly) ‘discovering’ what is wrong with people and why. Since psychiatry’s infancy there have been, and continue to be, attempts made to explain pathological emotionality in biological language. Indeed, the modern idea that our emotions have a cerebral basis and as such are prone to become disordered was largely invented in the early nineteenth century through an appropriation of language from experimental physiology to the realm of thoughts and feelings. The science(s) underpinning biomedical explanations of the emotions and their disorders is of course in many ways very different today. But the basic understanding of the emotions as automated, cerebral, and subject to disorder and disease continues to facilitate research in the psy-disciplines and the neurosciences in the twenty-first century.

So what is it about this that concerns me? Well, when we use ‘scientific’ language to talk about such highly ethical, social, relational, and – above all – historically contingent questions as what human beings feel and think and when we do so under the assumption that such language is factual and value-neutral, we often fail to take responsibility for the potential consequences of our words. To label emotions and, by extension, people in certain ways, to categories them as ‘pathological’, ‘abnormal’, or ‘disordered’, and to suggest that these features are inscribed into bodies and brains, have a potentially vast range of ethical consequences for individuals who find themselves subject to such labels or who, as is also often the case, adopt and internalise them.

We are often inclined to think that those aspects of our lives which, because they are personal and intimate, we tend to perceive as ‘natural’, ‘innate’, and ‘inevitable’ (such as our emotions) are constant and universally true. But just as ideas about nature and innateness have a history, so do the emotions and the belief that these can be a source and site of pathology, of illness. Thus, one of the things we can learn from taking a historical perspective on the emotions is that our present understanding of ‘emotional disorders’ is historically specific; it was once created, made – and this importantly implies that it can be unmade. For me this is where the history of the emotions becomes more than storytelling or academic pursuit: it shows us that things can change, including the possibilities and limits of human experience. Such history holds the promise of hope, of a future different from both the present and the past.

Anna Kennedy

PhD Student, Psychology, University of Edinburgh

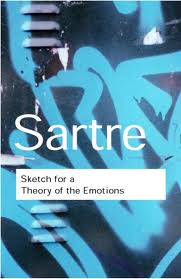

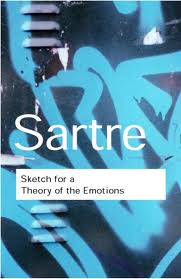

As a first year PhD student looking at how emotions have been defined and operationalized as they are studied by psychologists, my interest in the history of emotions lies in what it can reveal about the constructed and constructive nature of psychological understandings. Amongst the vast emotions literature, one of the most inspiring books that has stood out for me is Sartre’s Sketch for a Theory of Emotion, which I think sets out some revealing arguments regarding the ability of psychologists to get at a phenomenon which continues to defy definition.

In it Sartre argues that in the gathering of facts about emotion, psychologists will never capture its essence nor what it is to be an emotional being. As a historian of psychology I can see that over time psychological facts about emotion (e.g. physiological responses, eliciting stimuli, neuroscientific data) change, as the methods of gathering them alter. The self-acknowledged struggle of psychologists to define and capture emotion reflects the inability of these changing facts to uncover Sartre’s ‘essence’. No matter how many connected elements are collected and built one on the other they will never reach a whole which is able to fully represent the meanings that pervade people’s emotional lives.

In it Sartre argues that in the gathering of facts about emotion, psychologists will never capture its essence nor what it is to be an emotional being. As a historian of psychology I can see that over time psychological facts about emotion (e.g. physiological responses, eliciting stimuli, neuroscientific data) change, as the methods of gathering them alter. The self-acknowledged struggle of psychologists to define and capture emotion reflects the inability of these changing facts to uncover Sartre’s ‘essence’. No matter how many connected elements are collected and built one on the other they will never reach a whole which is able to fully represent the meanings that pervade people’s emotional lives.

This struggle was captured, rather wittily, by P.T. Young in 1973, who said, “…almost everyone except the psychologist knows what emotion is.”. Of course, psychologists are people too so are very well acquainted with emotion and perhaps this is the problem. In comparing their scientific definitions with their experience they understand their inadequacy to fully capture emotion but are bound by the pursuit of data gathering to operationalize it narrowly and in accordance with what is viewed as scientific at particular points in time. It is the studying of these points of time and what they have to reveal about changing psychological conceptualisations of emotion that I hope will provide both a challenge and a background to current theorizing as illustrated by this quote from Robert Solomon in relation to the highly contested idea of basic emotions, ‘I would argue that the notion of “basic emotions” is neither meaningless nor so straightforward as its critics and defenders respectively argue, but it is historical and culturally situated and serves very different purposes in different contexts, including different research contexts…It is a subject with a rich history, and it is not one that can be readily understood within the confines of a technical debate in the Psychological Review.’

Emma Mason

University of Warwick

since feeling is first

since feeling is first

who pays any attention

to the syntax of things

will never wholly kiss you;

wholly to be a fool

while Spring is in the world

my blood approves,

and kisses are a better fate

than wisdom

lady i swear by all flowers. Don’t cry

—the best gesture of my brain is less than

your eyelids’ flutter which says

we are for each other: then

laugh, leaning back in my arms

for life’s not a paragraph

And death i think is no parenthesis

I open this short blog entry on emotion and literature with e. e. cummings’ poem ‘since feeling is first’, the text with which I begin my undergraduate module ‘Poetry and Emotion’. I have been teaching this module for seven years and have found it a useful forum in which to think with students about the overlap between an emergent interest in ‘affect theory’ and a simultaneous return to formalism. I turn to this relationship between feeling and form below, but with a mind-set newly invigorated by a recent statement issued by Dr Wendy Piatt, the Director General of the Russell Group, about the status of literary studies in the UK. As a member of a University that is on paper part of the Russell Group, I was especially surprised, shocked even, disheartened certainly, to read Dr Piatt’s declaration that: ‘There has been too much focus on an “emotional” response to texts rather than on robust critical analysis in some subjects like English’ in a wider statement about Ofqual’s recent report on A level teaching.

Readers of this blog will be long familiar with the binary Piatt sets up here between reason and emotion, rationality and excitability, ‘robust’ scholarship and sentimental studies, and will not need to be reminded of the essential sexism implied in such a statement (English is too schmaltzy, too many girls study it anyway, and we need to make the study of it a better transition into Law or Business Studies to secure the clever boys on our degrees). The statement recalls the kind of anxiety F. R. Leavis expressed about literary studies in the 1930s: to paraphrase his debut essay for Scrutiny, ‘The Literary Mind’ (1932-33), the study of the emotional content of a literary text should focus on a structured sensibility to help develop cerebral muscle, and not issues of sentimentality and excessive expressionism.

Piatt’s statement also serves as a response to Ofqual’s insistence that literary studies needs the ‘Brian-Cox-effect’ to ‘save’ it from dissolving into mere empathetic humanism. Cox, like Richard Dawkins, sells the ‘worth’ of science from both an unchallenged assumption about its ability to present the world as it ‘really is’ (or at least its capacity to one day think up the equation to do so); and also the ‘wonder’ and ‘beauty’ of this ‘reality’ (cue both Cox and Dawkins caught on camera in various documentaries staring into sunsets and across mountain ranges content in the belief that such loveliness issues from ‘science’ and not a creator God). This clip of Cox interviewing Stephen Hawking reveals just how obsessed many scientists still are with ‘creation’, a word those same scientists believe they have a completely neutral stance towards, self-fashioned as they are as the objective defenders of what Dawkins calls the ‘mumbo jumbo’ of religion, spirituality, alternative medicines and other emotionally-led delusions. Thomas Dixon has written elsewhere of the danger of reducing the study of emotion to ‘psychoanalysis, cognitive science, or neuropsychology’, a move that threatens to ‘give up at the outset on the possibility of reconstituting the affective life of the past and to undertake instead a fishing expedition for data in support of modern psychology.’ Literary critics too are at the same risk of attempting to explain away emotion in terms other disciplines, the current favourite being neuroscience.

At a conference called ‘Languages of Emotion’ that I organized with Isobel Armstrong in 2004, a largely Humanities-based audience listened to a keynote by the neuroscientist Edmund Rolls, an engaging talk that nevertheless highlighted for me the unbridgeable gap between this kind of thinking and the study of poetry. I have taught the work of Antonio Damasio and Joseph LeDoux to exceptionally brilliant undergraduates at Warwick for several years on ‘Poetry and Emotion’, but recently removed it after finally deciding that, while an incredibly compelling subject in its own right (I am an avid reader of popular science), it wasn’t helping students develop an analysis, exposition or emotional sense of a poem. A ‘helpful’ text, I think, is one that allows a student to explore the cultural and historical context, formal and phenomenological feeling of a poem, so that he or she can write an essay that stays with the poem and does not wander off from it into an abstracted discussion of something else. Robert Harrison makes a more pointed criticism of neuroscience in a discussion about Jean-Paul Sartre as part of his Stanford University Entitled Opinions podcast series, well worth listening to for its insistent attention to questions of emotion and the felt experience of the world. For Harrison, ‘our age’ suffers from a ‘malady’ that ‘has to do with the unrestrained drive in contemporary biology, neuroscience, artificial intelligence and cognitive science to reify human consciousness, that is to say, to view it in materialist terms as if consciousness were a biological phenomenon on the order of things in the world, or what Sartre called “the in itself”. Sartre shows . . . that all attempts to reduce human beings to a status of a thing are not only doomed to failure, they are part of the tragedy of consciousness’ alienation from the order of positive being’.

For me, poetry connects students back to ‘positive being’ without falling into a moral-driven humanism about right behavior or goodness: as Henri Meschonnic puts it, ‘Only the poem can unite, hold affect and concept in one mouthful of speech which acts, transforms our manner of seeing, hearing, feeling, understanding, talking, reading’ (‘The Rhythm Party Manifesto’, 2001, trans. 2011). I am not interested in the question of whether we become ‘better people’ by reading poetry, but I do think working on focused ways into poems (like close reading) engenders a way of addressing how emotions are experienced by us, how they circulate and adapt to material spaces and places, as well as how they are transmitted, expressed, constructed and felt.

From William Wordsworth’s proclamation about poetry as an overflow of feeling to cummings’ sense of poetry as a way into questions of ‘lookiesoundiefeelietastiesmellie’ and Elizabeth Bishop’s understanding of it as an  ‘uncomfortable feeling of “things” in the head’, poetry is consistently theorized through emotion, not only by poets, but also by philosophers, anthropologists and theologians. A great example of a book with which I replaced Damasio and LeDoux is Kathleen Stewart’s Ordinary Affects (2007), a study that evolves affect theory into a mode of critical storytelling that is able to sympathetically perceive and attend to the minutiae of the affective dimensions of everyday life. An anthropologist, Stewart enacts a meditative thinking we might associate with Martin Heidegger or Simone Weil by patiently detailing moments of everyday life through a ‘nomadic tracing’ and poetic ‘attunement’ to present moment experience. This focus on attunement to the experience of a text finds resonance in those studies of emotion unafraid to link ‘feeling’ to bigger questions of religion, faith, compassion and relationalism. Both Lauren Berlant’s work on compassion and Teresa Brennan’s exploration of the transmission of affect do this, experimenting as they do with a religious language of care and attention to think through feeling and so speak to a new prosody equally interested in understanding how poems shape us as readers, both physically and emotionally.

‘uncomfortable feeling of “things” in the head’, poetry is consistently theorized through emotion, not only by poets, but also by philosophers, anthropologists and theologians. A great example of a book with which I replaced Damasio and LeDoux is Kathleen Stewart’s Ordinary Affects (2007), a study that evolves affect theory into a mode of critical storytelling that is able to sympathetically perceive and attend to the minutiae of the affective dimensions of everyday life. An anthropologist, Stewart enacts a meditative thinking we might associate with Martin Heidegger or Simone Weil by patiently detailing moments of everyday life through a ‘nomadic tracing’ and poetic ‘attunement’ to present moment experience. This focus on attunement to the experience of a text finds resonance in those studies of emotion unafraid to link ‘feeling’ to bigger questions of religion, faith, compassion and relationalism. Both Lauren Berlant’s work on compassion and Teresa Brennan’s exploration of the transmission of affect do this, experimenting as they do with a religious language of care and attention to think through feeling and so speak to a new prosody equally interested in understanding how poems shape us as readers, both physically and emotionally.

My sense is that the most effective recent example of thinking through the physical and emotional ‘impact’ of reading poetry is Isobel Armstrong’s reading of metre as ‘the product of a somatic pressure encouraged by the sound system of the poem’s language, abstracted by the mind, and returned to language and the body when the poem is read in real time’ (‘Meter and Meaning’, 2011). As Armstrong argues, one has to feel metre: you can’t google a remembered sound pattern, as students soon learn on ‘Poetry and Emotion’ as they are asked to think through and sound out rhyme and rhythms in poems by writers like Tennyson, Rossetti, Poe, Cavafy, Rilke, Basho, Plath, Hughes, Merwin and Prynne. The return to form, like the study of emotion, shows a willingness to address those aspects of life that structure existence, but can’t be catalogued and archived or accounted for or banked. Whatever science discovers about the way we feel (from theories that locate it all within the brain, to those that envision us as computer-generated projections of an advanced alien culture) and where we feel it (in multi-verses and multi-dimensions), we still have to find ways to emotionally relate to others in ‘real time’ and understand and reflect on that relation. I imagine this kind of learning experience would not be deemed ‘robust’ enough for some, although I’m sure even Dr Piatt would be relieved to encounter the challenge of reading Heidegger and Brennan, Weil and Sartre, Barthes and Tanizaki, that accompanies the discussion of poems on ‘Poetry and Emotion’. Literary studies is inherently guilty of being worried about appearing ‘soft’ (and by association ‘feminine’), but that softness offers us a unique way into thinking and feeling possibilities and potentialities for human change, respect, empathy, hospitality towards others and what Stanley Hauerwas calls a politics of gentleness that might challenge the politics of aggression that currently dominates western politics. At the same time, poems about feeling, both happy (hymns of joy and declarations of love) and sorrowful (elegies and epitaphs that explore mourning and loss), are remembered and relied upon by people of various communities, and finding a way to think and write about that value is worth pursuing at all levels of education. ‘since feeling is first’ we literary critics might not be as defensive as we sometimes appear about teaching poems that move us emotionally as well as intellectually.

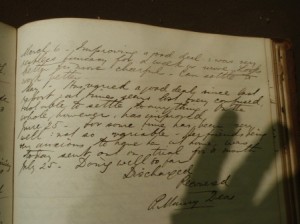

On 13th October 1660 Samuel Pepys wrote the following in his diary:

To my Lord’s in the morning, where I met with Capt. Cuttance. But my Lord not being up, I went out to Charing cross to see Maj.-Gen. Harrison hanged, drawn, and quartered – which was done there – he looking as cheerfully as any man could do in that condition. He was presently cut down and his head and heart shown to the people, at which there was great shouts of joy. … Thus it was my chance to see the King beheaded at Whitehall and to see the first blood shed in revenge for the blood of the King at Charing cross. From thence to my Lord’s and took Capt. Cuttance and Mr Sheply to the Sun taverne and did give them some oysters. After that I went by water home, where I was angry with my wife for her things lying about, and in my passion kicked the little fine Baskett which I bought her in Holland and broke it, which troubles me after I had done it. Within all the afternoon, setting up shelfes in my study.

When I first read this, decades ago, I was fascinated, and shocked, by the matter-of-factness with which Pepys recounts both these gruesome events and the subsequent mundanities of his day. I was struck also by the contrast between my own sense of horror at these barbarities – a feeling that runs so deep, and seems so natural, so inevitable! – and the apparent enthusiasm for it in Pepys’ day: the ‘shouts of joy’. And I was intrigued, and not a little appalled, that Pepys himself seemed so unappalled.

An early lesson, then, in historical difference; in the historical contingency of our situations and perspectives; of what feel like our deepest, truest emotions. A difference that is all the more unsettling because Pepys also strikes us, in pangs of recognition, as so like us: he goes to the pub, he gets angry, he puts up bookshelves.

Later, reading this passage again, I noticed different elements: the gently sardonic tone of ‘he looking as cheerfully as any man could do in that condition’. I noticed that Pepys is observing the crowd, describing their shouts of joy – he is not clearly a participant. I noticed the somewhat distant, ironic commentary on the historical vagaries of the time – seeing Thomas Harrison, a signatory to Charles I’s death warrant, take his turn on the platform; seeing the hangman, if you like, hanged. I also found myself wondering if Pepys was as impassive as I had first thought in the face of the hanging; I found myself speculating that his anger may have been triggered by distress at the hangings. Surely one would have to have an outlet for the distress that one would inevitably, deeply, feel in the face of such violence? Surely?

And then I noticed the presumption involved in this – for by this time I was knee-deep in the history of psychiatry, and thinking about the rise of models of the mind involving unconscious motivations, and the rise in the twentieth century in particular of depth psychology and psychoanalysis. I became, then, self-conscious about the assumptions that my responses to Pepys’ writings contained – assumptions about the historical continuity of psychological and emotional categories, an imagined continuity that underpinned my sense of identification with Pepys. The presumption that this gesture of understanding is possible was further challenged by reading Michel Foucault, in particular his History of Sexuality. What Foucault does is historicise, and reveal the contingency of, the very structure of how we think about sex and the self. He historicises our deepest feelings about our deepest feelings: in particular, our feeling that sex is somehow constitutively enmeshed with what it is to be a person; our view that sex is something about which the ‘unbearable, too hazardous truth’ must be told; our conviction that writing the history of sex must be told through the constitutive element of ‘prohibition’. A conviction which is, Foucault tells us, a ruse.

What Pepys’ Diary does is reveal a range of ways in which emotions can be historicized. Pepys examines his thoughts and feelings, observing them in a way which opens up a space for thinking about their formation, their history. For example:

This day I was told that my Lady Castlemayne (being quite fallen out with her husband) did yesterday go away from him with all her plate, Jewells and other best things; and is gone to Richmond to a brother of hers; which I am apt to think was a design to get out of town, that the King might come at her the better. But strange it is, how for her beauty, I am willing to conster all this to the best and to pity her wherein it is to her hurt, though I know well enough she is a whore.

Pepys doesn’t question his perception of Lady Castlemayne as a whore – that might be asking too much – but he does notice that his appreciation of her beauty makes him more lenient in his judgement of her. The contingency of his own judgements and feeling, their shaping by other feelings, is, in this way, opened up to him and to us.

Passages such as the first I quoted, in which we are unsettled by apparent emotions (or their absence), alongside human experiences we feel such resonance with, allow us to sense the importance of other ways of historicizing emotions: seeing in what way emotional repertoires, and their understanding, change over time. They also, therefore, allow us to feel the importance of historicizing our own emotional vocabularies. Moreover, they raise the importance of reflecting on changing ways of thinking – within history, literature, psychoanalysis – about emotions and their history. My desire, for example, to speculate on Pepys’ angry outburst bears a certain generic trace of psychoanalytic heritage: the repression of emotions that must find an outlet. Is this an appropriate, or a present-centred, reading of Pepys? Is it even possible to think ourselves out of our contingent historical ways of understanding emotions?

The diaries, in a more general way, also make us encounter the twin poles of the very activity of looking back historically: identification and alienation, sympathy and horror. I challenge anyone not to feel the pull of both of these when they encounter the following passage, at the Coronation in 1661:

But these gallants continued thus a great while, and I wondered to see how the ladies did tiple. At last I sent my wife and her bedfellow to bed, and Mr Hunt and I went in with Mr Thornbury…to his house; and there we drank the King’s health and nothing else, till one of the gentlemen fell down stark drunk and there lay speweing. And I went to my Lord’s pretty well. But no sooner a-bed with Mr Sheply but my head begun to turne and I to vomit, and if ever I was foxed it was now – which I cannot say yet, because I fell asleep and sleep till morning – only, when I waked I found myself wet with my spewing. Thus did the day end, with joy everywhere.

Rowan Boyson

King’s College, Cambridge

I’d like to highlight a different strand of the history of emotions, which concerns a surprising overlap between disparate insights from the history of science and studies of the aesthetic, which helped me think about the connection between emotion and epistemology. Around 2002, when I was beginning to plan a graduate research project, I read Lorraine Daston and Katy Park’s beautiful 1998 book Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150-1750.  Their inspiring introduction charts their shared curiosity on a scholarly journey that began with a more modest article on why ‘monsters’ featured regularly in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century science, blossoming out into a fuller history of the passion of ‘wonder’ itself. They quoted Francis Bacon in their Preface: ‘For all knowledge and wonder (which is the seed of knowledge) is an impression of pleasure in itself’. Their work joined and helped shape an agenda for rewriting the history of science not as a dispassionate pursuit of ‘truth’, but as one involving all kinds of emotions and affects – fear, attraction, pride, curiosity, pleasure… More recently Objectivity by Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison (2007) took the story through into the mid nineteenth century, showing how the concept of ‘objectivity’, the idea of scientist as ‘pure’, mechanical or non-emotional came historically into view.

Their inspiring introduction charts their shared curiosity on a scholarly journey that began with a more modest article on why ‘monsters’ featured regularly in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century science, blossoming out into a fuller history of the passion of ‘wonder’ itself. They quoted Francis Bacon in their Preface: ‘For all knowledge and wonder (which is the seed of knowledge) is an impression of pleasure in itself’. Their work joined and helped shape an agenda for rewriting the history of science not as a dispassionate pursuit of ‘truth’, but as one involving all kinds of emotions and affects – fear, attraction, pride, curiosity, pleasure… More recently Objectivity by Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison (2007) took the story through into the mid nineteenth century, showing how the concept of ‘objectivity’, the idea of scientist as ‘pure’, mechanical or non-emotional came historically into view.

At the same time as I was reading this kind of work in the history of science, there was a new agenda emerging in my home territory of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century literature, one which is often, though sometimes controversially, called ‘new formalism’ or ‘the return of the aesthetic’. Various books like Isobel Armstrong’s The Radical Aesthetic (2000), Peter de Bolla’s Art Matters (2003), and Simon Jarvis’s Wordsworth’s Philosophic Song (2007)  argued that the experience of art and poetry offered a kind of knowledge of its own. To put it in a very basic sense, a poem by Wordsworth does not contain a historical or philosophical meaning separate from the choice of words and its rhythm, nor are these things secondary or ‘merely’ pleasurable. Starting from this position also proposed a different kind of reading method, taking very seriously one’s emotional or subjective response to a literary work, against an earlier disciplinary orthodoxy where texts had to be dispassionately dissected for the way that they exemplified historical ideologies and structures of power. Much work in ‘new formalist’ vein has been influenced by Theodor Adorno’s brilliant disquisitions on the categorical and political distinctions and contradictions induced by modernity in Dialectic of Enlightenment and Aesthetic Theory. Though undoubtedly, in turn there will be many interesting and relevant critiques of this ‘new’ formalism, Adorno’s meditations on how categories like ‘emotion’ and ‘rationality’ are entangled are still incredibly compelling to anyone interested in the history of literature, in the history of science, and in the history of emotion.

argued that the experience of art and poetry offered a kind of knowledge of its own. To put it in a very basic sense, a poem by Wordsworth does not contain a historical or philosophical meaning separate from the choice of words and its rhythm, nor are these things secondary or ‘merely’ pleasurable. Starting from this position also proposed a different kind of reading method, taking very seriously one’s emotional or subjective response to a literary work, against an earlier disciplinary orthodoxy where texts had to be dispassionately dissected for the way that they exemplified historical ideologies and structures of power. Much work in ‘new formalist’ vein has been influenced by Theodor Adorno’s brilliant disquisitions on the categorical and political distinctions and contradictions induced by modernity in Dialectic of Enlightenment and Aesthetic Theory. Though undoubtedly, in turn there will be many interesting and relevant critiques of this ‘new’ formalism, Adorno’s meditations on how categories like ‘emotion’ and ‘rationality’ are entangled are still incredibly compelling to anyone interested in the history of literature, in the history of science, and in the history of emotion.

This week, I interviewed the philosopher and scientist Massimo Pigliucci as part of my research into philosophy clubs and the Skeptic movement. Massimo is a fascinating figure: he grew up in Italy, then moved to the University of Tennessee to become a professor in ecology and evolution, before moving to City University of New York to become a professor in philosophy. He began outreach work in 1997, in Tennessee, when he heard that local politicians were campaigning to re-introduce creationism into schools – he campaigned instead to introduce ‘Darwin Day’ into local schools. This led to him being approached by a Skeptic group called ‘The Fellowship of Reason’, who asked him to join.

This week, I interviewed the philosopher and scientist Massimo Pigliucci as part of my research into philosophy clubs and the Skeptic movement. Massimo is a fascinating figure: he grew up in Italy, then moved to the University of Tennessee to become a professor in ecology and evolution, before moving to City University of New York to become a professor in philosophy. He began outreach work in 1997, in Tennessee, when he heard that local politicians were campaigning to re-introduce creationism into schools – he campaigned instead to introduce ‘Darwin Day’ into local schools. This led to him being approached by a Skeptic group called ‘The Fellowship of Reason’, who asked him to join.

Chiara Beccalossi’s new book was developed from a PhD thesis at Queen Mary, University of London. The book is called

Chiara Beccalossi’s new book was developed from a PhD thesis at Queen Mary, University of London. The book is called