This essay is a personal opinion and may contain misunderstandings of my own. I’d be interested to hear from others with more knowledge and experience of ayahuasca, including indigenous healers or those who work closely with them.

This essay is a personal opinion and may contain misunderstandings of my own. I’d be interested to hear from others with more knowledge and experience of ayahuasca, including indigenous healers or those who work closely with them.

In the last 50 years, Western culture has imported many ecstatic practices. We lost our homegrown spirit as a consequence of a long process of disenchantment that began around the Reformation and continued through the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions. There were of course ecstatic revivals, like Romanticism, but they were counter-currents to the main tide.

Then, in the 1960s, there was a mass explosion of ecstatic practices. Part of that was fuelled by the rapid popularisation of non-western practices, such as yoga, Zen, TM, Tai Chi, Hari Krishna, Native American medicine like peyote and magic mushrooms, and also the popularisation of African-American culture like jazz, rock & roll and Pentecostalism.

But this ‘spiritual tourism’ raises some questions. What’s the right way to engage with another culture’s spiritual treasures? Do Westerners have the right to pick and mix, or to appropriate a culture (creating mindfulness, for example)? Can this sort of spiritual tourism actually be a form of cultural appropriation?

‘Cultural appropriation’ has become one of the rallying cries of left-wing identity politics in the US. It’s been defined as follows:

Taking intellectual property, traditional knowledge, cultural expressions, or artifacts from someone else’s culture without permission. This can include unauthorized use of another culture’s dance, dress, music, language, folklore, cuisine, traditional medicine, religious symbols, etc. It’s most likely to be harmful when the source community is a minority group that has been oppressed or exploited in other ways or when the object of appropriation is particularly sensitive, e.g. sacred objects.

Campus activists have, in the last few years, criticized things like white students dressing up as stereotypical Mexicans for parties, or the use of ethnic stereotypes for sports mascots, such as the Washington Redskins or the San Diego State Incas.

And the charge of cultural appropriation has also been levelled against whities adopting non-Western spiritual practices like yoga. In 2015, for example, the University of Ottawa cancelled a yoga class when students protested against it as an instance of cultural theft. This month, a professor at Michigan State University delighted the right-wing press by describing Westerners doing yoga as an instance of white supremacy and systemic racism.

The question of cultural sensitivity (or lack of) was levelled at my last book in an excellent review by Oxford PhD Maya Krishnan. She took issue with my exploration of tantra, saying I had failed to explore its intellectual history and merely presented the ‘neo-tantra’ of Osho, which is a valid criticism. She writes:

The importation and adaptation of experiences of ego loss does not have to be a problem if it is done in the right way. But is troubling to treat other cultures as experiential storehouses which can be raided for ‘good feels’, yet whose conceptual frameworks and intellectual contributions are not worthy of consideration. Engaging with non-Western traditions requires dismantling the hierarchy which allows non-Westerners to be adept at having feelings but which reserves the authority of interpretation for Western scientists and intellectuals.

Which brings me to ayahuasca tourism. Is this, also, an example of cultural appropriation? I read two books this week, both by anthropologists of ayahuasca, which presented starkly different views.

The first is a 2008 book called A Hallucinogenic Tea Laced With Controversy: Ayahuasca in the Amazon and the United States, by medical anthropologists Marlene Dobkin de Rios and Roger Rumrill. De Rios has been researching ayahuasca use in the Amazon since the 1960s, and she is appalled by the rise of ‘drug tourism’, ie plane-loads of Western seekers descending on Peru to swig ayahuasca in an attempt to get high and fill their spiritual emptiness.

The authors are against ayahuasca tourism for two reasons. Firstly, they condemn the rise of ‘charlatan’ neo-shamans, both Amazonian and gringo, who cater to the influx of drug tourists. They charge extortionate amounts to run ceremonies, they often haven’t the proper shamanic training and don’t know what they’re doing, they mix brews with all kinds of potentially dangerous plants in the mix (such as datura or deadly nightshade), and they sometimes seduce or assault their female western clients. They are a commodified corruption of the authentic, pure, traditional village shaman that de Rios encountered in the 1960s, whose practices existed unchanged for several thousand years before the gringo tourists turned up and ruined everything.

Secondly, the authors blame the other side of the market – the Western tourists. They exhibit a deep contempt for these tourists, in passages which are so intemperate, bilious and frankly weird as to be unacademic:

A number of upscale, well to do, prominent Americans and Europeans are touring Amazonian cities. Interested neither in parrots nor piranhas [?] , they revel in special all-night religious ceremonies presided over by a powerful shaman…Unlike the jungle denizens who for the last several thousand years have drunk the potion to see the vine’s mother spirit in order to protect themselves from enemies, to divine the future, or to heal their emotional and physical disorders, the urban tourist is a on a never-ending search for self-actualization and growth…Who are these spiritual seekers? They’re ‘narcissistic, selfish, permissive men and women who put their own selves first and foremost…There is the issue of out-and-out theft of the long-standing spiritual teachings and practices of others. Men and women select what they want and ignore anything that does not fit their model…They either have no respect, and treat ayahuasca as a party drug, or they exoticize the shaman into some sort of ‘happy savage’.

The phenomenon, write the authors, ‘has become so flagrant since the mid-1980s that the culture of native peoples is in danger of extinction’. And the worst of it is, it’s partly the fault of anthropologists like de Rios. They came back to the West with tales of marvellous psychedelic ceremonies, and did their best not to sensationalize their accounts, but this opened the floodgate to the goddam tourists: ‘such ‘mass’ or pseudo-intellectual people demand access to the drugs as if it were their natural right to do so.’ They’re not just risking their sanity, their arrival also ‘effectively destroys’ the purity of indigenous culture ‘that has roots in the prehistoric past’.

The authors raise two concerns. Firstly, vulnerable Western tourists are being exploited by fake shamans. Secondly, rapacious Western tourists are ruining indigenous culture with their ravenous, disruptive and ignorant spiritual consumerism. You could say, well, both sides are exploiting the other in a free exchange, is that such a problem? Yes, says de Rios, because it’s destroying the authentic indigenous shamanism which she – the expert anthropologist – uniquely appreciates.

The second book I read is called Ayahuasca Shamanism in the Amazon and Beyond, and is a collection of essays by anthropologists, published in 2014. I think it’s a much better book than the first, because it maintains a critical distance all too often lacking from academic explorations of ayahuasca. Academics have tended to get lost in their own trip: ayahuasca is an encounter with the secret of DNA (Jeremy Narby), or with ‘Grandmother Ayahuasca’ (Rachel Harris). Such personal accounts make for compelling reading, but they lack critical distance.

The second book I read is called Ayahuasca Shamanism in the Amazon and Beyond, and is a collection of essays by anthropologists, published in 2014. I think it’s a much better book than the first, because it maintains a critical distance all too often lacking from academic explorations of ayahuasca. Academics have tended to get lost in their own trip: ayahuasca is an encounter with the secret of DNA (Jeremy Narby), or with ‘Grandmother Ayahuasca’ (Rachel Harris). Such personal accounts make for compelling reading, but they lack critical distance.

The book begins by suggesting the contemporary phenomenon of ayahuasca use by Amazonians and Westerners has been ‘poorly served’ by anthropologists in the past, because they’ve constructed naive and ideologically-loaded theories of a pure and authentic traditional culture which existed unchanged for millennia until it was suddenly destroyed by Western tourists. Instead, the editors write:

Local shamanism, cosmopolitan biomedicine and psychology, alternative therapies, New Age spirituality, and the tourism service industry have blended in intricate and fascinating ways that challenge traditional ethnographic notions of authenticity, ethnicity, tradition and place.

Firstly, is ayahuasca use among Amazon Indians definitely pre-historic? Recent work by Peter Gow, Bernd Brabec de Mori and other anthropologists challenges this view, pointing out that there’s no evidence for ayahuasca use among Amazon tribes before the 19th century. There’s evidence for the ingestion of DMT going back to prehistoric times, but not for the use of the ayahuasca brew, which mixes the ayahuasca vine with the chacruna plant. We don’t know how or when this mixture was discovered, but these authors suggest knowledge of the mixture spread among Amazon tribes in the mid-19th century as a consequence of the disruption of the rubber boom and the rise of Jesuit missionary camps, or reducciones, established by Jesuit missionaries from the 17th century onwards.

Stephan Beyer writes:

Indigenous people sought the protection of these camps from epidemic disease, depopulation, slave raiders, and the military threats of their neighbours. Here they were forced to live in common compounds regardless of their tribal distinctions. The intention was that in this way the indios infieles could be more easily controlled and converted to indios cristianos; but the unintended consequence was to form a pressure cooker of cultural interchange.

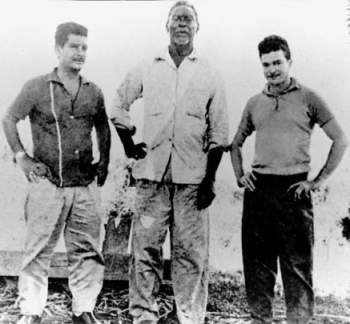

Irineu Serra with the Costa brothers

Some tribes have only started using ayahuasca in the last few decades, and have embraced it with enthusiasm. A handful of white settlers seem to have drunk ayahuasca since at least the 1920s – the founder of the Santo Daime ayahuasca church, an Afro-Brazilian called Raimundo Irineu Serra, was introduced to ayahuasca by two Spanish-Brazilian brothers, Antonio and Andre Costa. I read on the Santo Daime website that: ‘At this time the sacrament was used to guide the Indians in hunting and fishing, and also to entertain the white man in the moonlight.’ Ah the white man, always seeking entertainment.

In other words, the history of ayahuasca may be quite recent, and from the start seems to be deeply intertwined with the history of globalization, empire, disruption, trade, research and tourism. There may not be an indigenous ayahuasca culture which existed pure and unchanged for millennia before it was ruined by foreigners. On the contrary, it may have arisen quite recently, out of the shock of change and the encounter with different tribes and western civilization, and then spread through new technologies and new exchanges of knowledge and trade, including the internet. I think ecstatic practices often arise in this way, out of the shock of economic and political change and the violent / creative encounter between tribes and cultures.

Secondly, what is the ‘authentic’ use of ayahuasca, who owns it, who is entitled to use it, and how? Glenn Shepard notes that some tribes like the Yora have only started using ayahuasca since the 1980s, and asks:

Is there anything special, unique or particular about indigenous people’s relationship to ayahuasca when compared to adepts who use it in urban centres? Do the Matsigenka and Yora have an inherently superior moral right to consume ayahuasca within their spiritual tradition when compared with, say, a Belgian Santo Daime member risking incarceration to consume an illegal substance? Such questions raise troubling doubts about our sometimes facile resort to terms such as ‘tradition’, ‘modernity’ ‘indigeneity’, and ‘authenticity’.

There are genuine issues around the economics of ayahuasca tourism. On the one hand, why shouldn’t local ayahuasqueros make money from their work? Why shouldn’t tourism revenues go into the Uyacali, one of the most deprived regions of Peru? On the other hand, Bernd Brabec de Mori estimates that only a few dozen Shipibos ‘live well on ayahuasca tourism’ out of a population of 50,000. Centres owned by or employing Westerners have advantages of language and culture which enable them to attract more Western tourists than local healers. The inequality caused by tourist revenues leads to envy, social discord, and magical attacks against shamans who cater to gringos. And it can mean that locals are priced out of the market – why would shamans provide their services to locals for free when you can sell them to gringos for hundreds of dollars?

There are also serious issues with the ethics and competence of shamans – boom times always lead to a rise in shysters. But I’m sure there have always been shamans who caused harm and abused their power, as with priests, therapists, gurus, psychiatrists or any technicians of the soul. Western tourists should be aware of this and not romanticize or exoticize the shaman, which is forgivable and well-intentioned but still a subtle form of objectification. Daniela Peluso writes:

whereas Amazonian women tend to view shamans as humans who can potentially be abusive, uninfomred Western women do not…it is the coinciding of shamans who view women as easy prey with women who idealize shamans that exacerbates the trend of seduction within ritual contexts.

Has a ‘pure’ indigenous shamanism been corrupted by foreign influence? Yes, some ‘neo-shamans’ offer rituals which seem to throw everything into the mix – jaguars, condors, Mama Ayahuasca, Pachamama, Jesus, Mary, chakras, spiritualism, energy fields, past lives, UFOs. And you could see that as a corruption caused by the similarly ‘pick n’ mix’ Western tourists. But to me, Latin American folk religion has been that sort of syncretistic mash-up for several centuries.

It’s hard for a Western academic to decide which shamans are legitimate and which are bogus, because it depends on unquantifiable things like their dominion over the spirit world. It’s also arrogant and even imperialist – who is de Rios to decree who are genuine shamans and what is and isn’t the legitimate use of ayahuasca? Who made her the jungle pope?

Are Western tourists so very decadent in their motives? Evgenia Foutou met and interviewed many ayahuasca tourists in Peru, and discovered: ‘A majority of participants in ayahuasca ceremonies are motivated by a desire to be healed and have reported successful healing from both psychological and physical ailments.’ That’s not so different to Amazonian clients. Are they more disrespectful in their approach to rituals? No – if anything, they’re more pious. Shipibo ceremonies for tourists are, according to Brabec de Mori, far more formal than ceremonies for locals, in which the shaman will rarely dress up and people come and go as they please. Shipibo shamans joke among themselves, apparently, about the ridiculously elaborate shows their peers put on for the tourists.

Diverging models of illness and healing

There is, of course, a world of difference between Western and Amazonian theories of psychological illness and cure. As Anne-Marie Losonczy and Silvia Mesturini Cappo explore in their essay on ‘Ritualized Misunderstandings’, Amazonians see illnesses either as natural (and therefore treatable with biomedicine) or as caused by sorcery. Ayahuasca helps the shaman identify the instigators of the sorcery, battle the malevolent spirits they have sent, and sometimes get revenge. The cause and cure for illness are ‘out there’, in present social disputes.

Westerners by contrast see psychological problems as caused by emotions, often rooted in family relationships and childhood traumas, and think healing involves release, acceptance, love, forgiveness and sometimes an encounter with one’s higher self or a benevolent higher power, rather than some local and morally-ambiguous spirit ally. The cause and cure for illness are ‘in here’, often in the past.

In other words, the Amazon shaman and the Western tourist meet in the incredible intensity of the ayahuasca ceremony, and have completely different models of what takes place. There is a ‘fundamental misunderstanding’. But they both come away satisfied. They’re able to do this partly because the ceremony takes place in music and gesture, while verbal interaction is kept to a minimum. Western or local mediators help to translate what’s taking place into terms the Western clients can accept, like ‘facing your shadow’ or ‘discovering the real you’.

I chose to do ayahuasca at the Temple of the Way of Light, a well-known centre near Iquitos set up by a British man, which employs Shipibo shamans, because it combined indigenous practitioners with Western facilitators. I wanted to be able to seek support from Western therapists if necessary. My understanding of what was taking place was guided by them, more than the shamans, who didn’t speak English. I did find the shamans’ singing extraordinary and important to my healing experience, but who is to say how much of that was cultural projection on my part? I simply don’t know, because I don’t know whether ayahuasca connects to a genuine spirit world, and what the nature of that world is. I don’t know the precise distribution of revenues within the Temple, but it does fund an institute to support local indigenous communities and culture, and also to support the sustainable growth of the ayahuasca vine.

To conclude, ayahuasca tourism involves all kinds of risks, myths, misunderstandings and unintended consequences. As tourists we should seek to protect ourselves from the risks, and be careful who we trust. It might also be respectful to research about indigenous ayahuasca culture, which is what I’ve done since coming back from Peru. But the more I do, the more I see the distance between Western understandings of ayahuasca healing, and Amazonian understanding of it. Most Western tourists are ignorant of the sorcery-model of illness and healing, and I think would be quite surprised and put off if they knew more about it. To me, it is not a good model for Westerners, not one I want to adopt or disseminate.

What we see in ayahuasca tourism, instead, is a Westernized, Christianized version of ayahuasca culture. Instead of the Amazonian idea of dominating spirits in order to expose your secret enemies and get revenge, Westerners use ayahuasca to identify the traumas or emotional blocks in their psyche, and to find healing through acceptance, love, perseverance, and surrender to a totally benevolent higher power. It’s close to the therapeutic Deism one finds in most contemporary churches, in which Jesus is basically your life coach, but with a nature Goddess rather than a cosmic God. Perhaps it’s rather boring and bland compared to Amazonian sorcery battles. But I think it’s much healthier for Western psyches.

If ayahuasca use continues to grow among Westerners, we’re likely to see more and more Westernized centres, owned and run by Westerners, probably increasingly based in Europe and the US (in Oregon, a new church which uses ayahuasca is currently defending its right to use the brew in the courts). Where will they source their ayahuasca? Do we have the right to grow our own ayahuasca and use it for our own rituals (as Santo Daime has done)? Will that leave indigenous healers out entirely? Is that a bad thing, or should each culture stick to its own culture?

One thing I’m certain of is that no one is really in charge, no one is in control, and a variety of different forms of ayahuasca culture will emerge, from religious cults to DIY secular libertarianism. Who knows which will flourish and spread. Maybe the medicine knows!

Now here is the key point I want to emphasise. As more and more people meditate and take psychedelics, more and more people are also reporting spiritual or mystical experiences (see the results from Gallup on the right). And some of those experiences will be quasi-psychotic spiritual crises.

Now here is the key point I want to emphasise. As more and more people meditate and take psychedelics, more and more people are also reporting spiritual or mystical experiences (see the results from Gallup on the right). And some of those experiences will be quasi-psychotic spiritual crises.